These blog posts report on work-in-progress within the DfG course! The posts are written by groups dealing with the Ministry of Interior’s brief on ‘Strategy for expatriate Finns’.

—

Group 3B: Amir Tahvonen and Savannah Vize from Creative Sustainability, and Hannah Roche and Shuaijun Zhang from Collaborative and Industrial Design.

Defining an intervention: Looking for leverage points, framing a solution

Weeks five to eight in our design process were dedicated to bridging the gap from research to practice, framing our solution type, and finding a space for it. This phase also includes keeping in touch with our stakeholders and gathering their feedback on our direction. Next week, we’re hosting a workshop and assisting in another, and are meeting with some of our primary stakeholders to ideate this week.

It was (and is) a challenge to bring the concept of leverage points in an understandable, practical and usable way into the casework. We are still struggling to find the suitable point(s) where a change would make a good impact. To familiarize ourselves with possible interventions, we were introduced to a host of examples described as nudges – different changes that are directed to alter human behaviour. Thaler et al. (2013) describe the importance of designing for humans who err, make irrational choices, follow others, make up their minds with limited information or are overwhelmed by it, and introduce methods to make more human-minded products, services, paths, and maybe even policies.

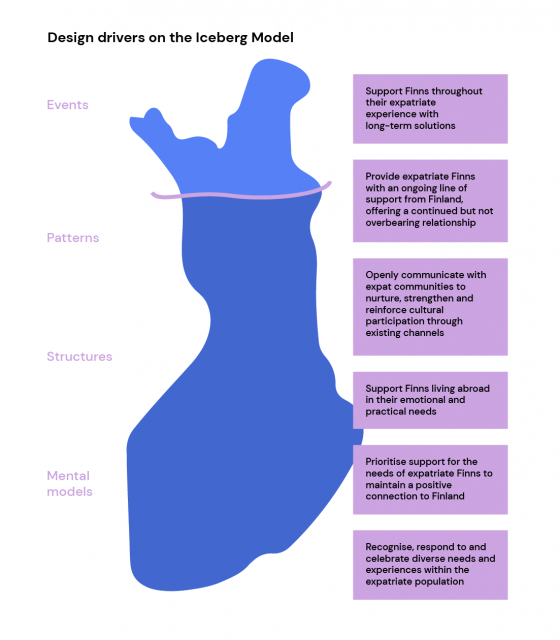

Prompted by the beautiful iceberg model drafted by Group 1B in their Mid-Term presentation, we mapped some of our insights on the iceberg model to see what they would be at depth, and our mapping indicated that the experience of some Finns living abroad of not being included might be caused by difficult emotions like suspicion and fear. We continued using the iceberg model as a tool to check where our design drivers (guiding principles our ideas and solutions should follow) would be located.

At this point, our focus seems to be on finding ways in which policy writing could be better informed by the human insights found by qualitative research methods. Our thinking is that if the policy could be written in a human-centered way, or with these insights in mind, the policies themselves might then actualize into implementations that would better serve the Finnish diaspora and improve the experiences of Finns living abroad. This is a broad, sweeping generalisation though, and might not prove to work in practice.

To see where the insights could help and inform, we are mapping out the process of policy writing. Nothing is definite – we are still keeping the level of implementation open in case we find out that the policy writing process is not a suitable place for intervention.

Keeping sustainability in the frame

With all of these nudges, drivers, and behavioural insights, ecological sustainability seems to have gone a bit out of the frame. This highlights the importance of keeping it in the design process, in our graphs, and in our considerations. In 2017, the emissions caused by flight for an average Finn accounted for 13% of their mobility emissions, while the total mobility emissions were 27% – nearly 3000 kg CO2e – of the whole carbon footprint (IGES, 2019).

Since Finland is aiming for carbon neutrality by 2035 (Valtioneuvosto, n.d.), the different emission reduction potentials for mobility and other lifestyle sectors can’t be left unaddressed. There are direct emissions related to moving by flight, car, or train, and these differ depending on e.g. the distance. In addition, there can be emissions related to moving luggage or furniture in more permanent situations or the acquiring of such in the destination location, and of course lifestyle emission once there – driving, eating, heating, living. Research into these impacts is a complex topic on its own, but they should be held in mind.

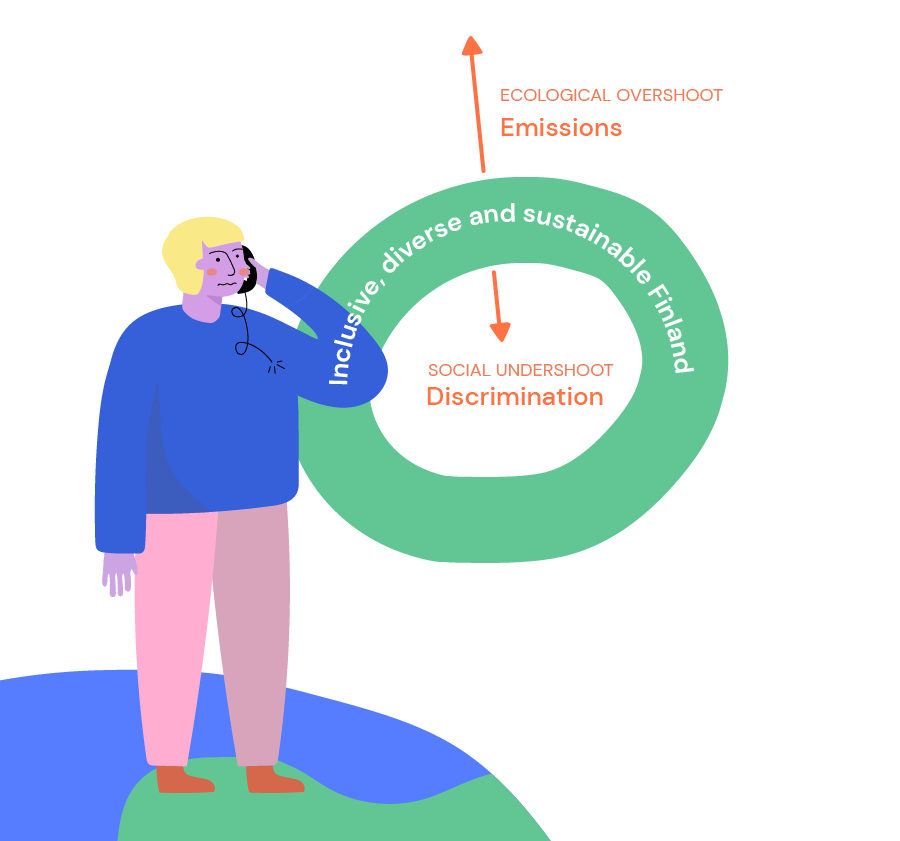

If the whole migration process of Finns is seen as a modified, simplified doughnut model (Raworth, 2017), in addition to the overshoot of planetary boundaries it is clear from our research that a social undershoot is experienced by some Finns with more diverse roots and nationalities – the goal of inclusive and diverse Finland is not yet met. An ideal situation could be one where ‘Finnish’ would be understood more broadly so that more people could feel at home in Finland wherever they might be staying. This is reflected in one of our design drivers: ‘Recognise, respond to and celebrate diverse needs and experiences within the expatriate population’. This, ultimately, could be the aim of our intervention as well.

References:

IGES, Aalto University & D-mat ltd. (2019). 1.5-Degree Lifestyles: Targets and Options for Reducing Lifestyle Carbon Footprints. Technical Report. Institute for Global Environmental Strategies, Hayama, Japan. https://www.iges.or.jp/en/pub/15-degrees-lifestyles-2019/en

Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut economics: seven ways to think like a 21st century economist. Random House Business Books.

Thaler, R. H., Sunstein, C. R., Balz, J. P. (2013). Choice Architecture. In Shafir, E. (Ed.), The behavioral foundations of public policy (pp. 428–439). Princeton University Press. https:// https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400845347

Valtioneuvosto. (n.d.). Government Programme: Strategic Themes. https://valtioneuvosto.fi/en/marin/government-programme/strategic-themes

—

Group 3C: Phuong Nguyen from the New Media Design program, Mõtus Lõmaš Kama from Collaborative and Industrial Design program (Exchange), Mariela Urra Schiaffino, Creative Sustainability program (Design track), and Nicholas Colb from Information Networks program.

Facing the wall and embracing complexity – step-by-step towards the solution space

This blog post gives an overview of our teams’ progress over the past four weeks. Since the last post, we have moved out of our research phase and concentrated on developing our solution. We started narrowing our scope by defining design drivers and leverage points, and are now looking at potential design interventions. However, it hasn’t been all that smooth…

After the mid-term review, we defined our direction as connecting and empowering young Finnish expatriates through supporting inclusive opportunities for participation. With this focus in mind, we analysed and iterated our systems map and expatriate journey (introduced in the previous post). Through this, it got clearer that our target group – young expatriates obtaining higher education or starting their career – is most distant from existing means of participation and thus Finland in general.

Through the past weeks, we have also been actively in touch with various stakeholders together with our supergroup. Having online meetings with representatives of Suomi-Seura and the Ministry of Interior has given us insight into existing solutions and networks for expatriates and also how our concepts could support policymaking.

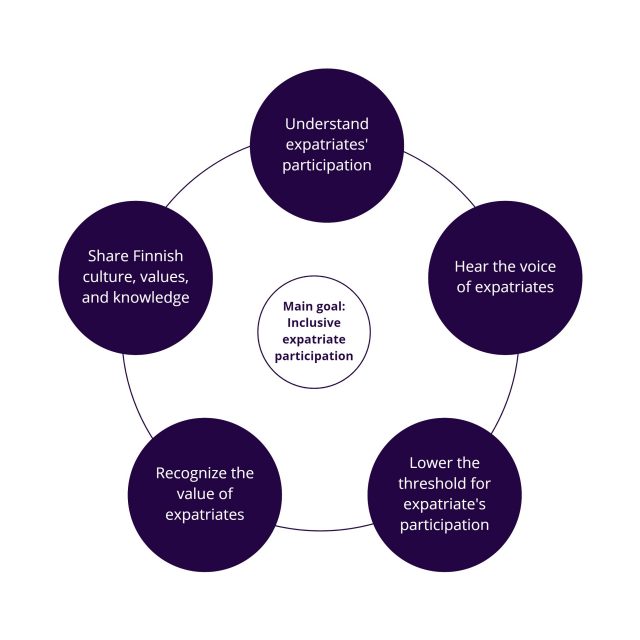

Based on our research and analysis we developed design drivers – “principles and directions for ideation” (Heinonen, lecture) – which help guide us in the concept development phase. Our initial ideas were categorized into seven themes covering a total of fourteen drivers. To identify the themes and directions with the most untapped potential, we then narrowed it down through cross-referencing the drivers with the old Strategy for Expatriate Finns and comparing them with our Expatriate Journey Map. This left us with one overarching theme which covers five drivers:

While most drivers seem quite tangible, the most complex (and possibly most important) driver here is “Understand expatriates’ participation”. Participation is multifaceted – understanding expatriates’ definition of it can help develop relevant participatory means supporting expatriates’ lives and connecting them with Finnish networks. The other drivers imply rather straightforward changes, giving more value to the expatriates and empowering them through making participation more accessible.

After the initial progress and having the one-week break, our team got stuck. We were in the middle of many ongoing processes and progressing without reaching any tangible milestones. Staring at our research data, insights, and design drivers without understanding what to do with it we felt like we were facing a wall. Being stuck like this can be quite discouraging and that slowed our momentum. During one of our feedback sessions, we were reminded that being stuck is okay and the wall of confusion should be embraced, maybe even celebrated. Getting stuck is a common situation in a design process but it is easy to forget that. In the past few days, however, we have started to see light again.

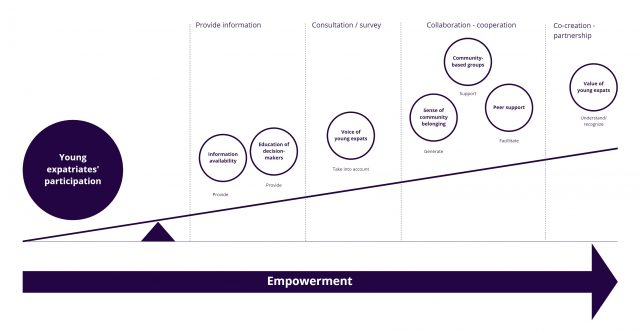

Leaning on the drivers and research data we sought leverage points – “places in the system where a small change could lead to a large shift in behavior” (Meadows, 1999) to see where our concepts could have the most impact. For this, we analysed different parts in the Expatriate Journey to understand trigger moments – what are the critical events where expatriates are more connected or lose their contact with Finland. We learned that expatriates often lose contact with Finland soon after graduating Suomi-Koulu (Finnish Schools) and often don’t reach it again before older age and reaching out to the Suomi-Seura (Finland Society). This was also confirmed during the meetings with stakeholders. As such, moments of losing or re-establishing contact could potentially function as leverage points.

The leverage points presented here are still quite abstract so we are continuing on defining them. However, the model clearly indicates the relevance of recognizing the value and input of expatriates themselves.

Our goal for the deliverables will be developing a concept that could help the Strategy for Expatriate Finns support a more inclusive participation system. One option could be providing a “framework for inclusive participation for expatriate Finns” to the Ministry of the Interior. Another thing we still need to address is looking for ways to monitor the implementation of changes and getting feedback from expatriates living abroad. The old Expatriate Strategy included no means of monitoring and reflecting so it is hard for the government to evaluate the outcomes of previous policies.

As for now, we are still developing our interventions. To achieve this, we need to classify and frame the types of interventions which would best fit our context. In parallel, we are seeking analogous references and inspirational benchmarks.

In addition, we still need some input from the expatriates to gain more understanding about possible intervention points. With this in mind, we will also be conducting collaborative sessions with expatriates together with team 3B and representatives of Suomi-Seura. One of the main things we aim to uncover with this is how expatriates define participation and how they would like to be connected to Finland.

References:

Heinonen, T. Design drivers, lecture

Meadows, D. H. (1999). Leverage points: Places to intervene in a system.

—

Group 3A: Rūta Šerpytytė and Liisi Wartiainen from Collaborative and Industrial Design program, Chloe Pillon from Creative Sustainability program, and Kaisa-Maria Suomalainen from Future Studies program (University of Turku).

Lost in Transition: How to recognize and leverage the skills of expatriates?

After presenting the results of our research in the Mid-term Review, we put our brief and research work aside and let our learnings sink in. The next task at hand would be deciding the direction of our project and finding the problems worth solving.

During our research phase, we learned that repatriation is not a straightforward process. Our interviewees reported feeling disconnected and facing challenges after returning to Finland. For some, the questions related to identity had become more complex, whereas others had struggled in finding employment.

We decided to focus on the experiences of returned expatriates for three reasons: 1) their needs are relatively unknown, 2) their expertise could be better leveraged 3) integration is crucial if the goal is to attract more expatriates to Finland in the future.

The need for support has also been recognized on governmental level. “Apart from employment there aren’t any integrating services if you’re actually a Finnish citizen returning”, a stakeholder pointed out in one of our discussions. Addressing this group in the new strategy for expatriate Finns is important, and we felt our work could contribute to it.

Starting with appreciation and inclusivity

In addition to services, the returned expatriates have also been lacking a sufficient level of appreciation and understanding of their unique experiences. In the eyes of Finnish employers, international expertise is often a liability instead of an asset.

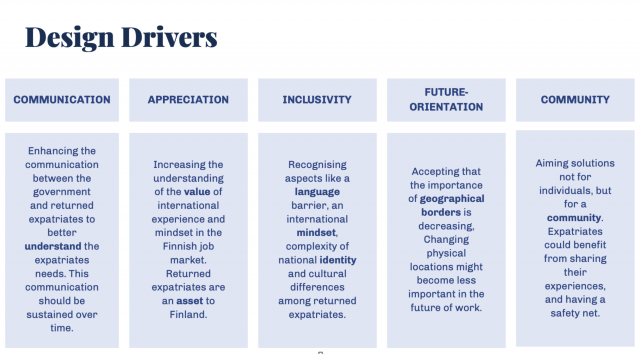

With our design work, we want to improve the recognition of international mindset and skills and increase cultural inclusivity. In an ideal scenario, expatriates should not feel like they must shrink themselves to fit in the Finnish working life and society. As we defined and re-defined our goals, we came up with five key drivers:

Analysing our systems map with fresh eyes

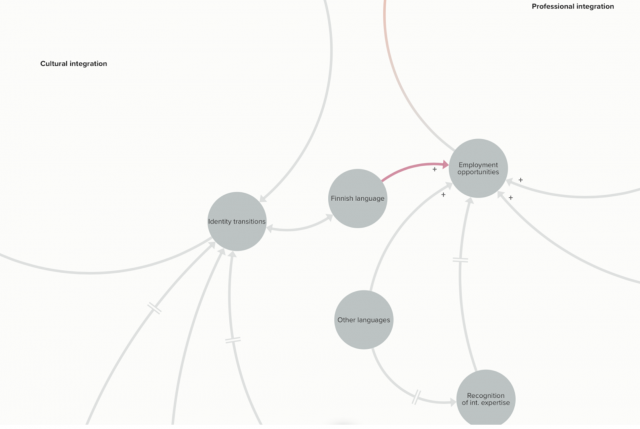

To identify potential leverage points, we revised our systems map and focused on the process of repatriation. On the social level of integration, elements such as family, personal networks, and even memories are important. The process gets more cluttered when transitioning to professional integration. Personal networks, credentials, language skills, and employer needs start to play an important role, and they can either speed up or slow down integration. There are also considerable delays in these feedback loops.

Identity transitions could be essential to cultural integration, and we believe that international or complex national identity slows down the process of cultural integration. For a full view of our systems map, please visit: kumu.io/Liisiw/dfg-team-3a

Focusing on the delays of the system started to make sense, as they could be impactful leverage points (Meadows 2009, 152). Missing links and information links also caught our attention.

Finding where to intervene

After we spotted the most potential leverage points, planning our intervention became significantly easier:

- Knowledge of Finnish culture is a key in cultural integration, yet many returned expatriates are lacking in this area. If the connection could be strengthened, we could improve the integration process.

- Official service channels also lack services that could help with cultural integration. A connection between these elements would have a positive effect on integration.

- Building a new link between informal communities and professional networks could improve employment opportunities

- Recognition of international experience would also support a multitude of national identities. This would foster a sense of belonging without having to give up an identity as an international citizen of the world.

Final stakeholder activities due

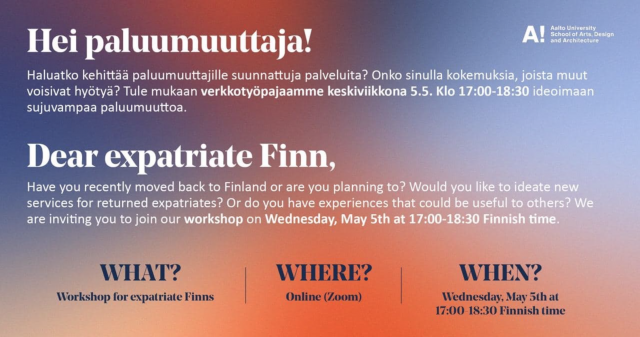

Before we start ideating our solution, there are still two more important stakeholder activities to come. Next week, we are going to run an ideation workshop together with returned expatriates. This opportunity will be used to validate our earlier insights and gather evidence for the direction we have chosen. In addition to this, we have set up a call with an expert from the field of career services. We are looking forward to these events and the last phase of the course when we combine the results of our research and creative thinking to finalize our solution.

Bibliography:

Meadows, Donella (2009). Thinking in Systems. Earthscan: London

—

The DfG course runs for 14 weeks each spring – the 2021 course has now started and runs from 01 Mar to 24 May. It’s an advanced studio course in which students work in multidisciplinary teams to address project briefs commissioned by governmental ministries in Finland. The course proceeds through the spring as a series of teaching modules in which various research and design methods are applied to addressing the project briefs. Blog posts are written by student groups, in which they share news, experiences and insights from within the course activities and their project development. More information here about the DfG 2021 project briefs. Hold the date for the public online finale online 09:00-12:00 AM (EEST) on Monday 24 May!