This blog post reports on work-in-progress within the DfG course! The post is written by group 1C dealing with Metsähallitus and the Ministry of Environment’s brief on ‘sustainable nature recreation.’ The group includes Iines Reinikainen from the Creative sustainability program, Kazuki Mori from the Collaborative & Industrial Design program, Kazuichiro Taira from the Spatial planning & Transportation Engineering program, and Laura Monten from the Collaborative & Industrial Design program.

Written by: Iines Reinikainen

Design during the Anthropocene

Our past months have been spent circulating one question: what is the future of sustainable recreation in Finland? We were provided with this problem by Metsähallitus, a state-owned enterprise that uses, manages, and protects state-owned land and water areas. And what would be the biggest environmental sustainability issue for 4 students to tackle in 12 weeks? Biodiversity loss, of course!

So, let’s first talk a bit about biodiversity and Metsähallitus.

Biodiversity means the variety of life (AMHN, n.d.). When we are losing biodiversity, we are not only losing species of insects, birds, and moss – we are losing life. These species are the crucial parts of the ecosystems that also support human societies, economies, and cultures, and fulfill our very basic needs such as food and fresh water. We as humans are not alive without the life of the rest of nature, we are dependent on it. (IPCC, 2022).

Even with decades of visions, pushed-back goals, and programs from different political entities and Metsähallitus, the number of threatened species in Finland has been steadily growing, and in 2019 reached almost 12% of all Finnish species, the main being different forest management activities (The Web Service of the Red List of Finnish Species, 2019).

Metsähallitus manages all state-owned areas. In total, 12.6 million hectares of state-owned land and water areas are under Metsähallitus’ stewardship. To understand the magnitude: that is almost one-third of Finland’s surface area (Metsähallitus, n.d.).

This makes our client, Metsähallitus, the single main actor of biodiversity in Finland with a great responsibility for the future as well. Yes, often criticized one, but also the one doing concrete conservation on a large scale and great potential to have a positive impact on Finnish biodiversity, of course also depending on the goals and budgets coming from the ministries.

To be clear: we are in the era of the 6th mass extinction (YLE, 2020). It is not dramatic to say that the Finnish governmental bodies are not in a position to push back the biodiversity action.

This setting created an undertone to my personal design process, in positive and negative ways. Thus, I wasn’t able to look at this project as just an interesting design problem. The scale and urgency of the issue felt sometimes quite overwhelming and personal, yet it felt still exciting to get a brief provided by Metsähallitus – an entity that has an actual impact on it.

Through this journey, it became clearer to me how important it is to not only recognize the greatest leverage points (D. Meadows) in sustainable transitions but also to come to terms with what is possible to do within the limits of the project. What is actually possible to be implemented to create any change? What would be the solution that has the actual potential to scale up, even if it would reframe the brief given by our client?

We began to think: What is the value of design during the Anthropocene? Can we use design to intervene in systems in a way that creates a channel for more-than-humans to be heard? Our final design proposal was mainly shaped by this background idea of the rest of nature often missing representatives in the boards and tables, where decisions are made.

Learning from the past

While conducting the interviews, we learned that Metsähallitus is full of brilliant professionals who have the biodiversity issue in their hearts and have the know-how to better the situation. What is missing then, to let these professionals do what they can?

Through qualitative research methods, we identified the following storyline: the different departments inside Metsähallitus are “walking different paths in the same forest”. They all operate in the same environment and might have the same ultimate goal (to conserve biodiversity), but their priorities, interpretations, and understanding of the issue might differ and the information flow between them is not always working.

To empathise with the different department’s perspectives, we created fictional characters, and profiles, representing each of the main operations. These profiles and their thoughts were informed by the interviews we had with the real Metsähallitus employees.

These tools were important in helping us to visualize our final proposal. They were used to navigate the amount of information and help us both imagine, explore, and explain the transformation we expect to happen in the organization.

© CREATIVE COMMONS CC BY 4.0 2022. Iines Reinikainen, Laura Monten, Kazuki Mori, Kazuichiro Taira. DESIGN FOR GOVERNMENT. AALTO UNIVERSITY

The aha-moment of our project came within the very last interviews we conducted to validate our initial ideas with the client. Several people mentioned the lack of talk during a coffee break – something they used to have before but is now unintentionally lost due to the development of the organization. The operational areas are now larger than they used to be, leading to the employees meeting their colleagues from different departments rarely, especially in an informal setting. From our client, we also learned that the organization would benefit from a “soft”, informal, action-oriented intervention approach.

Sometimes, to look into the future we have to look into the past. This guided our initial idea of the board who would discuss, represent and create an action plan for biodiversity, to something more human-size and casual: Coffee Table for Biodiversity.

Holistic solutions to a wicked problem

As our final proposal we initiated that by establishing local Coffee Tables including professionals from each main Metsähallitus department of the area and inviting stakeholders from research institutes, and local environmental organizations as well, this lost connection could be renewed. Through the Coffee Table discussions, several ideas would be agreed upon, and each participant would implement these ideas into reality. Outcomes can be, for example, biodiversity-first forestry planning, or regenerative tourism activities created between conservation and recreation departments and a local NGO.

Even though settling with just one idea meant saying goodbye to many others and a huge pile of data and research, I feel like all the different paths we took during the process were important for the final proposal. Without the initial visitor-oriented solutions, we wouldn’t be able to have the certainty to shift away from them.

We believe that through co-creation, with the help of an outside facilitator, Metsähallitus would be able to close the gap between departments on biodiversity understanding and put the biodiversity goals and visions into holistic practice, which considers the combined impact of different departments. Designing for a wicked issue, such as biodiversity loss requires various actors to solve. In the ecosystem, one thing affects another, which means also the solutions must consider the systemic nature of the issue.

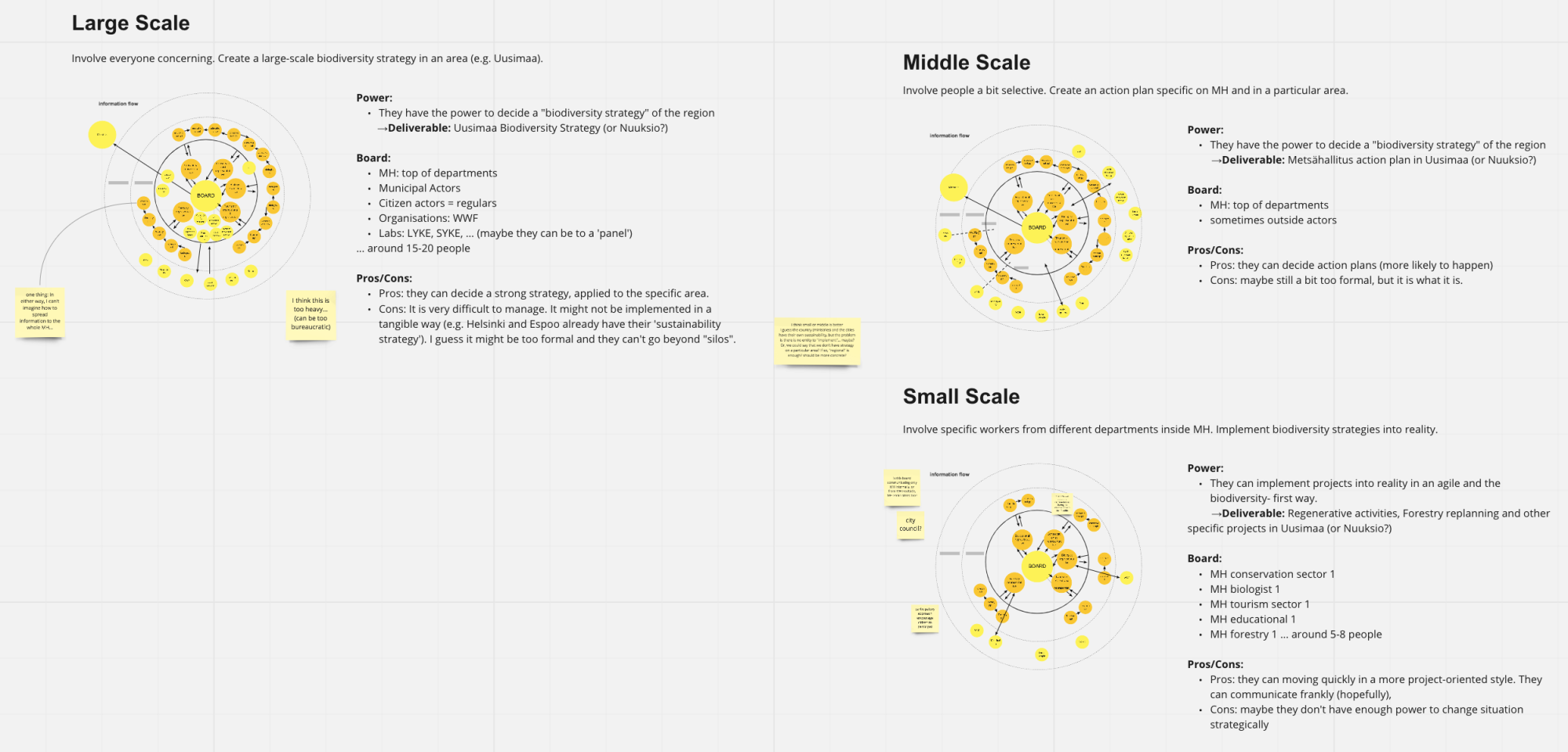

To define the most feasible size of the coffee table, we build different scenarios to understand the pros and cons of different outcomes. Experimenting with different structures, sizes, and the learnings from past Metsähallitus examples, employees helped us imagine the final structure.

© CREATIVE COMMONS CC BY 4.0 2022. Iines Reinikainen, Laura Monten, Kazuki Mori, Kazuichiro Taira. DESIGN FOR GOVERNMENT. AALTO UNIVERSITY

Since the problem we decided to tackle was the ‘lack of conversation and tangible holistic actions’, we adopted the small size, which allows people to communicate with each other more casually and frequently, and to implement actions in a more agile way. The benefits of large-scale are the ability to build large strategies, but it easily gets less frequent and too formal, including many interests to possibly overpower the biodiversity goals.

We initiate piloting [ABLL1] Coffee Table in the Nuuksio National Park area and adjacent areas. This pilot should include representatives from the conservation, recreation, and forestry departments from Metsähallitus, SYKE as a research entity, and Suomen Luonnonsuojeluliitto, WWF, and SCOUT as local organizations. We mapped out these participants by conducting interviews, following recent news and analyzing different stakeholders, their past projects, and their relationships with Metsähallitus.

© CREATIVE COMMONS CC BY 4.0 2022. Iines Reinikainen, Laura Monten, Kazuki Mori, Kazuichiro Taira. DESIGN FOR GOVERNMENT. AALTO UNIVERSITY

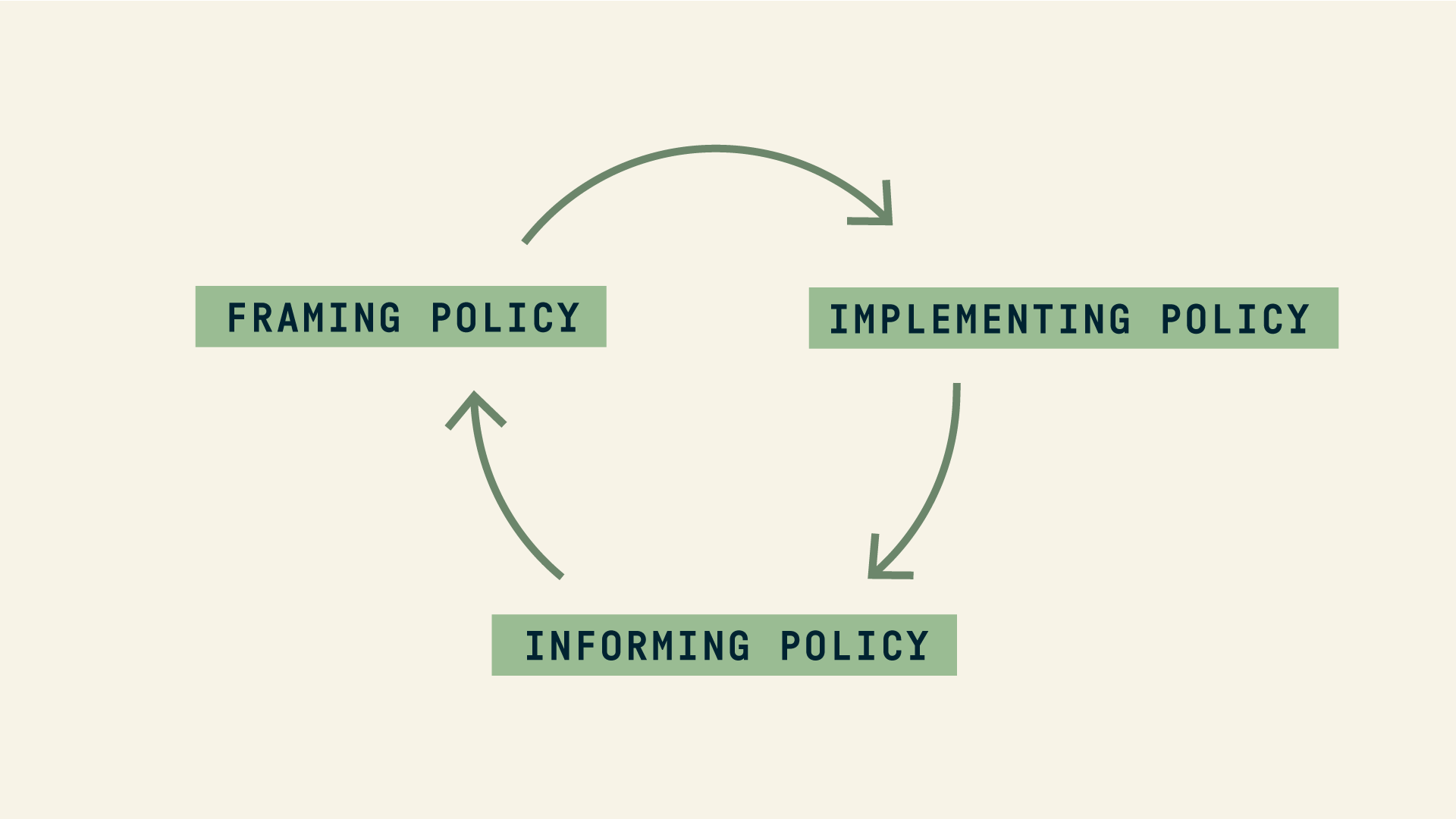

From implementing policy to actively shaping one

As design always considers the future, it has to be discussed in design solutions. Now, Metsähallitus is recognized as the organization that is in charge of recreation, conservation, and forestry – a policy implementor. We believe that Metsähallitus can play a much bigger role, by reshaping the policies and value it brings to society in a sustainable future.

To scale up, after the pilot project is evaluated, Metsähallitus could establish local Coffee Tables in new local areas. This means that in the future Metsähallitus could become the host of nationwide biodiversity discussions in Finland, providing a meeting point for practitioners, scientists, and residents to come together and work for biodiversity.

To give ownership of the Coffee Table to the participants, even if we suggest a certain timeframe and frequency, we believe that it should be adjusted. However, we think it is crucial to follow the steps of planning, implementing, evaluating, and discussing with ministries for the following reasons. The proposal is a “mid-stream” solution. On the one hand, it initiates change in the cooperation between internal operations, which will affect the practical level with visitors, forestry, and conservation practices. On the other hand, it is also a mechanism to affect policymaking.

Because the operations of Metsähallitus are dependent on each government and the budgets and profit goals they decide, the future of biodiversity is always uncertain and a political subject. The nationwide feedback from Metsähallitus hands-on practitioners will keep biodiversity in political discussion continuously. This means that the solution is implementing the existing policies but informing new ones as well.

Adapted from: Juninger, S. (2013) Design and Innovation in the Public Sector: Matters of Design in Policy-Making and Policy Implementation

As mentioned, a project like this inevitably raises the question of what is the concrete value needed from Metsähallitus in the future. This is what is left to our clients, Ministries of Environment, Ministry of Agriculture and forestry, and Metsähallitus, as well as designers for government to consider: Is it economic growth, timber wood, and nice parks to visit? Can the crisis of ecosystems wait until the everchanging political will is there to conserve the rapidly decreasing nature? Or could a governmental enterprise be the initiator of a live environment for future generations of humans, insects, birds, and moss?

Lastly, I would like to thank my amazing group members and teachers, as well as everyone who participated in our project: interviewees, and those who answered our questionnaire. Special thanks to all the Metsähallitus partners and employees, who gave us their time and effort.

The DfG course runs for 14 weeks each spring – the 2022 course has now started and runs from 28 Feb to 23 May. It’s an advanced studio course in which students work in multidisciplinary teams to address project briefs commissioned by governmental ministries in Finland. The course proceeds through the spring as a series of teaching modules in which various research and design methods are applied to address the project briefs. Blog posts are written by student groups, in which they share news, experiences and insights from within the course activities and their project development. More information here about the DfG 2022 project briefs.

Sources:

American Museum of Natural History. n.d. What is Biodiversity? Retrieved on May 26th 2022 from:

https://www.amnh.org/research/center-for-biodiversity-conservation/what-is-biodiversity

IPCC. 2022. Climate change: a threat to human wellbeing and health of the planet. Taking action now can secure our future. Retrieved on May 25th 2022 from: https://www.ipcc.ch/2022/02/28/pr-wgii-ar6/

Metsähallitus. n.d. Retrieved on May 24th 2022 from: https://www.metsa.fi/maat-ja-vedet/pinta-alat/

The Web Service of the Red List of Finnish Species. 2019. Retrieved on May 24th 2022 from: https://punainenkirja.laji.fi/en/results

YLE. 2020. Käynnissä oleva sukupuuttoaalto on ympäristöongelmista vakavin – yhden eliölajin kuolema voi johtaa myös toisen katoamiseen. Retrieved on May 24th 2022 from: https://yle.fi/uutiset/3-11381435

YLE. 2021. Ensi viikolla alkavissa neuvotteluissa laaditaan sopimusta luontokadon pysäyttämiseen – tavoite on venynyt jo vuosikymmenillä alkuperäisestä. Retrieved on May 24th 2022 from: https://yle.fi/uutiset/3-12135389