This blog post reports on work-in-progress within the DfG course! The post is written by group 2C dealing with the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health’s brief on Continuity of Care as a new Kela reimbursement.

The group includes Sofia Pascolo and Devayani Mohanraj from the Master’s Programme in Creative Sustainability, Heidi Mäkitalo from the Masters Programme in Computer, Communication, and Information Sciences program (Human-Computer Interaction Major), and Robert Hartmann from the Master’s Programme in Collaborative and Industrial Design

Written by: Robert Hartmann

Let’s say it right at the beginning: We didn’t manage to narrow down the concept of continuity of care. Instead, our ongoing research has prompted a deeper exploration of choice, prevention, and personal health engagement. From the desk research in the beginning, more concrete research streams have emerged to examine the different layers of the Finnish healthcare system. We approach continuity on the administrative level, from the doctor’s – respectively the patient’s perspective. Our group focused on the patient’s perspective. As I am writing this blog post, we presented our findings and possible opportunities to our project partners and received feedback for the second half of the project.

Speed vs. Continuity

At the beginning of this project, I saw the lack of continuity of care within the Finnish healthcare system as the mere incapacity of the system to create connections between doctors and patients. In the attempt to generate rapid access to healthcare, for example with the Health Act in 2010, the system has hollowed itself out, sacrificing continuity for speed. This reduction in continuity made consultations less efficient and increased the need for specialized care, which is again accessed through primary care (GPs); and here we are, in a slow system without continuity. We would, therefore, need to restore the state of the Finnish healthcare system of the 1980s, a moment when the system was both accessible and continuous (Eskola et al., 2022).

With our group’s focus on the patient scale of continuity of care and 6 patient–interviews later, my opinion has evolved by a fair bit: Not only the system but the society has changed. The Healthcare system and its’ users are in a strong interdependency: People navigate in the system the way they do because the system is the way it is – and the system is the way it is due to how people navigate in it. This dynamic gives us two axes for improving continuity but also obliges us to reflect on how healthcare might blend into our future customs.

The Importance of Choice

The extensive possibility of choice is a particularity of Finnish healthcare.

While double-class systems, of private and public healthcare, exist in many European countries (OECD & European Union, 2020) occupational healthcare in Finland provides additional private services to a far greater part of society. With one-third of society (approx. 2 M.) benefitting from comprehensive health packages, the additional coverage enables users to choose between their registered public health center and private services (Turunen. 2020).

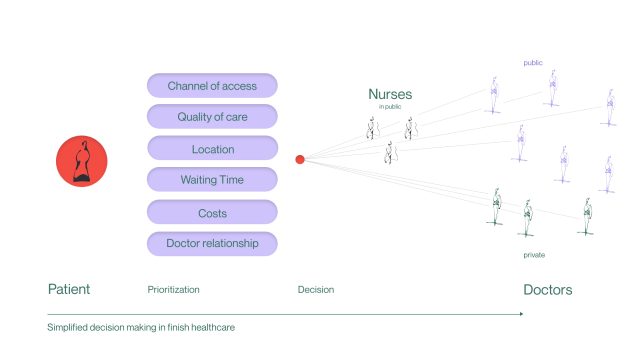

Choice in healthcare is a two-folded concept: On the one hand, it is associated with increased compliance with the treatment, greater patient- satisfaction, and empowerment of patients to manage their health (Saltman, 1994). On the other side, choice also means that some patients might prioritize other factors than a continuous doctor-patient relationship. Our interviews confirmed this “risk”: Only old respondents or those who had a severe chronic condition were willing to sacrifice waiting time or a long distance to have a closer doctor relationship. I present the decision process and choice-relevant factors presented in the scheme below.

So, we need to weigh the benefits of continuity, like lower mortality rates (Eskola et al., 2022), against the value of being able to choose healthcare options.

Decision factors which are considered differently by diverse patient groups and dependent on their condition. (by author) (Channel of access: e.g callback system/website; Doctor relationship: Seeing the same doctor over an extended period) © CREATIVE COMMONS CC BY 4.0 2024. Sofia Pascolo, Devayani Mohanraj, Heidi Mäkitalo and Robert Hartmann DESIGN FOR GOVERNMENT. AALTO UNIVERSITY

Younger, healthy patients seem to care less about continuity of care. (Picture taken during a Patient interview (by author))© CREATIVE COMMONS CC BY 4.0 2024. Sofia Pascolo, Devayani Mohanraj, Heidi Mäkitalo and Robert Hartmann DESIGN FOR GOVERNMENT. AALTO UNIVERSITY

Patient vs. Customer

One of our interview partners, who made use of both private and public services in the past, introduced the comparison between customer and patient in the Finnish healthcare system. According to him, “patients” describe trusting users who accept their limited knowledge and agree to start consultation with nurses. “Customers” ask for GPs – or specialized doctors right away, in a self-perception that they know what they need. In the private sector, they receive the demanded service at a speed that can only be realized with large buffer capacities (doctors that have open appointments). While direct access to the GPs can lead to a faster diagnosis, many of the treatments that would be realized by nurses in the public sector use the precious capacity of GPs in the private. Furthermore, our interviewee mentioned that nurses in the public sector often appeal to patients’ autonomy compared to the private sector where they receive “health as a product”. This brings us to a more general reflection about the ownership we are willing to take for our health. During the mid-term presentation, the county’s Chief

Administrative Physician, Veli-Pekka Puurunen (2024), pointed out that the underlying reasons patients initially visit general practitioners are often beyond the doctor’s control. Continuity of care has to extend to other areas of life and connect to our customs, lifestyles, and mindset.

Outlook for the second half

For the remaining half of this project, we want to find the overlap between the advantages of continuity of care (a longer doctor-patient relationship) and the advantages of freedom of choice. We must consider bigger societal streams regarding health and their impact on decision-making on the smallest scale. Only then can we get people back – in the driver’s seat of their health.

References

Eskola, P., Tuompo, W., Riekki, M., Timonen, M., Auvinen, J.(2022). Hoidon jatkuvuusmalli : Omalääkäri 2.0 -selvityksen loppuraportti. Sosiaalija terveysministeriö. https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/handle/10024/164291

OECD & European Union. (2020). Health at a Glance: Europe 2020: State of Health in the EU Cycle. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/82129230–en

Puurunen Veli-Pekka. (2024, April 10). MID-Term presentation DfG [Personal communication].

Saltman, R. B. (1994). Patient choice and patient empowerment in Northern European health systems: A conceptual framework. International Journal of Health Services, 24(2), 201-229. Baywood Publishing Co., Inc.

Turunen Jarno (2020 ) Funding and costs of occupational health care | Work-life knowledge service | www.worklifedata.fi. Retrieved April 12, 2024, from https://www.worklifedata.fi/en/analysis/analysisOhsCosts

The DfG course runs for 14 weeks each spring – the 2024 course has now started and runs from 26 Feb to 29 May. It’s an advanced studio course in which students work in multidisciplinary teams to address project briefs commissioned by governmental ministries in Finland. The course proceeds through the spring as a series of teaching modules in which various research and design methods are applied to address the project briefs. Blog posts are written by student groups, in which they share news, experiences and insights from within the course activities and their project development. More information here about the DfG 2024 project briefs. Hold the date for the public finale on Wednesday 29 May!