This blog post reports on work-in-progress within the DfG course! The post is written by Suvi Onne, a member of group 2A. Together, we work in collaboration with the Ministry of Transport & Communications’ brief on ‘how to make Finland’s public transport system more accessible’. The group 2A includes Gabriel Fuentes from the Collaborative & Industrial Design program, Katrina Hoffmann from the Collaborative & Industrial Design program, Suvi Onne from the Creative Sustainability – Chemical engineering program, and Mina Rostami from the Creative Sustainability – Design program.

Written by: Suvi Onne

While looking at research conducted in Norway, we came across the term “universal accessibility”. (Aarhaug & Elvebakk, 2015). The term represented everything we pictured in terms of accessibility goals. A type that doesn’t specify, exclude the needs or benefits of accessibility. We understood this term as meeting all requirements and removing obstacles to improve the use of public transport and in general, making it an accessible and pleasant means for all.

A conflict of perspective

Accessibility implementation happens on a system level but then at the same time, the user experiences it at a more micro, detailed level too. Based on interviews we conducted with users who are using wheelchairs for mobility and their experiences of public transport chains and their accessibility in everyday life. Oftentimes, services and places are explicitly accessible on paper, yet, reality doesn’t match this expectation. Problems with reliability can become social barriers to using public transport. Users need to evaluate the accessibility of the information given and decide if the travel chain from their location to their destination would be accessible for their use. Weather, and especially winter weather, can bring barriers, especially to public transport users using assistive devices for mobility wheelchairs, etc. (Lindsay & Yantzi, 2014). Our initial concern about this was further confirmed as we carried out interviews. Something that stayed on our minds was the story of a user who, as much as they use public transport in summer, finds it hard to do the same in the winter months.

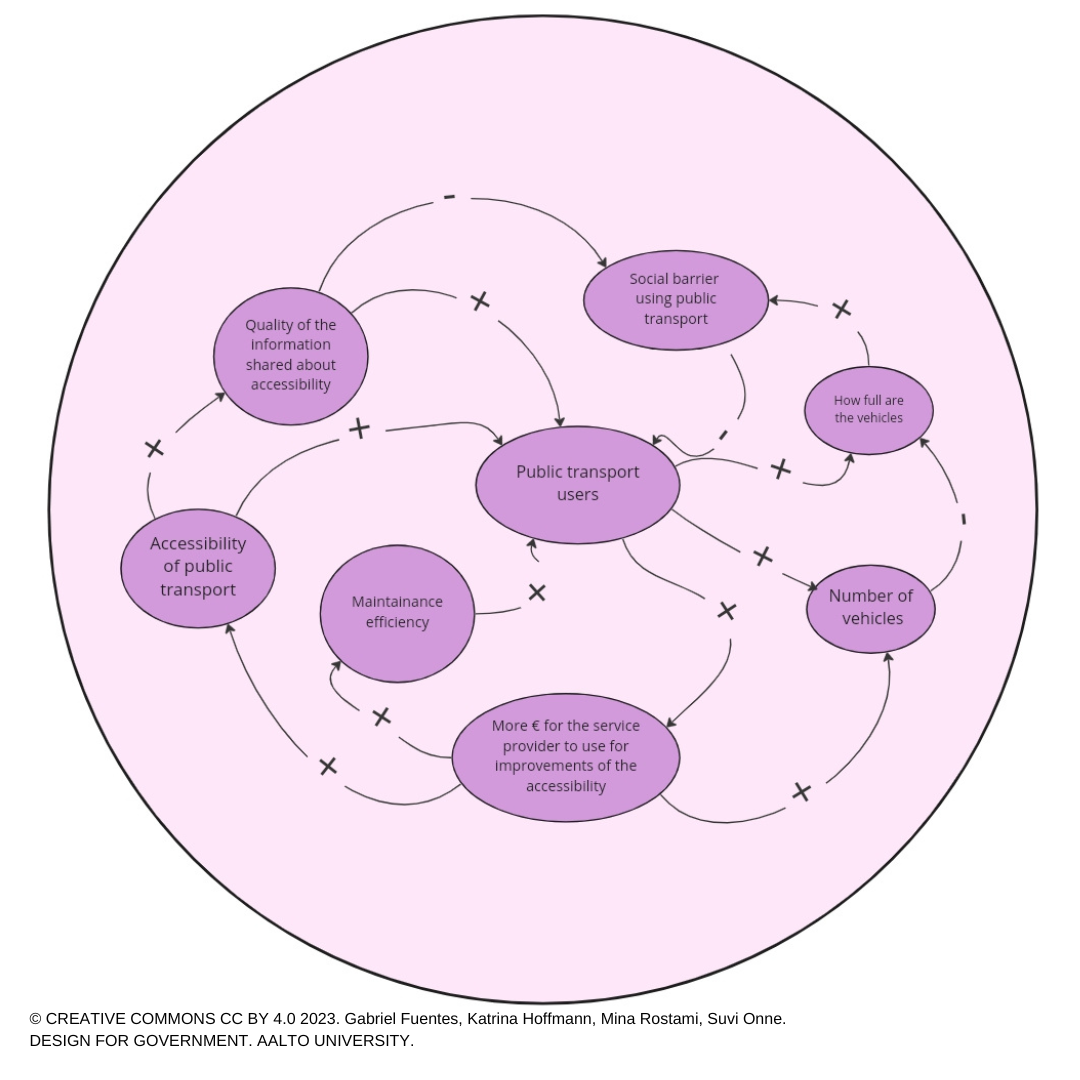

Causal loop model of the accessible public transport

Through the interviews, we also got an insight that contradicts the notion of universal accessibility, which we first had in mind as a desired outcome. In this regard, universal accessibility can still be a desired outcome. Yet, it is essential to recognize that it shouldn’t focus solely on disabilities, but rather on accommodating a diverse range of needs (interviews) (Velho et al, 2016). Currently, a pram and a wheelchair are placed in the same areas on buses and trains. On trains, it is even possible that a person with a wheelchair has bought a ticket for the trip, but when entering the train, the area is already occupied by prams.

Bus drivers’ role within micro- and macro-level structures

In some cases, drivers’ or personnel’s actions and attitudes can also affect and especially build barriers. These actions could be ignoring to assist a wheelchair user when boarding or insisting on getting the assistance they are entitled to. This was brought up by Velho et al (2016), and in interviews we had with both service operators and with users interviews. Finding the root cause behind the lack of adequate skills among service staff might be crucial when achieving accessible transport chains in Finland.

Mid-term presentation

The service providers and other actors within the public transport system, whom we have talked to during the project this far, all share the vision to improve accessibility. Despite having similar visions, the needed work towards common goals is unmet. This seems to be because the responsibility for the overall picture is not allocated to anyone. As a result, it is overlooked and not seen as an opportunity. The drivers in buses and trains are one of the connections of micro- and macro-level, and maybe they could be the connecting leverage point to make changes in the system towards accessibility. (Meadows, 2009)

Overall, achieving universal accessibility requires a more empathetic approach that considers both physical and social factors not only at the system level, but also on a small scale. We can build more inclusive and equal transport chains by addressing the systemic and individual barriers that prevent users from accessing and using public transport.

References:

Meadows, Donella H. (2009). Thinking in systems : a primer. London ; Sterling, VA :Earthscan

Jørgen Aarhaug, Beate Elvebakk (2015) The impact of Universally accessible public transport–a before and after study, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2015.08.003

Sally Lindsay & Nicole Yantzi (2014) Weather, disability, vulnerability, and resilience: exploring how youth with physical disabilities experience winter, Disability and Rehabilitation, 36:26, 2195-2204, DOI:10.3109/09638288.2014.892158

Raquel Velho, Catherine Holloway, Andrew Symonds, Brian Balmer (2016) The Effect of Transport Accessibility on the Social Inclusion of Wheelchair Users: A Mixed Method Analysis, DOI: 10.17645/si.v4i3.484

LVM – Liikenne- ja Viestintäministeriö (2022) Joukkoliikenteen matkaketjut vammaisryhmien näkökulmasta—Esteettömyysdemon demo

Interviews

The DfG course runs for 14 weeks each spring – the 2023 course has now started and runs from 27 Feb to 31 May. It’s an advanced studio course in which students work in multidisciplinary teams to address project briefs commissioned by governmental ministries in Finland. The course proceeds through the spring as a series of teaching modules in which various research and design methods are applied to address the project briefs. Blog posts are written by student groups, in which they share news, experiences and insights from within the course activities and their project development. More information here about the DfG 2023 project briefs.