This blog post reports on work-in-progress within the DfG course! The post is written by group 2A dealing with the Ministry of Finance’s brief on New governance model. Employee perspective. The group includes Frans Astala from Creative Sustainability Business program, Kristen Barretto from Collaborative and Industrial Design program, Florencia Pochinki from Creative Sustainability Business program, and Falguni Purohit from International Design Business Management program.

Written by: Frans Astala

Finland is currently undergoing the largest change in employment services in decades. Compared to our Nordic peers, Finland has had relatively high unemployment rates. The current government has set out to improve this by overhauling the employment services by shifting from a centralized system to one where the services are provided by the municipalities. (Aho et al., 2022) The reform is influenced by the success of the “Nordic model”, particularly a similar reform implemented in Denmark in 2007. The end result is envisioned to improve the employment rate, to be more innovative and flexible, with more focus on the individual job seeker’s unique situation and needs. The municipalities are expected to coordinate activities with local learning institutions and businesses to find solutions to the employment mismatch problems locally, among other things. (Aho et al., 2022)

All of these things are being piloted in several municipalities, so practical experience is currently being accumulated in different places simultaneously. The reform is set to take full effect in 2024. With the formulation of the legislation still on going, there are a lot of moving parts and unknowns. There are many different actors who need to coordinate their work in new ways.

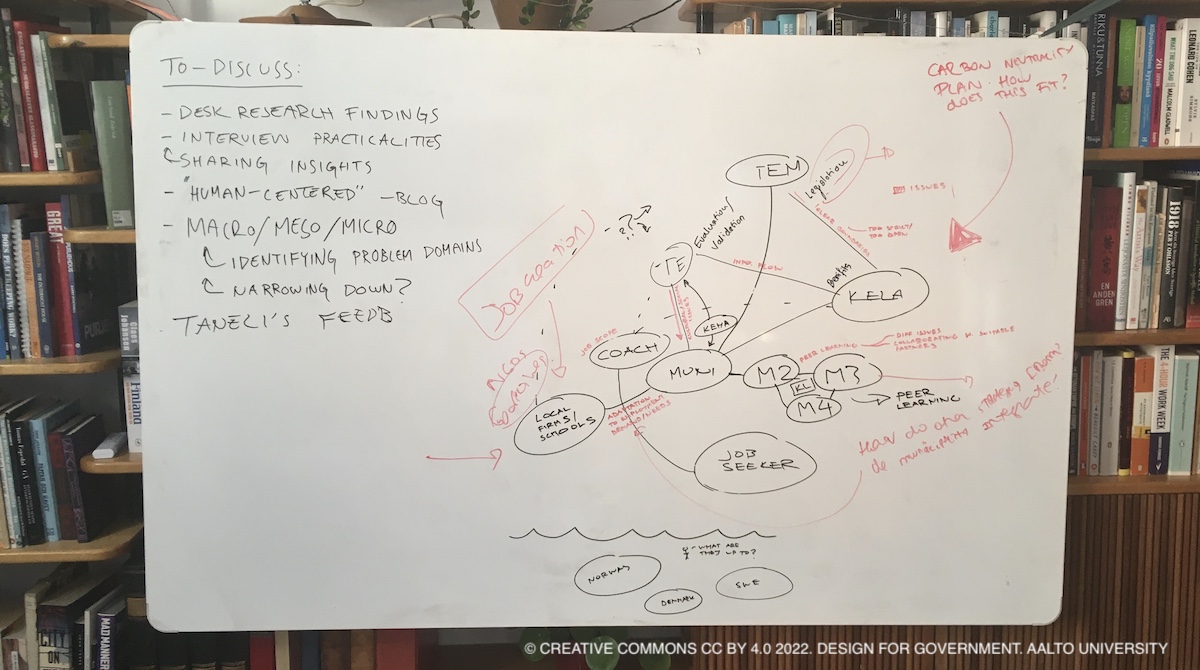

What makes this reform especially tricky is the myriad of different actors involved, with the municipalities taking a central role in the activities requiring coordination between KELA, employment services, ministries, local learning institutions, businesses, and others. This coordination needs to happen in a way that produces a good and effective experience for the job seeker.

Our brief is to focus on the public servants’ needs in order to ensure collaboration between different parties in a way that produces a people-centered outcome.

First steps in trying to understand the stakeholders’ perspectives

Starting to work with a brief like this is not easy. The public servants are not a homogenous group with the same needs and won’t necessarily require the same solutions. It is thus important to understand how each stakeholder sees their role and situation. Conducting desk research was the first natural step we took as a group in understanding the reform. However, reports always reflect the point of view of those who wrote them, so in order to gain novel insights it is important to be able to formulate questions from your own point of view, and most importantly ask them.

All the groups working with the same brief collaboratively organized a round-table discussion with representatives from KELA, TE-office, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment and the city of Espoo. We asked them about goals, their perceptions on successes and challenges, and current activities among other things. After some initial introductions, the conversation started flowing and we managed to gain valuable insight into how the different actors see this reform. One viewpoint shared by all of them was that the jobseeker perspective needs to be put at the center of the process, and to work with “yhden luukun periaate” (one-stop shop -principle). Another point that arose was the need for improvement of information flows and collaboration. The uncertainties of the ongoing formulation of legislation and pilot experiments were also reflected in the discussion by several parties. As a representative of Kuntaliitto aptly put it; what is needed is “not only collaboration, but working together.”

It is easy to get swamped with information and data when trying to understand a complex issue. While it is important to gain an understanding of the big picture, at the same time it is also important to understand the relevant details. In the end, our goal is not to influence the legislation, but to bring a design perspective into the mix in a way that can help the people in this system.

Human-centered framing of the reform

Our team work has greatly benefitted from the different kinds of backgrounds that all the members bring to the table. A design student and a business student look at things from different perspectives, and that helps us gain a richer understanding as a group. What does human-centered mean in this context?

According to Rouse (2007), human-centered design seeks to incorporate concerns, values and perceptions of all stakeholders in a balanced way. User-centricity would bring the focus to the job-seekers, perhaps the primary stakeholder in this case, but there are a lot of stakeholders, and the entire system consists of humans who will bring about the reform in practice.

Much of our early work as a group was an effort in trying to understand the reform itself, the pieces and the whole. But the reform as a whole is not what makes it human-centered, but rather the relationships between the different actors. Based on desk research such as reports, and the round table discussions, our group set out to identify relations of interest and deepen our understanding of them. One such relation is the collaboration and peer-learning between municipalities, and another example is the collaboration between municipalities, local businesses and learning institutions. The collaboration between KELA and TE-office is yet another crucial relation that needs to function in order for this reform to reach its goals.

Going forward

Trying not to jump into solutions is difficult but necessary. Everything looks like a nail when you are holding a hammer, so one should have the patience not to open up the toolbox yet and try to understand the problem first. We are shifting from trying to understand the nature of the reform into trying to understand the relationships within the reform, and finding the relevant ones to focus on. As we move into more in-depth interviews in the coming week, we have more questions than what we started with, but all of this serves the framing of the problem in a way that we can eventually start working out a solution for.

References

- Aho, S., Arnkil, R., Hämäläinen, K., Lind, S., Spangar, S., Tuomala, J., … & Mäkiaho, A. (2022). Työllisyyden kuntakokeilujen arviointi: I väliraportti.

- Rouse, W. B. (2007). People and organizations: Explorations of human-centered design. John Wiley & Sons.

The DfG course runs for 14 weeks each spring – the 2022 course has now started and runs from 28 Feb to 23 May. It’s an advanced studio course in which students work in multidisciplinary teams to address project briefs commissioned by governmental ministries in Finland. The course proceeds through the spring as a series of teaching modules in which various research and design methods are applied to address the project briefs. Blog posts are written by student groups, in which they share news, experiences and insights from within the course activities and their project development. More information here about the DfG 2022 project briefs. Hold the date for the public online finale online 09:00-12:00 AM (EEST) on Monday 23 May!