This blog post reports on work-in-progress within the DfG course! The post is written by group 1C dealing with the Prime Minister’s Office and Ministry of Environment’s brief on ‘Mainstreaming Biodiversity’. The group includes Dinah Coops and Anna Halvorsen from Creative Sustainability program, Sari Kukkasniemi from Collaborative and Industrial Design program, and Thao Nguyen from International Design Business Management program.

Written by: Sari Kukkasniemi

What Is Your Definition of Biodiversity?

According to the University of Helsinki (2023), problems in communication are one of the most serious problems in the world. For example, do the participants in a meeting understand the concept of biodiversity in a similar way? How many different interpretations do the government employees have about EU Biodiversity Strategy? How do these differences affect the various levels of policy-making and implementation?

Figure 1. The importance of mutual understanding is not something to ignore.

With these thoughts in mind, we have been getting to know the context of our project brief Mainstreaming Biodiversity, as well as our partners from Prime Minister’s Office and Ministry of Environment during the first three weeks of the Design for Government course. The question posed in the subheading was the same we asked our partners to answer in the roundtable discussion as a thought-provoker — and it did stir thoughts for all of us. Biodiversity might be understood differently across ministries but, also, inside the departments and units of the Ministry of Environment. Given this insight, how can the Prime Minister’s Office facilitate a coherent government policy model for biodiversity?

The Horribly Complex, Yet Fundamental Dark Matter

Communication, as crucial it is, is only one of the many interdependent elements in a dynamic system. During the roundtable we discussed that to get everyone on board for policy coherence, it may be crucial to have the concept of biodiversity to suit each actor’s context, motivations, and goals. Based on our research so far, we know that the root causes of nature loss are nothing less than societal values and behaviours (IPBES, 2019). These intangible factors related to human behaviour makes “things go nonlinear,” to quote Neil deGrasse Tyson (2016).

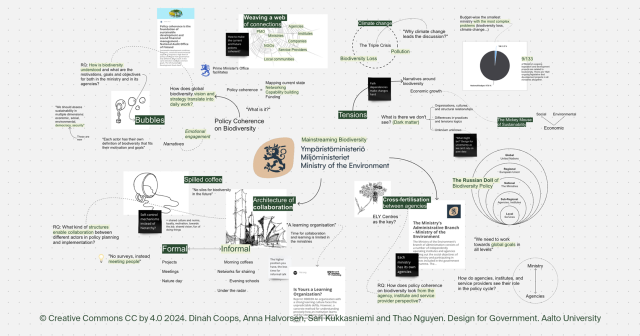

Indeed, the complexity of the system has started to uncover with the manifestations of dark matter. Originally introduced by Wouter Vanstiphout, the notion suggests that organisations, culture, and structural relationships are binded together as sort of complex, formless material (Hill, 2012). Public services and even policies themselves are outcomes of the organisational cultures, path dependencies, institutions, or values of their time. During the first weeks we have zoomed in and out, dove into background materials provided by our partners, and defined our research questions around these complex instances of dark matter.

Figure 2. Trying to wrap our heads around the various instances of dark matter with a mind map of the first few weeks in Miro. Phew!

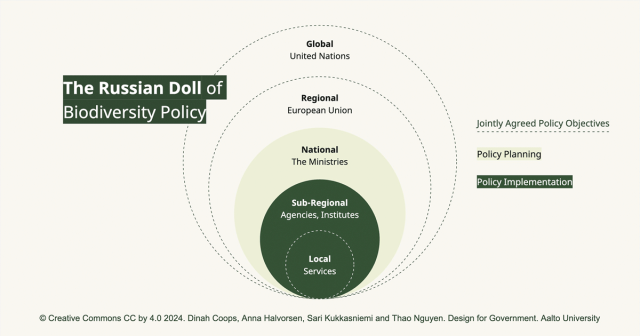

The Russian Doll

The focus of our group is the vertical dimension of policy coherence – the agencies, institutes, and other service provisioning entities under the Ministry of Environment’s administration. In practice this means that we will be exploring opportunities for policy implementation by building cross-cutting linkages between the Ministry of Environment and its agencies, as well as seeking leverage points for cross-agency collaboration. Nevertheless, understanding the bigger picture of policy coherence is needed.

Framed by Marco Steinberg during one of the early lectures, the policy system can be thought of as a Russian Doll of sorts. We think of this as a useful metaphor because of two insights we have had so far. Firstly, the Russian Doll is a complex system consisting of nested layers, each containing its own unique properties, dynamics, and scale. Secondly, the Russian Doll is prone to the concept of a broken phone — meaning that the high-level vision and strategy may dilute and change from the original the inwards you go.

Figure 2. The Russian Doll metaphor helps us think on different scales.

As Peter Shergold argues, good policy should harness the views of those likely to be impacted by the proposal (2015). Focusing on the lived experiences of the employees of the ministry (i.e. policy planning) and the civil servants of government agencies, institutes, and service providers (i.e. policy implementation) we can increase the likelihood that policy coherence will succeed. In other words, the grassroot perspective of the system matters.

The Architecture of Collaboration

Cross-fertilisation

Noun

interaction or interchange, as between two or more cultures, fields of activity or knowledge, or the like, that is mutually beneficial and productive (Dictionary, 2024).

To continue with metaphors, we are seeking to understand how cross-fertilisation could be facilitated in all levels of public administration. What kind of architectures of collaboration are there in place? Are there differences in practices? How about tensions between institutional logics? Fortunately, design encourages the transcendence of organisational and procedural silos, established hierarchies, and bureaucratic categories (Mintrom & Luetjens, 2016). The next steps will be towards human perspective through field research with the different governmental agencies, institutes, and service providers as well as with our partners from the Ministry of Environment and Prime Minister’s Office. Onwards, to the depths of the system!

References

Dictionary.com. (2024). Cross-fertilization.

Hill, D. (2012). Dark Matter and Trojan Horses: A Strategic Design Vocabulary, Strelka Press.

IPBES. (2019). Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany.

Mintrom, M. & Luetjens, J. (2016). Design Thinking in Policymaking Processes: Opportunities and Challenges. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 75:3, 391-402.

Shergold, P. (2015). Learning from Failure: Why Large Government Policy Initiatives Have Gone So Badly Wrong in the Past and How the Chances of Success in the Future Can be Improved. Canberra: Australian Public Service Commission.

University of Helsinki. (2023). Research group Mutual Understanding. https://www.helsinki.fi/en/researchgroups/mutual-understanding/about

Tyson, deGrasse Neil. (2016). In science, when human behavior enters the equation, things go nonlinear. That’s why Physics is easy and Sociology is hard. https://twitter.com/neiltyson/status/695759776752496640?lang=en#

The DfG course runs for 14 weeks each spring – the 2024 course has now started and runs from 26 Feb to 29 May. It’s an advanced studio course in which students work in multidisciplinary teams to address project briefs commissioned by governmental ministries in Finland. The course proceeds through the spring as a series of teaching modules in which various research and design methods are applied to address the project briefs. Blog posts are written by student groups, in which they share news, experiences and insights from within the course activities and their project development. More information here about the DfG 2024 project briefs. Hold the date for the public finale on Wednesday 29 May!

Dear team,

it is great to see how the work is progressing. I really like your metaphore approaches, Russian Doll and Self-fertilization. personall’y I also build on those. It is good to remember also the Hidden Agendas and the issue of Power, so maybe you later want and need to dig into those when we get into real business…