This blog post reports on work-in-progress within the DfG course! The post is written by group C1 dealing with the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, specifically KELA’s (Social Insurance Institution) brief on ‘Continuity of knowledge’. The group includes Francesca Martini and Paola Rapino from the Creative Sustainability program, Joni Lappalainen and Takashige Doi from the Collaborative and Industrial Design program, and Huang Tzu-Tai from the Sustainable Entrepreneurship program at Aalto University.

Written by: Francesca Martini

Setting the stage for change

How can words and visuals shift a national care system? For the past three months, our team has been understanding the care system in Finland, identifying gaps and key areas of improvement. Since early April, we’ve moved from fieldwork and systems analysis into the final stage of our project: crafting and presenting a proposal to our partners. Our goal is to influence how continuity of knowledge [1] can be strengthened in elderly care through design-driven policy suggestions. This involves defining a narrative that promotes a specific vision for how the system could be, as well as potential ways to achieve it (based on our insights — of course!). In the following post I will reflect on the power of narrative to trigger behavioral, societal, and institutional shifts, the role that design plays in this, and what our vision for care is.

[1] By continuity of knowledge, we mean more than just data sharing—it’s about ensuring that medical, social, and personal information flows meaningfully between people and systems, helping improve care decisions and outcomes.

The value of narrative and design to trigger shifts

Communication is key for many aspects in life. In the context of government, it is especially relevant to convince, mobilize and to actively set an agenda. Here is where design can play a valuable role, because not only are we trained to be good storytellers, but we also have the power of creating visuals that support our narrative. As Ezio Manzini, a leading scholar in design for social innovation, puts it: “Designers can act as sense-makers, helping to give shape to shared visions and to make them visible, discussable, and actionable.” (Manzini, 2015, p. 52)

As a strategic designer, I’ve been challenged throughout my whole career in creating narratives, but mainly for private organizations. In this project, I had to think on an even higher level, addressing changes that need to occur on a national level, involving every citizen (or at least the seniors). In our project, narrative is key to communicating our proposal—helping partners see what needs to change, sparking empathy, and inspiring action. Rather than setting a fixed plan, it offers starting points and a shared direction to support building an agenda around continuity of knowledge in care.

Figure 1 (Vision): Care doesn’t happen exclusively in the hospital—it unfolds in everyday routines and relationships. This image captures our vision for community-based, human-centered care.

Shifting the focus: from reactive to preventive care

What are we proposing? A shift in the care system: moving from reactive responses to proactive, preventive care. Our vision is that care doesn’t—and shouldn’t—happen exclusively in the hospital. It happens in people’s everyday lives. We believe care should be:

-

Based on human interaction,

-

Preventive, holistic, and integrated across health and social domains, and

-

Supported by digital tools—but not defined by them.

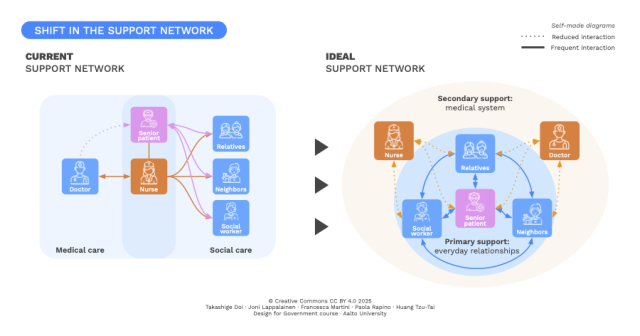

To reach this vision, we looked at the patient’s broader support network. In addition to doctors and nurses, people are surrounded by social workers, neighbors, and relatives. Together, they hold valuable, often overlooked knowledge about a person’s well-being.

Today, the formal care system typically steps in only once a clear health issue appears. But what if we could involve this wider network earlier, before things escalate? While informal actors may already be present, their role is often limited or disconnected from the care process. Social relationships are not just supportive—they’re essential. As Holt-Lunstad et al. (2010) found, strong social ties increase survival likelihood by 50%.

This importance of human connection was also emphasized in our fieldwork. One nurse told us, “Elderly people stay sharper when they’re around others” (Nurse 3, interviews). Another explained, “The nurse-patient relationship may be the only human contact the patient has. Social interaction must be prioritized. It also makes the work easier—patients cooperate more when they’re engaged” (Nurse 5, interviews).

Figure 2. (Support network shift): These diagrams compare the current support network—centered around the nurse’s role—with our proposed shift, which places everyday relationships at the core of preventive support for seniors.

Seeing the big and the small picture

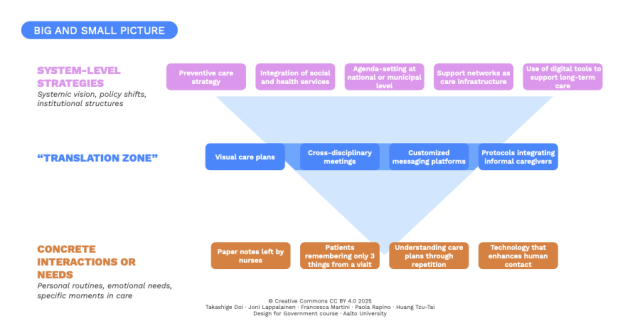

One of the most important learnings toward the end of this project was that zooming in and out between the system-wide vision and the individual realities of older adults is key. While our proposal promotes high-level strategic shifts, we also needed to address the everyday experiences that influence how people experience and engage with care.

For example, one key insight was that patients –especially older adults– tend to follow their care plans through repetition and simplicity. Currently, this is mainly done by nurses (or other health professionals) through a variety of channels and formats like messages, phone calls, or even handwritten notes. In contrast, digital health systems like Kanta present dense, medicalized information that is hard to understand—especially for patients who may be stressed or overwhelmed. As one doctor told us during fieldwork: “Patients usually remember only three things that have been agreed upon… they’re not necessarily nervous, but as these things relate to their health, they might forget” (Doctor 1, interviews).

That’s why our proposal—and future policy steps—must balance strategic shifts with tangible, human-centered improvements, such as making information clear, visual, and repeatable. “Technology must improve interaction with patients, not substitute it” (Administrative staff 1, interviews).

Figure 3. (Big/small picture): Systemic change requires addressing both structural policy and daily realities. This diagram illustrates how high-level strategies can be translated into human-centered actions.

Designing with humanity

This project made me realize how powerful qualitative research and design can be in shaping public systems. By crafting a compelling narrative—grounded in research and the lived experiences of those involved—we made our vision for preventive, community-based care easier to understand and act on. We also learned that making systemic shifts requires both strategic storytelling and attention to the small, human details that shape everyday care. As we prepare for our final presentation session, I hope our proposal sparks meaningful discussion—not only among our partners at the Ministry and KELA, but also among a broader public audience. Most of all, I hope it helps lay the groundwork for concrete action.

In both care and policymaking, we should remember what one nurse told us during fieldwork: “The most important thing is to meet people humanely” (Nurse 5, interviews). That, more than anything, should guide the future of health and design in government.

References

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., & Layton, J. B. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

Manzini, E. (2015). Design, when everybody designs: An introduction to design for social innovation. MIT Press.

The DfG course runs for 14 weeks each spring – the 2025 course has now started and runs from 24th Feb to 27th May. It’s an advanced studio course in which students work in multidisciplinary teams to address project briefs commissioned by governmental ministries in Finland. The course proceeds through the spring as a series of teaching modules in which various research and design methods are applied to address the project briefs. Blog posts are written by student groups, in which they share news, experiences and insights from within the course activities and their project development. More information here about the DfG 2025 project briefs.