This blog post reports on work-in-progress within the DfG course! The post is written by group 1B dealing with Metsähallitus’ and the Ministry of the environment’s brief on ‘the future of sustainable recreation’. The group includes Mantė Žygelytė, Ninni Laaksonen and Xinyu Zhang from Collaborative and Industrial Design program, and Sofia Wasastjerna from International Design Business Management program.

Since the last blog post, much has happened. By then, we had only been introduced to the brief and had a couple of interviews, as well as started mapping out the problem context based on our current understanding. Now, our work has already resulted in a couple of key insights which will guide our further work. The past few weeks have undoubtedly been intense, knowing that the mid-term presentations were approaching rapidly and that we then would have to present something to our client. Since we did not have much time for processing and reflecting, finding efficient ways of dealing with our gathered data turned out to be invaluable. In this blog post, I will share our recent progress and reflect on some of the methods we have used.

4 User-Centric Insights

Compared to last time, we have had time to familiarize ourselves with the topic of sustainable recreation in the future on a deeper level. To find a more concrete project scope, we narrowed down to Nuuksio national park, as the pressure is particularly big on parks close to areas where many people live (Leppänen, 2021). We furthermore learned that one of the biggest problems is new visitor groups consisting of inexperienced visitors (Haltia employee, personal communication 27.3.2022 & L. Neuvonen, personal communication, 29.3.2022), whose lack of knowledge or weak relationship to nature might result in behaviors that harm the forest, such as creating illegal campfire sites or letting the dog run free (T. Laine, Nuuksio foreman, personal communication, 16.3.2022). Our insights, which I explain below, are therefore focusing on this visitor group.

Figure 1: Four insights at different stages of the visitor journey

Insight 1: Information reach

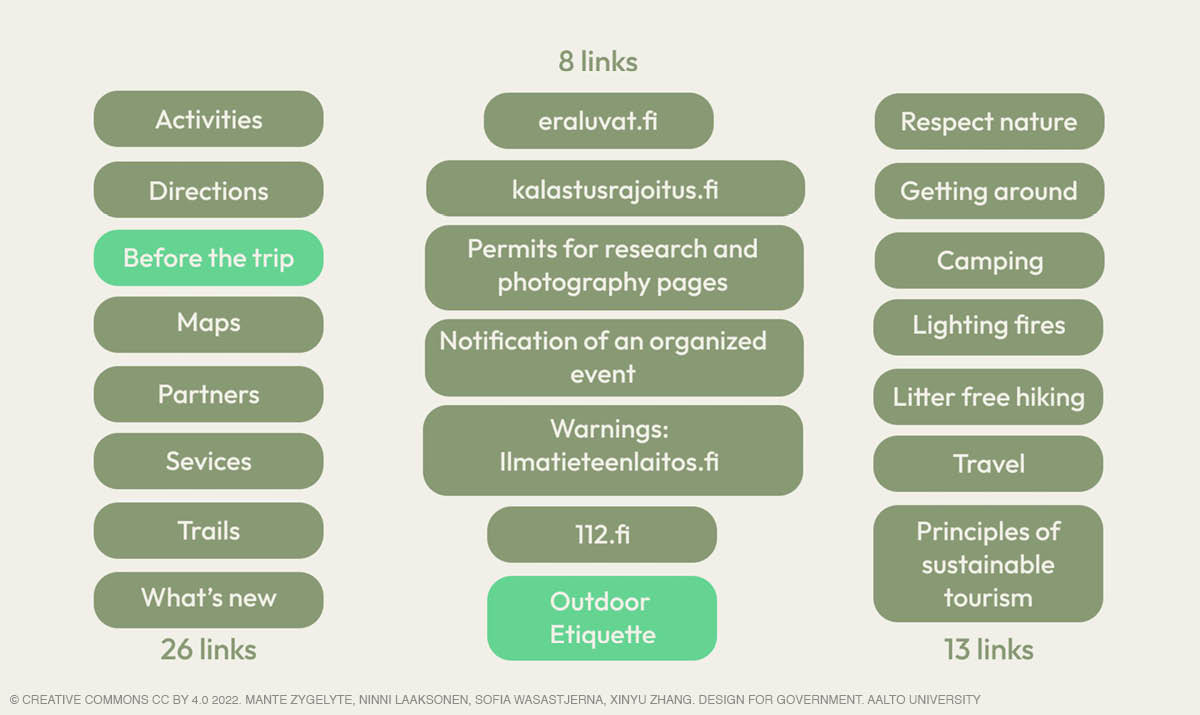

Metsähallitus’ efforts at compiling all possible information at luontoon.fi is impressive. However, although the information exists, it is probably too much to expect that all park visitors-to-be would browse their web page for hours prior to their visit. Figure 2

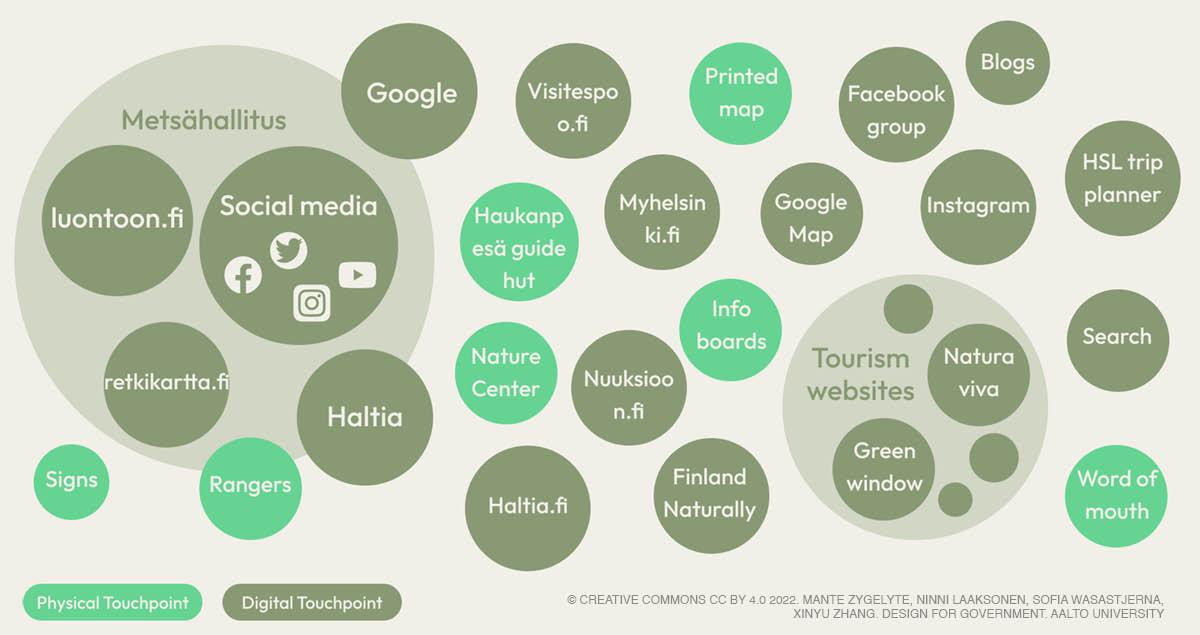

demonstrates the number of pages Metsähallitus’ wants the visitor to familiarize themselves with before the visit. In addition to Metsähallitus’ own channels, there is a huge amount of information channels by external parties which directly or indirectly might impact the visitor (some of these are shown in figure 3). For Metsähallitus, a major challenge is therefore to ensure that the right information reaches the user and serves their needs.

Figure 2: The “before the trip” reading flow the visitor is exposed to at luontoon.fi

Figure 3: Some of the various information channels park visitors might be impacted by

Insight 2: Spreading visitor pressure

One of the biggest problems seems to be that simply the number of visitors tears the nature. National parks are not the only places for nature recreation, still most people in the capital region choose to visit Nuuksio or Sipoonkorpi, likely because of the strong brand the national parks have gained (Leppänen, 2021 & J. Nippala, personal communication, 7.3.2022). When visitors choose to visit the national park, they also make an active decision about where to start their route. In Nuuksio, there are more than one possible starting point, although most visitors start from Haukkalampi (Haltia employee, personal communication, 27.3.2022 & L. Neuvonen, personal communication, 29.3.2022). There have been efforts in spreading the pressure from certain places and trails, for example the Parkkihaukka service that showed how busy parking places were (Metsähallitus, 2018). Everyone we discussed with mentioned this as a successful project, regardless of where they worked (e.g. L. Neuvonen, personal communication, 29.3.2022 & M. Valo, personal communication, 30.3.2022), but weirdly, the service is not maintained.

Insight 3: Infrastructure

The infrastructure in the park plays an important role in informing and guiding the visitor as well as providing options, for example through providing enough campfire sites so that visitors don’t need to solve the issue by creating their own. As Byers (1996, p. 37) says: “Lack of options can act as a barrier to behavior change”. According to our interview with Neuvonen (personal communication, 29.3.2022), specialty designer at Metsähallitus, the current infrastructure is designed for people who already know the rules and are familiar with national parks, while inexperienced visitors might need a different kind of support on site.

Insight 4: Relationship with nature

Many of the articles we read (e.g. Leppänen, 2021 & Mackay & Schmitt, 2019) explain that people who have a stronger connection to nature are more likely to engage in pro-environmental behavior. Newer visitors with less experience might therefore have a weaker relationship with nature which makes them more likely to cause harm to it. As Charles & Chapple (2018, p.11) puts it: “To get to action, the heart and hands are typically engaged as well”. It is therefore interesting that there are almost no regenerative activities for adults in Nuuksio (the types of activities which would strengthen their nature connectedness) – the existing activities are targeted mainly at nature lovers (e.g. events arranged by WWF) and activists, or children (for example Nature School).

As we presented our ideas to our clients in the mid-term presentations, we were happy that the presentation resulted in a good discussion about Metsähallitus’ and the Ministry of the Environment’s thoughts on the insights. While they regarded all insights as relevant, the last insight about the relationship with nature seemed to spark most interest and was also the insight which they unanimously encouraged us to explore further. We do not yet know where our project will end up, however, it is nice to keep in mind that our project ultimately seeks to help our client increase their understanding or take action.

How We Got There: Finding the Right Tools for Dealing with Data

One thing that I personally looked forward to in this course was to get to practice systems mapping. Some previous courses I have taken have touched upon systems thinking theory, but I looked forward to getting some practical experience. In the context of this course, we were encouraged to use systems mapping as a tool for reaching a thorough understanding of the problem and identifying possible problems or places to intervene, as well as a tool for communication.

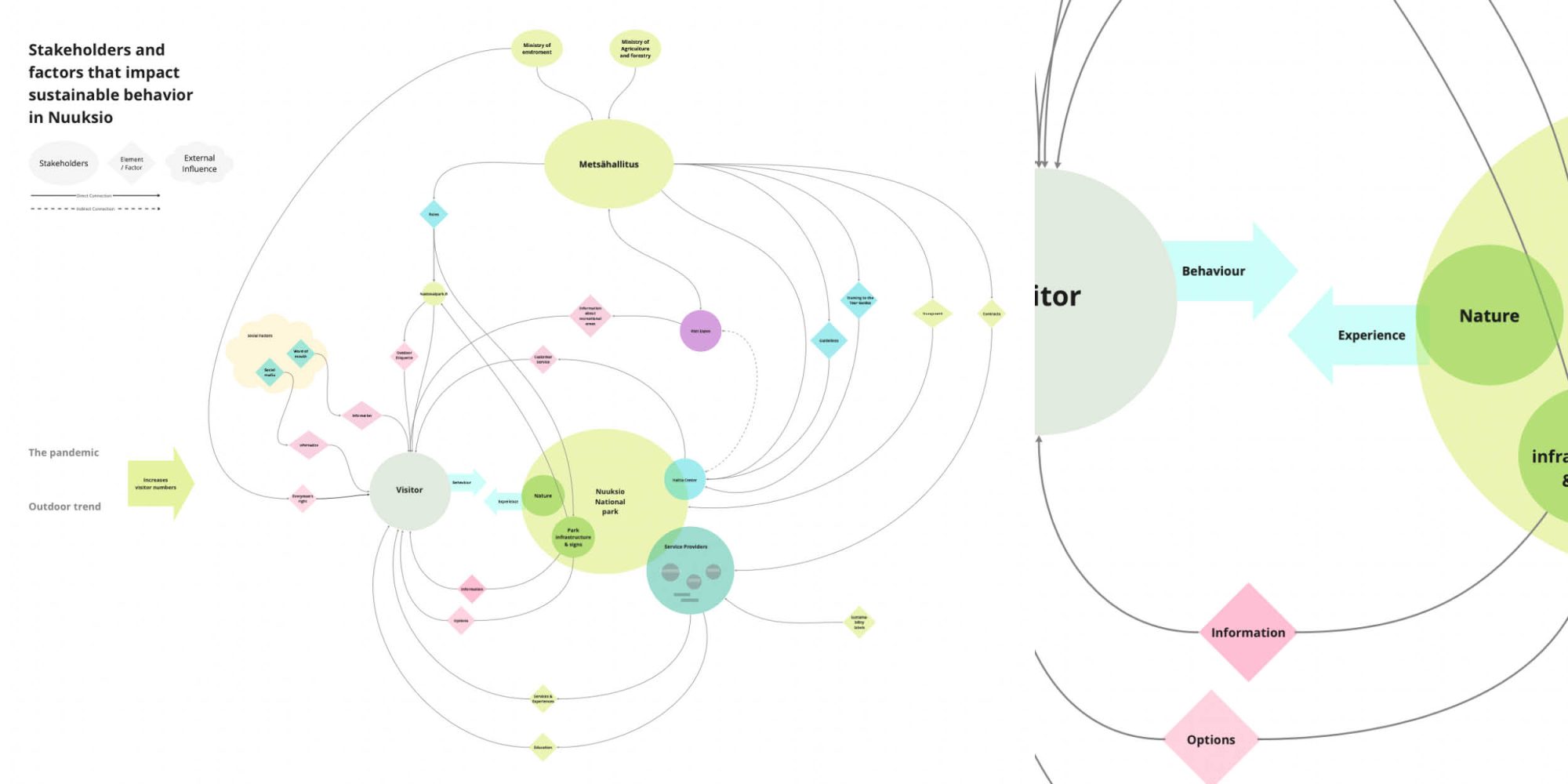

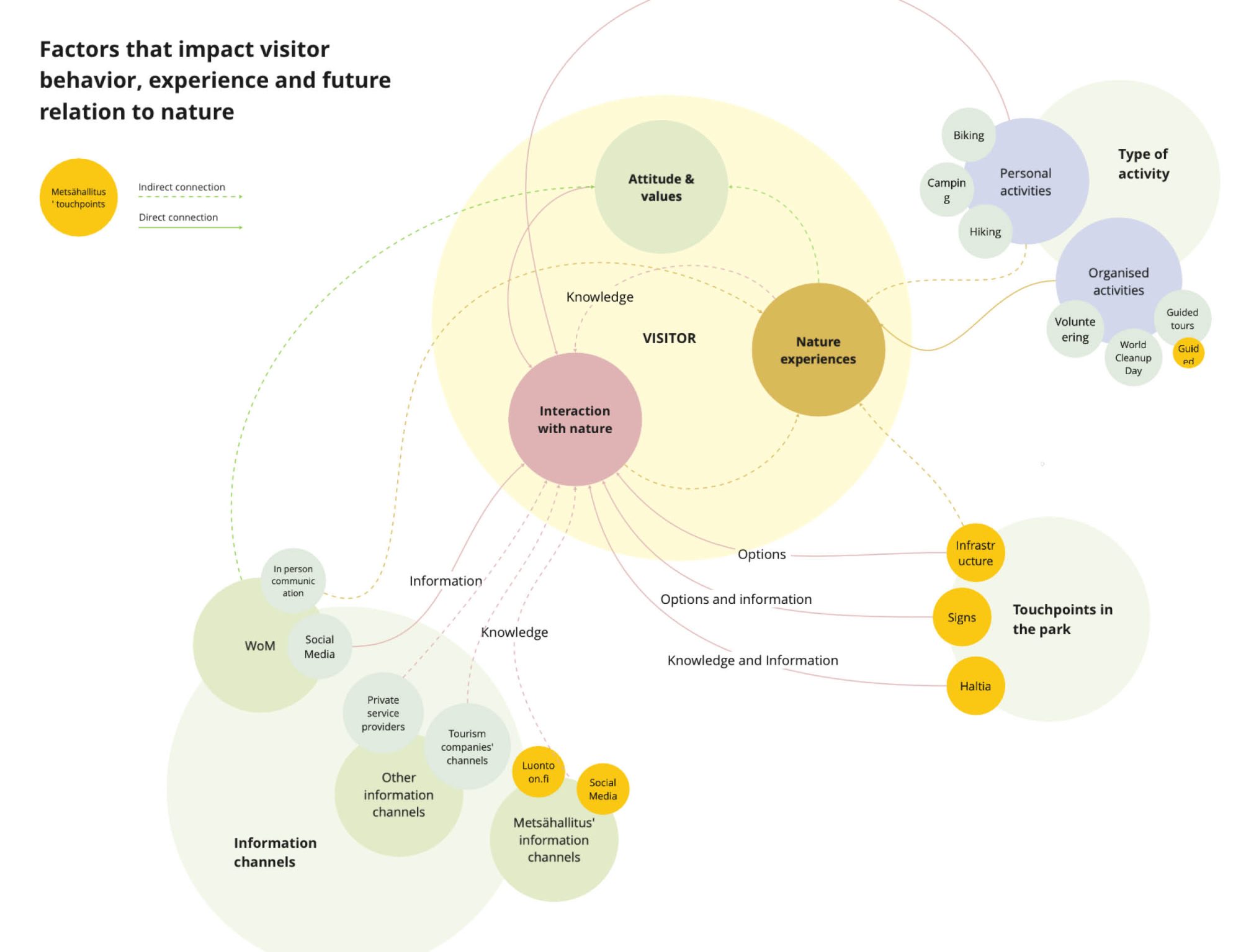

I believe that I, for the sake of my whole team, can say that we were surprised by how difficult it actually was to make a visual representation of the problem in the national parks. Firstly, we had to let go of the idea that there is one right picture of the system, since all systems maps at their core are just interpretations of a system. Secondly, it took us a while to understand that the perhaps most important stage of the mapping is deciding what should be portrayed, i.e. the purpose of the map (Arena & Li, 2018). We tried different iterations: we mapped the connections between all stakeholders directly or indirectly related to the context of Nuuksio national park and we made a version focusing on the different information flows that might impact the visitor. When we showed this map to visiting lecturer and systems expert Esko Reinikainen, we were in fact encouraged to explore what we vaguely had placed in the middle: the relation between human behavior and nature experience and the factors that impact these. This latter attempt to map the system explains our fourth insight about relation with nature. It still needs some work, but will likely be valuable if we choose to explore this path further. These attempts at portraying the system can be seen in figure 4 and 5.

Figure 4: Our first attempt at systems mapping, where the feedback highlighted that the arrows in the middle could be worth discovering more.

Figure 5: A systems map that explores how different factors impact how the visitor interacts with nature, the nature experience, and ultimately, the attitudes and values.

Although we likely are not yet skilled enough to access the true potential of systems mapping, we had to accept that drawing a map of the system would not be a gateway to magic solutions. For our team, it was the combination of tools that turned out to be valuable when dealing with the massive amount of data we had gathered. Using the technique of affinity diagramming, i.e. adding pieces of data from different sources to one single workspace and arranging the data according to emerging themes, we were able to notice recurring problems and form insights based on them. The systems thinking exercise helped us understand which actors play a role in the problems, and mapping the visitor journey was valuable for looking at the insights from the customer’s point of view and understanding where in the visitor journey the problems occur.

The Value of Trust and a Realistic Outlook When Working Within a Time Frame

In the research phase, a challenge for our team was to accept that enough is enough. Due to the limited time frame, we at some point had to close our initial research phase in order to have something to present at the mid-term event. It is true that we did not have time to read every single page online nor conduct as many interviews as we would have wanted, but I believe that our first insight about the huge amount of information channels shows that it would have been an impossible undertaking. However, we managed to gather an amount of data which served its purpose – we now have insights which we soon can start evaluating and ideating upon. Although it is likely that we will continue conducting research in some form – it would for example be interesting to learn more about our particular user group and somehow engage the stakeholders in co-designing our solution – I believe that we now know the importance of staying realistic.

The last few weeks have furthermore made us realize the importance of trusting each other. Dealing with a pressing schedule forced us into utilizing our resources in an efficient way and delegating the work. This meant that everyone by no means was able to read everything nor participate in all interviews. We needed to rely on each other’s capability of taking in information and synthesizing it. It was not an easy task, but it certainly built the trust we have in each other as team members. As we are three teams working on the same brief, we were also encouraged to collaborate across the teams in gathering data, to once more increase the efficiency and be able to access more data. I have to admit that I was skeptical towards this approach – wouldn’t a common database lead to way too similar insights? What was interesting to see, however, was that although we shared our knowledge within the teams, all teams naturally found their own approaches for the mid-term presentations, focusing on different visitor groups.

It is a relief to have made it through the ambiguous first phase of the project, and we are eager to soon enter the phase where we actually are allowed to start ideating ways to intervene. But first: a well-deserved Easter break!

References

Arena & Li (2018). Guide to Civic Tech & Data Ecosystem Mapping. Civic Tech & Data Collaborative. Retrieved 8.4.2022 from: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/98649/guide_to_civic_tech_and_data_ecosystem_mapping.pdf

Byers, A. B. (1996). Understanding and influencing behaviors in conservation and natural resource management. African Biodiversity Series, 4.

Charles, C. & Chapple, R. S. (2018). Home to us all: How connecting with nature helps us care for ourselves and the earth. Nature for all.

Leppänen, T. (2021). Retkeilyn hullu vuosi. Latu & Polku. Retrieved 8.2.2022 from: https://www.latujapolku.fi/uutiset/retkeilyn-hullu-vuosi.html

Mackay, C. M. L. & Schmitt, M. T. (2019). Do people who feel connected to nature do more to protect it? A meta-analysis. Journal of Environmental Psychology 65, p. 101323. Metsähallitus (2018). Parkkihaukka auttaa autoilijaa ja reittipalvelu esittelee uusia vaihtoehtoja. Retrieved 7.4.2022 from: https://www.metsa.fi/tiedotteet/parkkihaukka-auttaa-autoilijaa-ja-reittipalvelu-esittelee-uusia-vaihtoehtoja-nuuksioon/

The DfG course runs for 14 weeks each spring – the 2022 course has now started and runs from 28 Feb to 23 May. It’s an advanced studio course in which students work in multidisciplinary teams to address project briefs commissioned by governmental ministries in Finland. The course proceeds through the spring as a series of teaching modules in which various research and design methods are applied to address the project briefs. Blog posts are written by student groups, in which they share news, experiences and insights from within the course activities and their project development. More information here about the DfG 2022 project briefs. Hold the date for the public online finale online 09:00-12:00 AM (EEST) on Monday 23 May!