Written by: Marta Ligaj

In recent years, the Finnish healthcare system has undergone many substantial changes. Most of them were induced by SOTE – a healthcare reform restructuring the system, making care more uniform and accessible (Kangas & Kalliomaa-Puha, 2022). Besides structural iterations, the relationship between doctors and patients also faces a significant shift, as the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health and the Ministry of Finance introduce a General Practitioner model (omalääkäri) promoting consistent access of patients to personally assigned doctors.

From 1972 until 2021, the Finnish healthcare system comprised 309 municipalities. Finally, after almost 50 years it was time for change (Keskimäki, 2022). The Finnish government introduced 21 “’well-being counties” + Helsinki city as new healthcare hubs which “absorbed” the fragmented centres. Apart from extensive structural changes, the relationship between patients and doctors is also underway as a new general practitioner model is being surveyed. If everything goes according to plan, patients can expect to have a 1-on-1 relationship with permanently assigned caretakers.

The healthcare reform – after 16 years of waiting

The talk about the Finnish healthcare reform (SOTE) started in 2005. However, it wasn’t until June 2021 that the bill was approved, as stated by the European Social Policy Network (Kangas & Kalliomaa-Puha, 2022) . For sixteen years the reform has been a “ping-pong ball” passed between five Finnish governments as disagreements about its implementation were piling up. The core idea of the reform was to establish 22 “well-being service counties” in Finland that would replace the current, fragmented system (Finland’s Health and Social Services Reform, 2022). The primary goals of the reform are to grant equal access to healthcare, ensure a high standard of care practices and improve the availability of healthcare services. Nevertheless, the fundamental reason for the reform doesn’t stop at virtuous ambitions such as equality; in fact, currently, the current healthcare system cannot be financially sustained. Why is that? The answer is rather simple – like many European countries, Finland is facing the challenges of an increasingly ageing population. More people are retiring, and fewer citizens are of working age, which inflicts a decline in the tax revenue. Nota bene, the former healthcare system derived its revenue from taxes and faced progressively severe underfunding. To address that issue, the SOTE reform introduced a healthcare system with a different primary source of income – “Imputed and block central government financing” (Finland’s Health and Social Services Reform, 2022). Despite the reform being a necessary step to saving the prosperity of the healthcare system it has been criticized by some Finnish parties for its poorly predicted costs. Moreover, some raised concerns about the new system’s “excessive reliance on public sector service providers” and the negligence of private health and social care sectors (Kangas & Kalliomaa-Puha, 2022).

New patient-doctor relationship

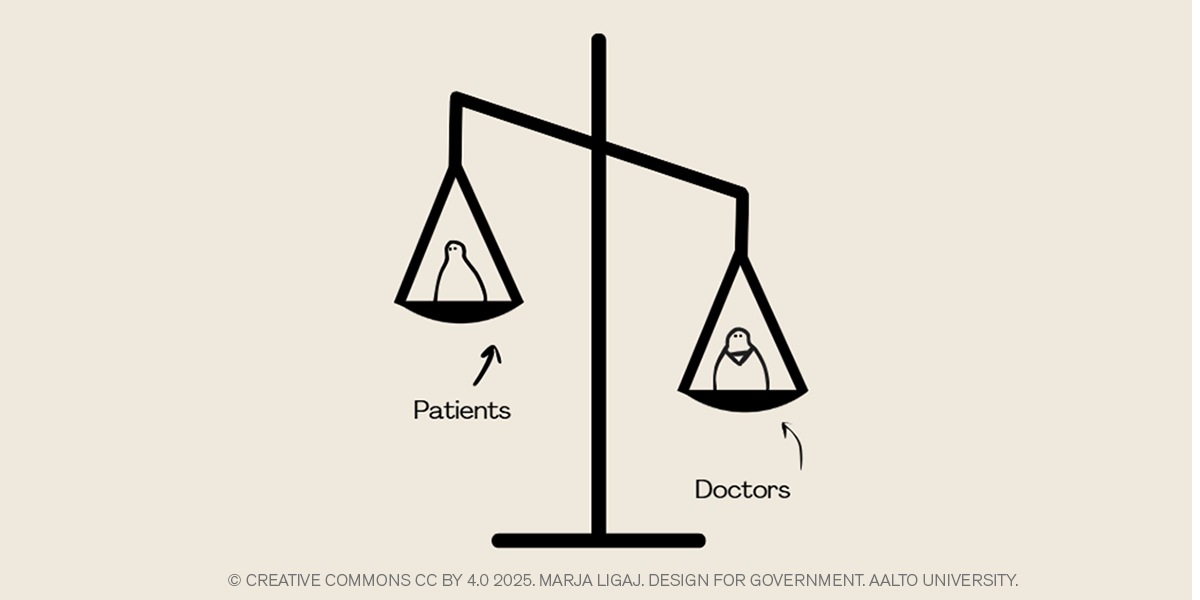

Despite SOTE being the major recent change in the Finnish healthcare system, it is not the only one. That is, besides the reform, a new healthcare model of the patient-doctor relationship has been proposed by The Ministry of Social Affairs and Health and the Ministry of Finance. The model is called a “general practitioner” model and focuses on the continuity of care. In other words, it relies on the patient being assigned to a dedicated nurse as their first point of contact. This model hopes to achieve higher rates of patient satisfaction and faster recovery time (Omalääkäriohjelman Johtoryhmä Asetettu – Sosiaali- Ja Terveysministeriö, 2025). Additionally, the general practitioner model has been proven to: improve the quality of care, decrease significantly morbidity and mortality and reduce overall need for healthcare services and their costs (Auvinen et al., 2021). In essence, it simplifies the process of obtaining care by avoiding the unnecessary distress of being referred to a new doctor every time. It allows patients to familiarize themselves with the caretaker and vice versa. This idea seems to be positive on many levels, yet it hasn’t evaded critique. For instance, Sally Leskinen, head of the South Karelia welfare area states that the shortage of doctors in Finland makes the plan impossible to implement (Haapanen, 2024). Despite concerns being raised, The Ministry of Social Affairs and Health and the Ministry of Finance have already started promoting the new program. The “trial period” for the general practitioner model started in November 2024 and is intended to end in April 2027.

What if?

The Sote reform, as well as the general-practitioner model, share a common goal – improving the quality of care for patients. Accordingly, many articles cited in this blog emphasize the positive impact of the above changes on care-receivers. But one question prevails; what about caregivers? Taking into account the shortages of medical staff and underfunding of the healthcare sector, it seems important to acknowledge the challenges experienced by doctors who make the system. Unfortunately, the SOTE reform seems to overlook the importance of private and social care providers (Finland’s Health and Social Services Reform, 2022), while the new general practitioner model could prove unrealistic due to staff shortages (Haapanen, 2024). In pursuit of the ideal healthcare model, both the reform and the new patient-doctor model could be at risk of putting too much pressure on medical staff. Therefore, while the changes in Finnish healthcare are necessary and important, they could be introduced more mindfully with respect towards medical staff. If they fail to do so, it would only be natural for doctors to feel discouraged from pursuing their work – and we can’t have that.

References:

Auvinen, J., Tuompo, W., Riekki, M., Timonen, M., & Eskola, P. (2021). Hoidon jatkuvuusmalli.

Omalääkäri 2.0 -selvityksen loppuraportti. Sosiaali- ja terveysministeriön raportteja ja muistioita.

Haapanen, M. (2024, November 20). Omalääkärimallille kovaa kritiikkiä: Lääkäreitä ei riitä kaikille, varoittaa Etelä-Karjalan hyvinvointialuejo… Yle Uutiset. https://yle.fi/a/74-20125765

Kangas, O., & Kalliomaa-Puha, L. (2022). Finland finalises its largest-ever social and healthcare reform. European Social Policy Network.

Keskimaki, I. (2022). Development of Primary Health Care in Finland. The Lancet Global Health Commission on Financing Primary Healthcare.

Omalääkäriohjelman johtoryhmä asetettu – Sosiaali- ja terveysministeriö. (2025, January 21). Sosiaali- Ja Terveysministeriö. https://stm.fi/-/omalaakariohjelman-johtoryhma-asetettu

Finland’s health and social services reform. (2022). Association of Finnish Municipalities.

The DfG course runs for 14 weeks each spring – the 2025 course has now started and runs from 24th Feb to 27th May. It’s an advanced studio course in which students work in multidisciplinary teams to address project briefs commissioned by governmental ministries in Finland. The course proceeds through the spring as a series of teaching modules in which various research and design methods are applied to address the project briefs. Blog posts are written by student groups, in which they share news, experiences and insights from within the course activities and their project development. More information here about the DfG 2025 project briefs. Hold the date for the public finale on Tuesday 27th May!