This blog post reports on work-in-progress within the DfG course! The post is written by group 1A dealing with Metsähallitus and the Ministry of the environment’s brief on Sustainable nature recreation. The group includes Radhika Motani from the Creative Sustainability program, Ulrika Ura from the International Design Business Management program, Zita Tedjokusumo from the Creative Sustainability program, and Marleena Halonen from the Creative Sustainability program.

Written by: Radhika Motani

This blog shares our process of identifying, defining, and justifying our problem area which would lead the way to switch our thinking hats to the solution space. During the last phase, we had to consciously try and avoid stepping into the research analysis that arises from a solutionist point of view. This helped us avoid our own basis towards the topic and uncover some unexpected and underlying problems that allowed us to constantly reiterate the importance of focusing on the non-human perspective, which is biodiversity in our case. Here we will uncover the challenges and methods used to prioritize a problem area that would be valuable to our human as well as non-human stakeholders.

Listening to biodiversity

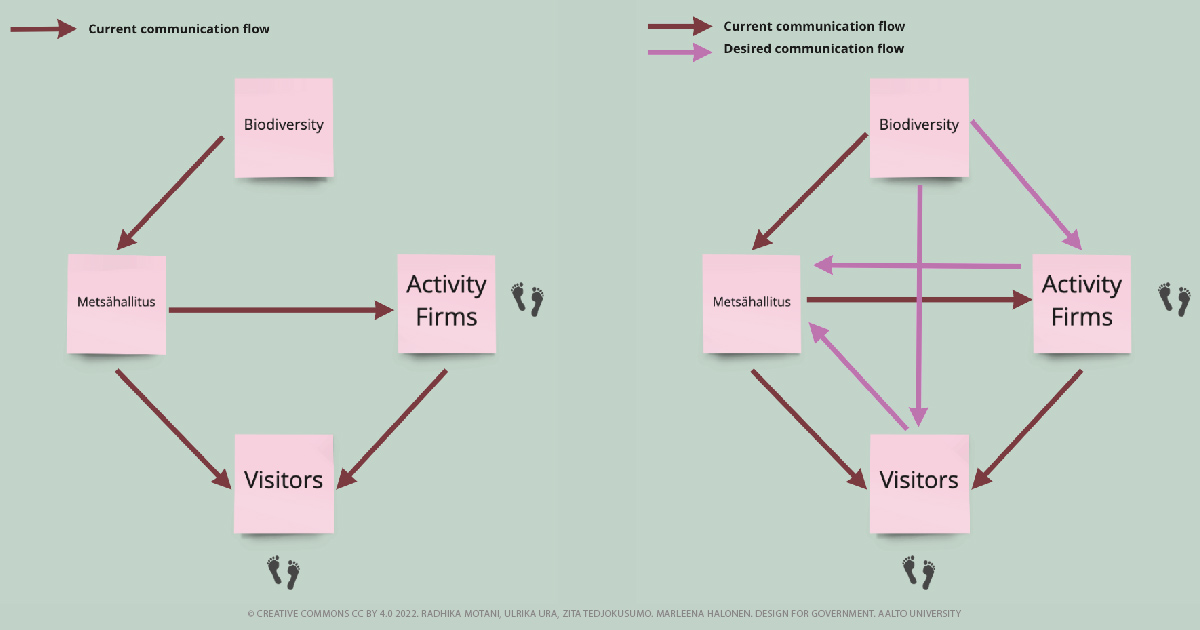

Since our mid-term presentation, the aim was to identify the gaps that currently exist in the communication flow between our stakeholders in understanding biodiversity needs. One of the key learning that helped frame our starting point was that currently biodiversity is bearing the impact of visitor footprint but the dialogue from biodiversity is missing. This is also a key challenge since we are working with a stakeholder that cannot speak for itself but can be listened to. Only Metsähallitus is equipped with the resources and tools to listen to the needs of biodiversity directly by utilizing the knowledge from experts. The visitors and activity firms are currently at the receiving end of the dialogue between biodiversity and Metsähallitus in this complex game of Chinese whisper.

Figure 1: Communication flow about biodiversity needs.

Mapping the leverage points

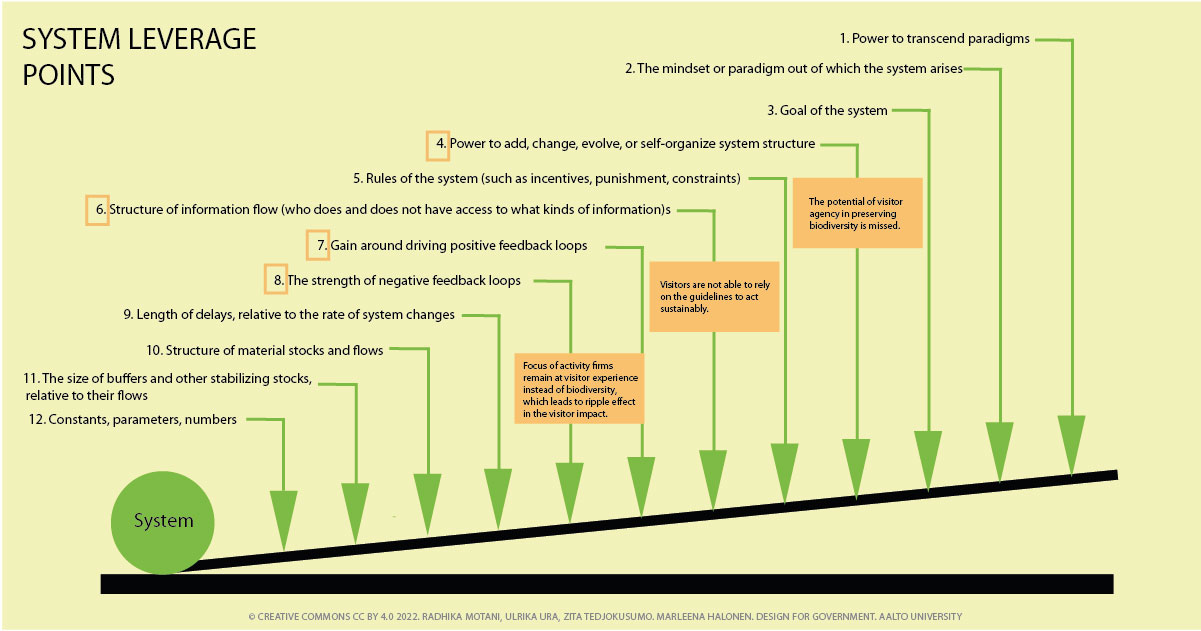

The Leverage Points by Donella Meadows (Meadows, 1999) was a helpful tool in discussing and identifying the places to intervene in the system. We mapped our core problem areas into the different leverage points to realize that the solution space could lean towards interventions at the strategic levels by influencing the goals of the system and also at lower leverage points by altering the feedback loops that currently exist. Through this process, we were questing if a higher leverage point always results in a greater impact in the system, and this helped us understand the importance of limitations and boundaries that must be considered before making these choices. For example, we would have to consider criteria such as the resources and the ability that Metsähallitus can leverage to catalyze the change.

Figure 2: Problem areas mapped to the leverage points by Donella Meadows.

Untangling the roots

We started to define the pros and cons of each problem area to acknowledge how interconnected each of them is to each other. For example, a visitor would be able to realize the potential of the agency only if the visitor is educated about biodiversity needs.

One of the findings that re-surfaced through an interview with Kaisa Junninen (Specialist in recreative) was the concern towards rocketing biodiversity impact because of the increase in the visitor footprint in relation to the size of Nuuksio. This helped us re-iterate the importance of finding ways to translate the negative impacts of visitors on biodiversity into positive through the potential of visitor agency.

We used a storytelling scenario to define the exact problem or situation that we want to change and imagined what an ideal scenario would look like to help us start thinking about the design intervention. Our story is communicated through Mona (a regular visitor of Nuuksio) who notices visitor actions that could be harmful to biodiversity in Nuuksio. For example, loud music that could disturb the animals living there, or trash left by other visitors. She wants to act upon it and share some ideas with Metsähallitus but is not sure of the means to do so. She is able to locate the feedback page with some difficulty on Metsahallitus’s website but sees no point in it this time since her suggestions had not been addressed previously.

In the ideal scenario, Mona would be encouraged by Metsähallitus to be more than just a visitor of Nuuksio. She would have the means to be heard and participate in activities that co-generate ideas along with experts on biodiversity preservation.

This process of framing the problem area helped us understand that there are informed groups of visitors who understand the value of the national parks and try their best to take ownership of their own actions towards mitigating biodiversity impact. But the current system prevents the stakeholders in power (Metsähallitus) from acknowledging the value that the visitors can bring to the table, since the visitors are the ones who best understand the reasons for certain behaviors in the national parks. For example, when we visited Nuuksio, we were forced to walk off track because the marked trails were too slippery. So how can Metsähallitus leverage the power that the visitors can have in contributing to improvements towards biodiversity needs rather than playing the blame game? This led us to think about our design intervention in a manner that positively utilizes the local knowledge that the visitors hold and de-centralizing the power in decision making. Because ultimately, no one wants to purposely behave unsustainably, it may just be a matter of circumstance, misunderstanding and communication.

Our thoughts were backed by examples of best practices in different parts of the world on interventions where citizen participation has been key in sharing diverse perspectives on biodiversity preservation. The key learning here was the importance of suggestions based on ground-level experiences of the visitors in relation to biodiversity impact rather than top-down initiatives from stakeholders that do not necessarily interact with biodiversity on a regular basis.

Next Steps

Moving forward, we will study the different levels of citizen participation that would help us evaluate the value of the proposed design intervention. We will soon enter the ideation phase to identify instruments and tangible ways to increase citizen participation in decision-making towards biodiversity preservation. We also have interviews lined up with our stakeholders to get feedback on our potential design intervention and validate the viability of the intervention with the existing resources and influence that they have.

The DfG course runs for 14 weeks each spring – the 2022 course has now started and runs from 28 Feb to 23 May. It’s an advanced studio course in which students work in multidisciplinary teams to address project briefs commissioned by governmental ministries in Finland. The course proceeds through the spring as a series of teaching modules in which various research and design methods are applied to address the project briefs. Blog posts are written by student groups, in which they share news, experiences and insights from within the course activities and their project development. More information here about the DfG 2022 project briefs. Hold the date for the public online finale online 09:00-12:00 AM (EEST) on Monday 23 May!