This blog post reports on work-in-progress within the Aalto Design for Government (DfG) course! The post is written by the workstream of Aging Population and Public Services, dealing with Kela, the Social Insurance Institution of Finland’s brief on ‘Continuity of Knowledge’ in healthcare reform. The group includes Paola Rapino from Creative Sustainability (Aalto, Exchange), Huang Tzu-Tai from Sustainable Entrepreneurship (Aalto), and me, Yuchen Tang from Collaborative & Industrial Design (Aalto).

Written by: Yuchen Tang

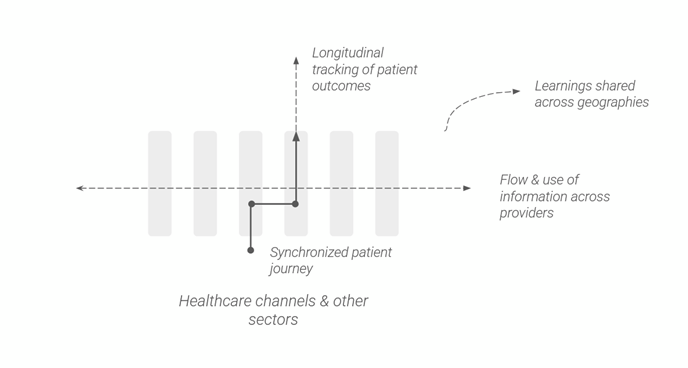

This year, one of the two briefs at the Aalto Design for Government course continues on the theme of ‘continuity of care’ in Finnish healthcare reform, a collaboration with Kela, the Social Insurance Institution of Finland. The hallmarks of a continuity of care model is a healthcare system that synchronizes healthcare delivery as patients move through healthcare channels by retaining ‘collective memory’ of the patient’s treatment journey, tracks end-to-end patient outcomes, provides designated healthcare contacts and enables proactive management. The availability of information is a key enabler to delivering continuity of care, and this year our brief partner Kela asks: how can the ‘continuity of knowledge’ across organizations and users support more effective delivery of continuity of care?

On briefs such as these, my inevitable feeling is always one of overwhelm and then dread. How does one make sense of, let alone work on a system as complex as healthcare? And what can design students possibly do? Despite the apprehension, this was the role of design I wanted to find out.

Over the past three weeks, I am beginning to see how these questions can be approached, and the value of a design perspective in these strategic challenges. Here I want to share some learnings of the approach we took, our preliminary sensemaking of the issues, and my answer thus far to the role of design. Firstly, some background.

Background

Finnish healthcare has been described to be in ‘crisis’, with rising costs without improvements in outcomes, long patient queues, discontinuities in care, including lacking a personal doctor model, and is in a financially and socially unsustainable state (Eskola et al., 2022). Compounding this is the looming issue of an aging population. Finland is already the third oldest population in the world, with a dependency ratio that will continue to rise and bear serious implications on the economy and tax base (Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, 2020).

In response, a continuity of care (COC) model of healthcare has been proposed in the Finnish government agenda since at least 2019 (ibid.). The consensus around COC is it decreases healthcare costs by improving overall healthcare outcomes. Continuity of care has no agreed upon definition, but is typically categorized along three dimensions. As relational continuity, it refers to an on-going relationship between patient and designated healthcare staff, who brings long-term tacit, cultural, personal knowledge of the patient and connects them into the larger healthcare system. As information continuity, it refers to the availability of information across providers and tracking patient outcomes overtime. As management continuity, it includes the coordination of case management and care planning across providers and sectors (World Health Organization, 2018; Ljungholm et al., 2022).

In 2023, the Finnish Government implemented the SOTE reform to healthcare, merging healthcare services from 309 municipalities into 21 Wellbeing Service Counties and Helsinki. The aim was to improve healthcare integration, increase risk-pooling, and thereby decrease barriers to continuity of care (Kungas & Kalliomaa-Puha, 2022). In short, Finland’s transition towards a continuity of care model is just beginning.

Figure 1 Author visualization of continuity of care, inspired from World Health Organization (2018).

© CREATIVE COMMONS CC BY 4.0 2025. YUCHEN TANG. DESIGN FOR GOVERNMENT. AALTO UNIVERSITY.

Learning 1: Getting Started & Collective Sense Making

There is perhaps no way around the initial confusion and discomfort in becoming acquainted with a complex topic. This is perhaps the hard work that must be done for us to begin to work on important issues. However, now having gone through it once, a few things might make it easier in the future.

Having (and revealing) a framework to structure the dizzying array of information can help begin revealing connections and concepts. What exactly is continuity of care, continuity of knowledge, value-based healthcare, aging populations, SOTE healthcare reform, and how do they all connect? While designers may be used to graphical information, I find few things convey the same clarity as text. Similarly, when a task as complex as understanding a healthcare system is divided into workstreams (as reasonably should), it helps to have a framework or a central narrative for the team to align around to confirm and debate understanding.

Figure 2 Supergroup workboard, while the volume of information is great, the lack of an overall framework makes it difficult to understand the broader picture.

© CREATIVE COMMONS CC BY 4.0 2025. YUCHEN TANG. DESIGN FOR GOVERNMENT. AALTO UNIVERSITY.

Learning 2: Aging Population & Increasing Importance of Continuity of Knowledge

My workstream’s focus was on ‘aging populations and its connection to continuity of knowledge’. Yet, what was the connection? If continuity of knowledge should be the basis of any well-functioning healthcare system, why should it matter that the population is aging? I only made the connection when I realized that part of continuity of knowledge is tracking end-to-end health outcomes over tracking volume of healthcare activity. While population health may now proximately correlate with the volume of healthcare activity, this is likely to become less suitable for an aging population, simply because medical procedures for the elderly are less likely to produce the same degree of benefits as for the young.

To maintain trust and well-being of an aging population then, it is imperative that a form of continuity of knowledge – in the sense of outcomes measured, becomes the indicator. And being an outcomes-level indicator, it can lead to broader considerations of health drivers, such as social determinants which become increasingly important in old age.

Learning 3: Design Value to Complex Challenges – A Design Mindset

The value of design to complex challenges for me thus far, is not in the usual design methods of journey maps, diagraming or design thinking. It is in the design mindset of employing a strategic look to all the components of the issue and proposing new sets of ‘what might be possible’. This is an approach that can just as well be adopted by non-designers. As Roger Martin (2009, 2020) puts it, design’s abductive logic is a counterbalance to the operating logic of ‘reliability’, where action is informed by largely what currently exists and what is reliably known.

In a world where change is exponential, the benefit of relying solely on what is ‘reliably known’ is diminishing. Our professor Marco Steinberg notes, where no past data exists or remains valid for future interpolation, the ability to ‘feel’ our way forward becomes vitally important. An aging population on the scale that is to come is not something the world has encountered, and will require new ways for healthcare to act. The alternative to adaptation is the governmental tendency to cut services to maintain costs and to rely on old structures, rather than thinking of new ways of value creation.

References

Esokla et al. (2022). Continuity of Care Model: Final Report of the Omalaikaari 2.0 Survey. Reports and memoranda from the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health 2022:17. Retrieved March 11, 2025 from https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/handle/10024/164291

Kungas, O. & Kalliomma-Puha, L. (2022). Finland finalises its largest-ever social and healthcare reform. European Social Policy Network. Retrieved March 11, 2025 from https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=25947&langId=en

Ljungholm, L., Edin-Liljegren, A., Ekstedt, M., & Klinga, C. (2022). What is needed for continuity of care and how can we achieve it? Perceptions among multiprofessionals on the chronic care trajectory. BMC health services research, 22(1), 686.

Martin, R. (2009). What is Design Thinking Anyway? Harvard Business Press. Retrieved March 11, 2025 from https://designopendata.wordpress.com/portfolio/what-is-design-thinking-anyway-2009-roger-martin/

Martin, R. (2020). Roger Martin on leveraging design in business. [Video]. Design Indaba. Retrieved March 11, 2025 from

The DfG course runs for 14 weeks each spring – the 2025 course has now started and runs from 24th Feb to 27th May. It’s an advanced studio course in which students work in multidisciplinary teams to address project briefs commissioned by governmental ministries in Finland. The course proceeds through the spring as a series of teaching modules in which various research and design methods are applied to address the project briefs. Blog posts are written by student groups, in which they share news, experiences and insights from within the course activities and their project development. More information here about the DfG 2025 project briefs. Hold the date for the public finale on Tuesday 27th May!