This is the second blog from group 2C. We are working with the brief from the Ministry of Finance on the TE2024 reform model, focusing on the international jobseeker’s perspective. Our group includes Mark Laukkanen from Information Networks program, Mathias Leopold Hörlesberger from New Media Design and Production program, Sera Remes from Collaborative and Industrial Design program, and Sanne van der Linden from Creative Sustainability program at Aalto University.

Written by: Sanne van der Linden

Since the last blog post, we have been working on gathering as many insights as possible from the different stakeholders in our project. These stakeholders include employees from Kela and TE offices, who are working directly with the customers, as well the international jobseekers who make use of the employment services. Altogether, we conducted 14 interviews, 8 with public servants and 6 with international jobseekers. With these interviews and their analysis we have been able to get an understanding of the problems and relations within the system of the employment services.

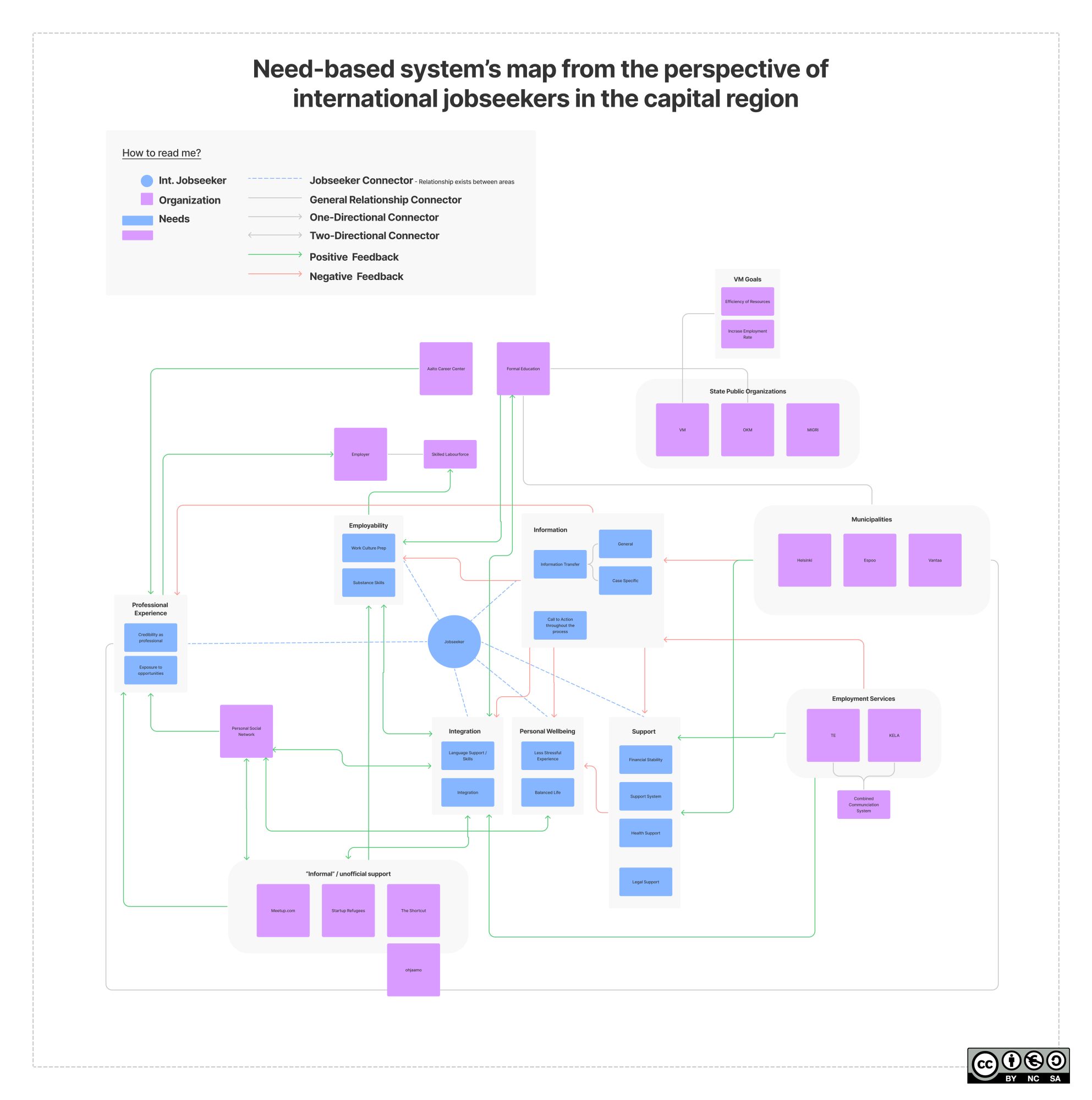

The main goal of these last few weeks has been to make sense of all the interview data that we gathered. For this, we have used different mapping tools to help us structure all the information. The interviews with TE and Kela employees have helped us in understanding how these organizations work together, and when and how they interact with the jobseekers. The tool that we used to visualise this is the systems map. A systems map is a visual map that shows the relations between the different stakeholders and elements of a certain event or service. This tool is useful for creating overview and visualising what parts of a service you are looking at. In our case, we placed the jobseeker in the middle of the map and drew connections to the different stakeholders that are relevant in the employment services, which can be seen in figure 1. In doing so, we realized that the relations between the jobseeker and the organizations and service elements are linked through the needs of the jobseeker. For example, the need for clear information and the need for support with integration. We struggled with how these relations with the needs can be defined in a systems map in terms of feedback (negative or positive), and therefore decided to focus more on the journey of the jobseeker rather than spend too much time on the systems map.

Figure 1. Need-based systems map from the international jobseekers’ perspective, © Sanne van der Linden.

Because the journey from becoming unemployed to hopefully finding a new job is one full of uncertainties, information plays a key role. Information is important to give the jobseeker a sense of control. With clear information, the jobseeker is given an overview of their process, they know what to expect and what is expected of them, and they know where to look for information. Basically, they feel supported on multiple levels. These ‘levels of support’ is a concept that we derived from our insights. We defined three different levels, that relate back to different types of information, and to different touchpoints and elements of the employment services. The three levels provide support on:

- Using the system and services

- General job preparation and integration

- Job seeking in specific personal line of work

We can use these levels of support later on in our project to define which type of information and support we are referring to. Additionally, these levels can be used to evaluate possible solutions as we can make the levels differ in importance.

When looking at the international jobseeker, we can see that the need for the three different levels of support is closely related to how well their other needs are being met. With these needs, I mean the ones that we identified in our systems map (see figure 1). If a jobseeker has a very solid support system here in Finland, they might not need support on how to use the Finnish systems. If they have a Finnish partner, they might not need so much support on integration into the Finnish culture. But just imagine coming to Finland without any prior knowledge of the Finnish system, with a small or even non-existing social network (support system), and without speaking the language. Whenever an international jobseeker encounters any unclear information, such as lack of progress updates, lack of call to action for next steps and information provided in Finnish or weirdly translated to English, the impact this has on how they proceed is much more significant than it would be for a native Finnish person who is familiar with the systems.

Our process of the last few weeks has been intense but rewarding. It takes some time to wrap your head around all the information that you have gathered, and then to make some sense out of it. If you would be able to look at our working boards, you would find a beautiful chaos of many different types of mapping and attempts to structure the data. Although this requires a lot of thinking, transforming, and then letting go again, it is also a part of the design process I enjoy a lot. After our mid-term presentation however, I did realize that we might have been immersed in our own bubble a little bit too much. Some stakeholders pointed out that the information issues we had been discussing might also be experienced from the other side of the coin, or the employees providing the information. Personally, I think this is because we mainly focussed on the journey of the jobseekers and used the interviews with the employees to understand the system. If we would have been able to use the interviews with TE/Kela employees for the journeys as well, we might have gained more insights into the other side of the information issues.

As we are talking about expectation management in terms of providing the jobseekers with the right information, the employees should also be able to give that information. So, to use the phrasing of a stakeholder, these ‘information traps’ are relevant for both sides of the service touchpoints. As an employee, to be able to support a client in the best way possible, you should be supported as well in doing so. I think this is an interesting perspective that we should take with us for the next phase. We should be looking at how the needs of jobseekers can be met in the best possible way, but also at how the service providers can be supported so that they have the ability to do so.

The DfG course runs for 14 weeks each spring – the 2022 course has now started and runs from 28 Feb to 23 May. It’s an advanced studio course in which students work in multidisciplinary teams to address project briefs commissioned by governmental ministries in Finland. The course proceeds through the spring as a series of teaching modules in which various research and design methods are applied to address the project briefs. Blog posts are written by student groups, in which they share news, experiences and insights from within the course activities and their project development. More information here about the DfG 2022 project briefs. Hold the date for the public online finale online 09:00-12:00 AM (EEST) on Monday 23 May!