This blog post reports on work-in-progress within the DfG course! The post is written by group 1B dealing with the Ministry of Environment’s brief on ‘Biodiversity Policy Coherence’. The group includes Annu Mathew from the Collaborative and Industrial Design program and Jing Luo, Jamie Smyth, and Elli Törnqvist from the Creative Sustainability program.

Written by Elli Törnqvist

When we embarked on our journey into the world of biodiversity policy coherence, we had little idea of what was to come. The maze that is the Finnish government and inside it the Ministry of Environment seemed overwhelmingly complicated and difficult to grasp. Similar feelings surrounded policy coherence. After the first weeks of desk research, the round table, and the first interviews, we became more familiar with the questions we should be asking and formed our research agenda. We then began our intense primary research and took in as much information as possible during the next three weeks. It quickly became evident that we are working in a realm of human experiences. Behind all policies are people who are affected by dynamics, interaction, and feelings. Understanding the system from this perspective is crucial for us in the process of creating something meaningful that can drive better biodiversity policy coherence.

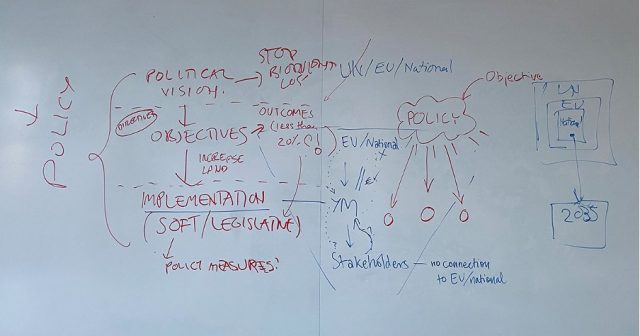

Figure 1. Policy was challenging for us to grasp, but with tools like visualization we could develop a shared understanding for our research. © Creative Commons CC by 4.0 2024. Jing Luo, Annu Mathew, Jamie Smyth, Elli Törnqvist. Design for Government. Aalto University.

Drowning in Work

As the research phase intensified, we kept telling our friends, “Sorry, I’m busy having a meeting at the Ministry of Environment.” How cool is that?! We interviewed civil servants at the ministry as well as experts at SYKE, Motiva and Metsähallitus, which work closely with the ministry. One of our key findings was that civil servants in the Department of Built Environment are in a tricky situation regarding biodiversity since the department’s work on construction and urban planning can contradict it.

Our interviewee from the department, a senior specialist, expressed a deep passion for biodiversity. We could sense the frustration of wanting to do so much more in an environment where non-biodiversity projects pile up on one’s desk. With constant hurry, it is no wonder that considering biodiversity in a construction project feels impossible. However, we recognize this as an important area of interest to us since, for example, Rakennusteollisuus RT recognizes the construction sector’s holistic impact on biodiversity in their Biodiversity Roadmap 2030 (2023).

Most of our other interviewees also mentioned the lack of resources such as time and money in the ministry to do as much for biodiversity as they would like to. The reality of a civil servant is hectic with more work constantly thrown on one’s desk. There doesn’t seem to be enough time to even discuss biodiversity, let alone work on collectively, coherently, and comprehensively. It can easily feel like another additional task to get done.

Figure 2. Ready to interview at the ministry! From left to right: Jamie, Annu, Jing and Elli from 1B and Jandi from group 1C. © Creative Commons CC by 4.0 2024. Jing Luo, Annu Mathew, Jamie Smyth, Elli Törnqvist. Design for Government. Aalto University.

Looking for the Why

As we were finalizing our research, we got to play detectives. With our data on post-its and red thread across the board, we began to form insights from everything we had learned during 11 interviews and weeks of desk research. To support the process, we also drew multiple iterations of a system map, which ended up a fruitful source of more insights. After wrecking our brains in the extremely complex system of biodiversity policy from the perspective of the Ministry of Environment, it became evident that Simon Sinek (2009) was right: start with why.

We discovered in our very first interview with a senior specialist at the Prime Minister’s Office that the loss of “why?” from international agreements and EU policy to the national and local level can be a deadly obstacle to working cohesively towards these shared goals. Here, at the end of our research, we found ourselves staring at the same problem on the map. According to one of our interviewees from the ministry, sometimes the disconnection even happens inside the Finnish government. The Prime Minister’s Office might set objectives for a policy and dump them in the ministry for civil servants to figure out how to achieve them. If the objectives of working collectively are lost when policy trickles down to the ministry, how can one expect civil servants and the ministry as an organization to work cohesively, let alone find meaningfulness in it?

Figure 3. Mapping the system was both fun and informative. © Creative Commons CC by 4.0 2024. Jing Luo, Annu Mathew, Jamie Smyth, Elli Törnqvist. Design for Government. Aalto University.

The Psychological Game of Democracy

“It’s been a difficult year at the ministry,” sighed one of our partners after our midterm presentation. Many of our stakeholders from the ministry and the Prime Minister’s Office gathered on Aalto campus, where we presented our progress, research, and main findings. In our interviews, we found that political forces and the 4-year governmental cycle hinder biodiversity policy coherence. The reallocation of resources and change of priorities disrupt ongoing efforts to save the environment our own existence so strongly relies on. A civil servant in communications of the ministry revealed that biodiversity being lower on the current government’s agenda interrupts their biodiversity work. Meanwhile, our interviewee from the Prime Minister’s office pointed out that it can take decades of work to change the state of biodiversity.

However, the 4-year cycle is also called democracy, which we strongly believe in. But it is true that the planet urgently needs coherent biodiversity action. The discontinuity is also a type of psychological challenge to civil servants since it entails frequent uncertainty about the future of biodiversity action – of the projects and policies they pour their sweat and tears into. One motivation for our design project is to create something that gives the civil servants, who we have been lucky to get to know, hope in the occasionally hostile environment. Because if these motivated and passionate defenders of biodiversity are stripped of belief and motivation, who is there left to enable policy coherence?

Eyes on Opportunities

After research, analysis, and insights, our team is ready to dive into a sea of opportunities where we will begin the process towards a proposal in collaboration with our partners. It has become clear that the solution is not to simply slap on more collaboration to achieve coherence. Our research on the realities of work at the ministry has given us valuable insights into barriers and constraints that disrupt biodiversity policy coherence. Stay tuned for what happens next!

References

Rakennusteollisuus RT. (2023) Rakennusalan biodiversiteettitiekartta 2030. Helsinki: Rakennusteollisuus RT.

Sinek, S. (2009) Start with Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action. New York: Portfolio.

The DfG course runs for 14 weeks each spring – the 2024 course has now started and runs from 26 Feb to 29 May. It’s an advanced studio course in which students work in multidisciplinary teams to address project briefs commissioned by governmental ministries in Finland. The course proceeds through the spring as a series of teaching modules in which various research and design methods are applied to address the project briefs. Blog posts are written by student groups, in which they share news, experiences and insights from within the course activities and their project development. More information here about the DfG 2024 project briefs. Hold the date for the public finale on Wednesday 29 May!