This blog post reports on work-in-progress within the DfG course! The post is written by group 1C dealing with Metsähallitus’ brief on ‘The future of sustainable nature recreation’. The group includes Kazuichiro Taira from Spatial planning and Transportation programme, Iines Reinikainen from Creative Sustainability programme, Laura Monten and Kazuki Mori from Collaborative and Industrial Design programme.

Written by: Kazuki Mori

Our client is Metsähallitus, which manages mainly national parks in Finland, maintaining trails or conserving natural environments. The main conflict they have recognised is the contradiction between promoting visits and activities to national parks to enhance health and well-being and conserving biodiversity there, which we have been addressing.

In this first blog post, I will attempt to outline what we have done, what we grasped and what we will do so far.

Entangled actors and factors

Firstly, I will introduce our current research question: “How to increase people participation in sustainable environmental recreation (in Nuuksio)?” Let’s say, we set it two weeks ago and already know the question is vague and we have to explore more specific and decent expressions. However, when we faced the project, we immediately recognised that the problem is situated between unbelievably entangled and complicated factors, which our question reflects.

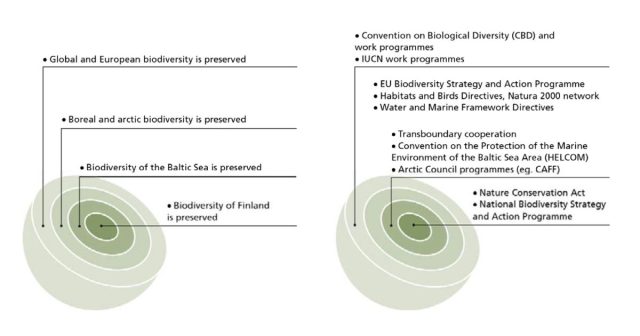

“Conservation” or “biodiversity”, for example, already has controversial aspects. Would saving threatened species directly mean “conservation”? Then, should we stop cutting woods or visiting National Parks? However, traditional (so to speak, “artificial”) biotopes have been regarded as one of the essential habitats for certain threatened species (Metsähallitus, 2016). So what can we do? In addition to that, we have of course recognised more difficulties: what “recreational tourism” is going on? What if “sustainable education”…? Speaking more, each discipline is surrounded by different level entities–local residents, forest owners, municipalities, ministries and the EU.

Figure 1. Focusing even on one word, you may find it is surrounded by multiple actors and regulations (Metsähallitus, 2016, p.13).

In other words, the issue we are facing consists of subtle political relationships between conservation or restoration, forestry, tourism, education and between different stakeholders.

For example, Sarkki, Heikkinen & Puhakka (2013) reported one of such cases in Oulanka National Park. In the process of adopting an international certification called PAN Parks, the PAN Parks team suggested that all hunting should be prohibited. On the other hand, in that area, local people have hunted reindeers and other animals, which has been one of their livelihoods. In other words, there was a conflict between the world view that users should leave nature untouched and that users are “an integral part of nature” (Sarkki, Heikkinen & Puhakka, 2013, p.41). In this case, it was reported that Metsähallitus played the role of “boundary organisation” between two opposite entities to resolve the conflict. This clearly tells us that things are generative–being continuously constructed, as Tim Ingold (2013) pointed out.

Diving into a person who is there

Despite such struggle, however, through numerous papers and webpages and four interviews, we are getting to know what we are facing, from abstract to concrete level. I would like to show some results in this part.

Firstly, I found that Metsähallitus has done a lot literally. For example, it has worked on specific local practices such as saving Saimaa ringed seals (Metsähallitus, 2018) or maintaining trails. In addition, Metsähallitus has attempted to communicate with local organisations, the forestry industry and tourism industry around the parks and other protected areas, and to develop protected area networks called METSO through agreements with forest owners (the Ministry of the Environment and Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2015), and so forth.

Figure 2. Metsähallitus is conserving the Saimaa ringed seal from 2020 to 2025 (Metsähallitus, 2018).

In terms of a human-centred perspective, we understand what was going on in the parks. For example, Nuuksio has a lot of local people who walk their dogs. Dogs can sometimes scare some animals in forests, but it would look like a tiny problem. However, the Nuuksio Foreman mentioned that this could be one of the significant threats: although visitors often assume “just one person then fine”, a massive number of visits to a relatively small area would magnify any tiny problems very quickly.

In addition, a mid-level visitor told us that while his first interest was to socialise with his friends, visiting parks multiple times made his mindset change to leave the place in a better condition than it was, for example, by picking garbage.

Through interviews, I was impressed that many workers of Metsähallitus wished for visitors’ well-being. Please let me introduce a bit:

“We hope it would be a win-win situation that we get the Finnish people out into nature and they may hopefully experience the well-being of being out there” ( a recreation specialist, Metsähallitus).

Possibility of bridging islands

Based on our research, I might point out a possibility–bridging different “islands of an archipelago”. For example, due to the organisation size of Metsähallitus, some pointed out that the communication between the maintenance and restoration team could be difficult and be enhanced more. Connecting both sides might contribute to developing new activities combining “restoration” and “activities (tourism)” sides.

Moreover, it can be said that there is another border between Metsähallitus and other organisations. While it is the fact that Metsähallitus has actively promoted the connection with organisations and private companies, we have heard that Metsähallitus can explore the possibility of collaboration with local organisations more.

However, I would have to say my recognition is still too broad. From the visitor’s perspective, we might need to explore: do people think they want to participate in regenerative action? Even if you have to pay? Or do you join if there is an association for restoration you can join? Also, on the provider’s side, we could identify what organisations provide what activities. Also, we are planning to go to a national park within two weeks, and then we will obtain a more viable sense and specific direction.

Let me try to think about the next period. We will need to identify at least one specific regenerative action in which visitors or local residents can participate collaboratively. It would function as so-called scenario planning, which “make it visible” (Manzini, 2015, p.121), speaking up about what they can do specifically in the future.

Subsequently, considering Metsähallitus itself is not the main actor to provide regenerative tourism, a framework or a system would be required to implement it in a broader way. For example, the City of Bologna adopted the concept of the City as a Commons to “re-situates the city as an enabler and facilitator” (Foster & Iaione, 2015, p.289). In this scheme, the city supports citizens through thinking together about what they can do and ensures their right to use specific public spaces. It could also be possible for us to encourage the Metsähallitus to be such an enabler in Finland’s nature.

Of course, what I have written so far is just a hypothesis. (I hope…) I could enjoy changing our pre-thoughts continuously.

Small reflection: accepting uncomfortable

This first blog introduced the problem we are addressing, what we have done, and the possibility we would take. As I already mentioned, the situation is complicated because it has been continuously affected and constructed by a wide range of stakeholders. However, we are getting a definite sense of visitors and users step by step and touching on a possible direction: bridging different groups inside Metsähallitus or different organisations. However, it can be said that we need to do deeper research on the visitors’ thoughts on regenerative tourism and what some organisations are doing.

Lastly, I will finish with my own reflection. I should have planned to go on-site much earlier–-I re-recognised that I am one who designs through diving on-site and, after that, connects my sense or intuition with facts and stats. In short; I can’t wait to visit Nuuksio! Also, this project requires us to accept the fuzzy “uncomfortable” for a while. Yes, I’m feeling very uncomfortable with the uncertainty of where to start, what we are doing and which direction to go. Sometimes I might be crazy to want to get the point, but I hope my team members can manage my impatience 😉

My team members, I’m happy to be with you. And, of course, keep up the great work!

Relevant links to further information

National Forest Strategy 2025

FOREST BIODIVERSITY AND PROTECTION

Habitats Management and Restoration at Metsähallitus

Fostering our Future – Metsähallitus Annual and Responsibility Report incl. Financial Statements 2020

Helmi Habitats Programme 2021-2030

METSO programme

Principles of Sustainable Tourism – National Parks, Nature Sites, Historical Sites and World Heritage Sites

Sustainable tourism in protected areas. Guide for tourist companies

References

Foster, S. R., & Iaione, C. (2015). The city as a commons. Yale Law & Policy Review, 34, 281.

Ingold, T. (2013). Making: Anthropology, archaeology, art and architecture. Routledge.

Manzini, E. (2015). Design, when everybody designs: An introduction to design for social innovation. MIT press.

Metsähallitus (2016). Principles of Protected Area Management in Finland. https://julkaisut.metsa.fi/julkaisut/show/2005

Metsähallitus (2018). LIFE Saimaa Seal – Safeguarding the Saimaa Ringed Seal – Layman’s Report. https://julkaisut.metsa.fi/julkaisut/show/2298

Sarkki, S., Heikkinen, H. I., & Puhakka, R. (2013). Boundary organisations between conservation and development: insights from Oulanka National Park, Finland. World Review of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development, 9(1), 37-63.The Ministry of the Environment and Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (2015). METSO – The Forest Biodiversity Programme for Southern Finland. https://mmm.fi/documents/1410837/1504826/METSO+Factsheet/de777afa-e4b3-475c-8317-747424e2f496/METSO+Factsheet.pdf?t=1443682696000

The DfG course runs for 14 weeks each spring – the 2022 course has now started and runs from 28 Feb to 23 May. It’s an advanced studio course in which students work in multidisciplinary teams to address project briefs commissioned by governmental ministries in Finland. The course proceeds through the spring as a series of teaching modules in which various research and design methods are applied to address the project briefs. Blog posts are written by student groups, in which they share news, experiences and insights from within the course activities and their project development. More information here about the DfG 2022 project briefs. Hold the date for the public online finale online 09:00-12:00 AM (EEST) on Monday 23 May!