This blog post reports on work-in-progress within the DfG course! The post is written by the workstream ‘Elderly Health and Social Care’ dealing with the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health’s brief on ‘Continuity of Knowledge’. The group includes ChinYing Chu from International Design Business Management (Aalto, Art track) program, Ronja Chydenius and Takashige Doi from Collaborative and Industrial Design program (Aalto).

Written by: ChinYing Chu

In response to the aging population and changing social environment, Finland’s healthcare system is undergoing a significant reform. This is a transformation that cannot happen overnight because of the amount of actors and factors involved. With a vision of improving healthcare, for example, Kela (the Social Insurance Institution of Finland) is enhancing OmaKanta, a digital platform that helps citizens access and manage their health information.

However, how should we begin to make sense of such a complex system? Rather than aiming for an instantly actionable solution, our task during this workstream phase is to explore the principles and insights that can guide value-based healthcare with the concept of continuity of knowledge. To do this, we first needed to understand the context, the interplay between national policies and local implementation, public and private healthcare providers, the growing challenges of limited resources and increasing patient needs, challenges of digitalization, etc. As our first step, we focused on elderly health and social care to uncover the hidden gaps and challenges.

Mapping Elderly Care in Finland: Actors, Services, and Data

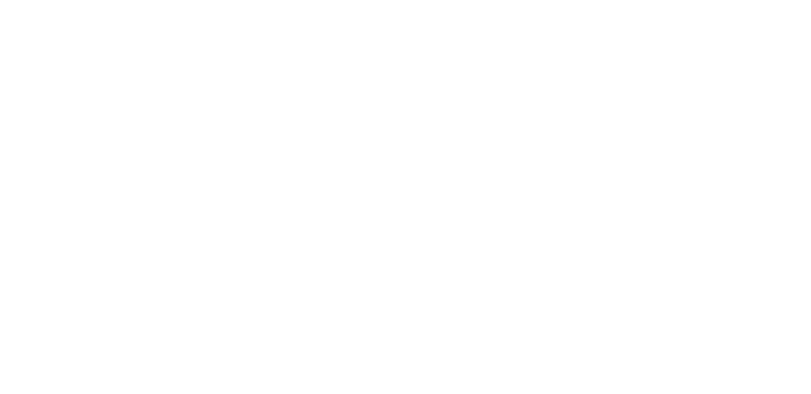

Figure 1: System Map of elderly health and social care in Finland

Who are the actors providing or relating to health and social care services, especially for the elderly? What is the relationship between them? To answer these initial questions emerging in our head, we created a systems map, which shows the actors, the services they provide, and their mutual link. In this map, we use colours and shapes to differentiate services providers and actors in social, living, health, and finance segments. It is noticeable that not all these services are public or private. Some of the service provides are NGOs or religious organizations, such as churches. In addition, we also list the related laws and actions which might influence the implementation. Next, another crucial question appeared. Where is the data, and who owns the data?

Take digital platforms which citizens in Helsinki might use for example, there are Kanta, Apotti (and its portal Maisa), and Omaolo. Kanta is a nation-wide system to record health information, but it doesn’t cover the home care. Maisa, a patient portal integrated with the Apotti system, is used across the Helsinki region to provide citizens access to their health information and services. But it couldn’t be used in other area in Finland. Omaolo is a national online service for social welfare and health care, but it doesn’t cover the home care service either. Even some of the digital platforms cover the same services, but the information might not be shared.

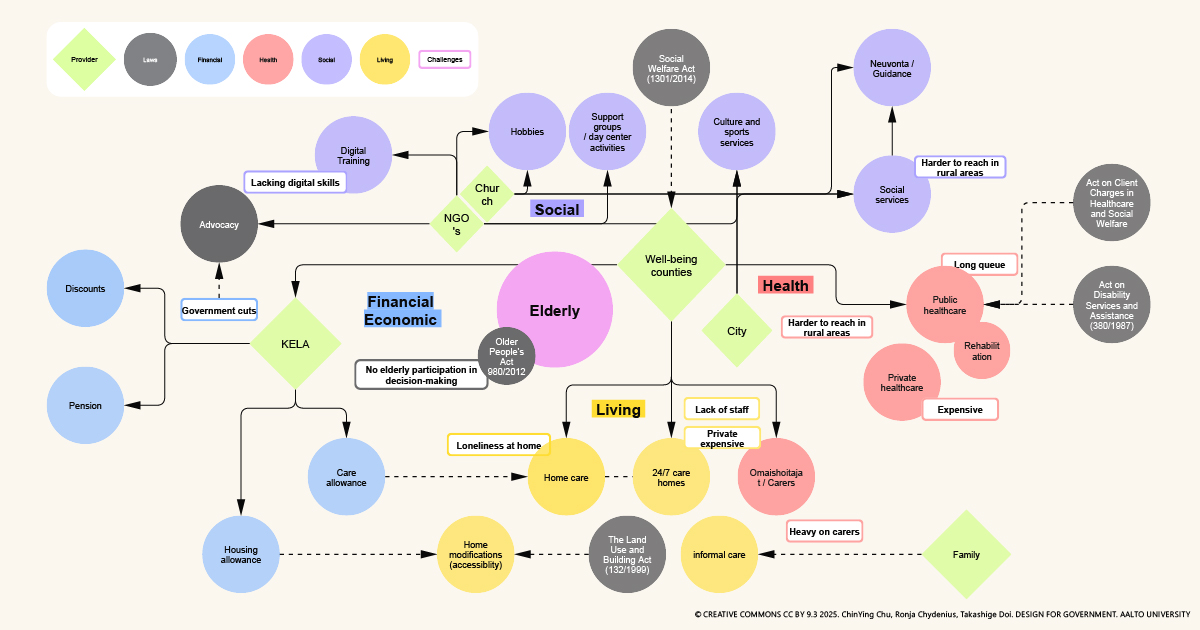

Figure 2: Data covered by services providers

Besides the information in the health and social care institutions, the relate information also exists in private home. In Finland, elderly care has increasingly shifted from institutional settings to home-based and informal care, emphasizing home services and family support over traditional nursing homes (Tuominen et al., 2022). However, do we have any platforms for home carers to record the information?

Living with Disconnected Care

Not all of us experience the Finnish healthcare and social care system as elderly citizens in Finland. To understand the landscape and issues better, we can use a fictional character named Elsa and imagine her day. Elsa, 85, lives alone in Helsinki with multiple health problems. To maintain her independence, she relies on network of healthcare and social services. Home care workers maintain the hygiene, social worker insurance the food is delivered, and doctors oversee the medical treatments. Digital tools such as Apotti, Omaolo, and Kanta help track Elsa’s health information. But these systems do not fully communicate with each other.

As Elsa goes about her day, her health-related data is constantly being updated, but not shard across professionals and platforms. For example, the social worker observes that Elsa has reduced the grocery orders and eat less than before, it could indicate a loss of appetite. The social worker recorded this in the Apotti, but Elsa’s doctor cannot see it in Kanta. The doctor will need to manually request additional information from Elsa. This example shows that the fragmentation of information, which leads to delayed interventions and missed connections. The information is scattered among platforms, and it requires manual updates, duplicated efforts, or even the patient’s own memory to bridge the gap. If we already have digital system, why are we still need elderly (many with cognitive decline) to remember and communicate important health information?

In the Process of Transition, Tension is Everywhere

While mapping out the landscape of elderly health and social care, we also considered what might encourage services providers, include public and private to share their data. However, health data sharing involves multiple stakeholders, each with different interests. This creates tensions in balancing privacy, access, and commercialization (Wang et al., 2024). Without clear incentives and shared frameworks, data remains siloed and limits care coordination.

Navigating Finland’s evolving healthcare landscape is like balancing on a tightrope. Every adjustment requires careful consideration to maintain stability. On one hand, we have urgent need to reform the elderly health and social care system. On the other hand, we need to maintain the privacy, security and the interests among various stakeholders. The question is: how can we keep this balance without tipping too far in either direction? The path forward is not simple, but we will keep exploring! Stay tuned for our journey!

Figure 3: We are working in process!

Reference

Wang, F., Mohamed, M., Ahokangas, P., & Karppinen, P. (2024). Balancing stakeholder interests and paradoxes in health data sharing within health ecosystems. Finnish Journal of eHealth and eWelfare, 16(1), 6-22.

Tuominen, K., Pietilä, I., Jylhä, M., & Pirhonen, J. (2022). A home, an institution and a community–frames of social relationships and interaction in assisted living. International Journal of Ageing and Later Life, 16(1), 49-73.

The DfG course runs for 14 weeks each spring – the 2025 course has now started and runs from 24th Feb to 27th May. It’s an advanced studio course in which students work in multidisciplinary teams to address project briefs commissioned by governmental ministries in Finland. The course proceeds through the spring as a series of teaching modules in which various research and design methods are applied to address the project briefs. Blog posts are written by student groups, in which they share news, experiences and insights from within the course activities and their project development. More information here about the DfG 2025 project briefs. Hold the date for the public finale on Tuesday 27th May!