This blog post reports on work-in-progress within the DfG course! The post is written by group 1A dealing with the Prime Minister’s Office’s brief on ‘Fostering Policy Coherence in Biodiversity’. The group includes Meeri Aaria from the Collaborative and Industrial Design program, Arpa Aishwarya from the Urban Studies and Planning program, Kamilla Grämer from the Creative Sustainability program, and Haoyue Lei from the Environmental Design and Creative Sustainability program.

Written by: Kamilla Grämer

Biodiversity loss is a wicked problem that affects not only the wellbeing of our environment but also the wellbeing of our species (Rittel & Webber, 1973). It is a common practice to separate the natural world from our human world when, in fact, the two are the same. When we speak of a human perspective on biodiversity, it should be no different than that of any other species on our planet. Yet our hierarchical systems as humans surpass those of our fellow Earthlings. Our parliaments and 4-year political cycles would put even the most advanced silverback gorilla society to shame. Nevertheless, when it comes to achieving the seemingly simple goal of maintaining our planet, a goal of which we are both technically and intellectually capable, humanity falls short. Are our social structures getting in the way of our natural obligations?

In support of our partners at the Prime Minister’s Office advocating for Biodiversity through policy coherence, our team set out to discover the points of leverage for improvement. The Finnish government’s stance on Biodiversity preservation has been fluctuating for as long as we could find due to the cyclical nature of politics, which leads us to question how the long-term goals to address this wicked problem are handled within the context of the policy cycle.

Although our project is only at its halfway mark, we have learned a lot about the processes behind policy coherence. I will attempt to summarise our research into two short paragraphs of key findings, starting with collaboration and motivation and moving on to the timescale of policy coherence in biodiversity.

Collaboration & Motivation

What we found was that policy coherence, like any old group work, comes down to collaboration and communication. The implementation of long-term strategies happens through siloed ministries with a limited to no overview of the long-term goal, leading to a fragmented solution to a complex problem. The topic of biodiversity is no different. Policies follow a larger long-term strategy, which goes through iterative cycles of compromises before they get published. Somewhere along these endless cycles, the main goal of the strategy is lost, and ministries end up publishing surface-level policy solutions to biodiversity, if any at all.

The policy cycle and a more realistic visualisation of the complex policy cycle © CREATIVE COMMONS CC BY 4.0 2024. Meeri Aaria, Arpa Aishawarya, Kamilla Grämer, Haoyue Lei. DESIGN FOR GOVERNMENT. AALTO UNIVERSITY.

With recent political shifts, contributions to Biodiversity preservation efforts happen on a strictly voluntary basis for Finland’s ministries. This means that individual motivation from ministries and their civil servants is now more important than ever. However, with the lack of information and overview of the problem even the best of intentions might fall short. That is, if the rare motivated civil servant dares to venture out into the unknown.

Timescale

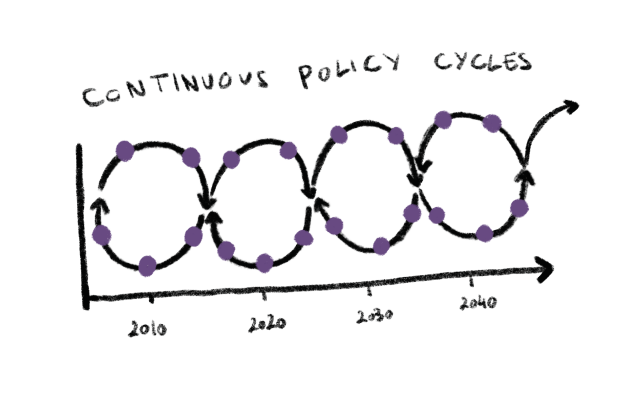

When we zoom out into a wider perspective of the policy cycle, we notice that the seemingly simple textbook graph hides further complexities. Policy cycles are not singular entities which can be addressed separately, but complex interconnected networks, happening simultaneously for the most part. There are multiple stakeholders participating in different parts of the cycle, with different levels of overview of the issues at hand. Political cycles also affect policy-making since the shifts in political attitudes can halt the process of biodiversity policies. Every 4 years, strategies are reviewed and adapted, with an endless cycle of compromises to fit the current political agenda. How could ministries and their civil servants foster any meaningful long-term agendas within this ever-changing complex system?

The cyclical policy cycle that continues over the years and is affected by the 4-year political cycles © CREATIVE COMMONS CC BY 4.0 2024. Meeri Aaria, Arpa Aishawarya, Kamilla Grämer, Haoyue Lei. DESIGN FOR GOVERNMENT. AALTO UNIVERSITY.

A policy cycle takes around 2-4 years before it is approved. In comparison, monitored species populations have declined by 69% since 1970, according to the Living Planet Index (2022)—all that in just 12 policy cycles. This leaves me questioning whether the existing political structures can withstand the pressing matters of our times. Can a system address the rapidly changing problemscape and provide effective and impactful solutions? Do the people of these systems wanting to contribute have the power and agency to make a change?

Systems are not designed for radical change, but the people working in them are often passionate about environmental causes. Perhaps the leverage point we need is the people. Maybe systems don’t care, but people do.

Conclusion

As we reach this halfway point in our project, we are left with more questions than answers. In comparison to the beginning, when our questions felt endless and open-ended, now we focus on phrasing the unknown as possible points of intervention. Instead of asking whether there is a collaboration between ministries to promote policy coherence, we ask, “How can we cultivate a place for collaboration and promote effective communication among ministries to meet the common goal of biodiversity protection?” “‘How can we break down the walls of ministry silos to work towards a shared goal?”

Personally, I wonder if our political systems can withstand the fast-paced challenges our world is facing. Does this framework require a shift in the way governments run? Can some goals surpass the 4-year political cycle?

Understanding the shortcomings of the policy cycle at our work session © CREATIVE COMMONS CC BY 4.0 2024. Meeri Aaria, Arpa Aishawarya, Kamilla Grämer, Haoyue Lei. DESIGN FOR GOVERNMENT. AALTO UNIVERSITY.

References and links for further reading:

- Ritchie, Spooner, & Roser. (2022). Biodiversity. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/biodiversity?insight=on-average-there-has-been-a-large-decline-across-tens-of-thousands-of-wildlife-populations-since-1970#key-insights-on-biodiversity

- Sitra. (2018, September 10). Phenomenon-based public administration. https://www.sitra.fi/en/publications/phenomenonbased-public-administration/

- Rittel, & Webber. (1973, July). Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. UrbanPolicy.net – Planning, Politics, Development. https://urbanpolicy.net/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Rittel+Webber_1973_PolicySciences4-2.pdf

The DfG course runs for 14 weeks each spring – the 2024 course has now started and runs from 26 Feb to 29 May. It’s an advanced studio course in which students work in multidisciplinary teams to address project briefs commissioned by governmental ministries in Finland. The course proceeds through the spring as a series of teaching modules in which various research and design methods are applied to address the project briefs. Blog posts are written by student groups, in which they share news, experiences and insights from within the course activities and their project development. More information here about the DfG 2024 project briefs. Hold the date for the public finale on Wednesday 29 May!