This blog post reports on work-in-progress within the DfG course! The post is written by group 1B dealing with the Prime Minister’s and the Ministry of Environment’s brief on ‘Biodiversity policy coherence’. The group includes Jing Lou, Jamie Smyth and Elli Törnqvist from the Creative Sustainability program and Annu Mathew from the Collaborative & Industrial Design program.

Written by: Annu Mathew

Transitioning from Detective Work to Design

For seven weeks now, we have been trying to understand the term biodiversity and what that means to the Finnish Ministry of Environment and the Prime Minister’s office’s role in leading this project. We interviewed many civil servants and experts from the field, followed the media and read many research articles on biodiversity policy. We analyzed all that information into rich insight statements¹ containing pieces of evidence we gathered from our research. We also drew a systems map² with the ministry’s various actors and how policy flows between them. All of these were presented to our project partners. We also highlighted the opportunity areas where we could possibly intervene to help change the system and guess what? Our partners loved it!

Image 2. The insight statements and the evidence presented during the mid-term presentation.

Okay so now to switch roles from research to design(cracks knuckles). Ready? Let’s design for policy!

Only there’s a problem: None of us has done this before. My diverse team members have backgrounds in graphic design, industrial design, and business, but design for policy was a new experience for us. This course is a first-hand practical journey for us in learning how to design for the government.

“We apply human-centred approaches to identify stakeholder needs, systems thinking to analyse the wider context of policies, and behavioural insight to identify and design relevant solutions to policy change.” – DfG course structure and design approach.

Exploring intervention opportunities

As we embarked on this learning, we were reminded that design for policy does not need to be a tangible, transforming, or even a feasible solution. In her article Leverage points: places to intervene in a system and how much of an effect the intervention has, Donella Meadows gave us a starting point for this: a compilation of 12 points of intervening in a system and assessing the impact of those interventions.

Ahh, perfect!! This gave our team a starting point; we could now start boiling ideas with a focus on systemic change. These changes could be small shifts to significant changes we want to achieve. In addition to identifying intervention points, we crafted vision statements to help set limits and comprehend what we aim to achieve collectively. These statements, made collaboratively with fellow students addressing the Biodiversity topic fostered a shared understanding and provided a compass for our design interventions. Although each group approached the challenge of biodiversity policy coherence from a different angle, our overarching ambition remained unchanged. We want to change the world, and we have to start small, and for that, the boundaries have been drawn. The ideas we call ‘entry points’ are not concrete yet; instead, they are an efficient place within a system where work to improve it might begin.

Image 3. One of the vision statements made by the supergroup.

The role of a designer

As we persist in pinpointing our entry points, we consistently reflect on our roles as designers. How can we leverage our varied strengths and experiences from diverse cultural backgrounds to effectively apply them in this fresh context? Jocelyn Bailey(2016) delves into participatory, co-design and service design methodologies to enhance service delivery and shape strategy and policy. The adoption of these design approaches may draw critique from various political perspectives. It’s important to note the distinction between design and policy; while policy is entrenched in bureaucratic processes and subject to political cycles, legislation and laws. Design operates around problem-solving through creativity, empathy and iterative processes.

As designers and external consultants in this project, we have strengths and weaknesses. We could point out what’s not working in the system, but at the same time, we may not have enough authority and power to change the system fundamentally. For example, one leverage point we would be interested in introducing at the Ministry of Environment would be #4: the power to add, change, evolve or self-organize system structure. This leverage point, which seems to have a significant effect in terms of change and highlights the resilience of a system, would be an ideal one to implement. As designers, one of our abilities is to identify what’s possible and what’s not and, at the same time, find creative means to work around that leverage point.

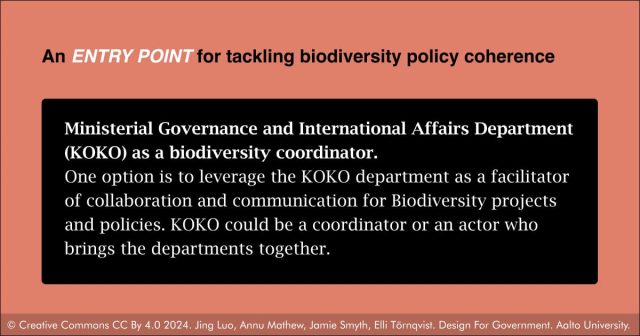

An example of how we worked around this is identifying one department that could be leveraged to mainstream biodiversity and build capacity rather than reorganizing the entire structure of the Ministry of Environment. See below how we framed one of our entry points.

Image 4. An entry point identified by group 1B.

Design, a practice perspective

Another strength of design is that it takes a practice perspective. Policy design and practice could mean co-creation and co-production. We are now in the midst of translating these entry points into visuals. These visuals show how we achieve the vision we are aiming for. We then present this to our partners during an ideation session, where we engage in a dialogue, co-producing the entry point further. This collaboration of viewing it with different lenses would result in a more effective proposal that both the civil servants and we designers would find compelling. Yet again, it will be a learning moment for us to see how design is being mobilized to extend and enable governance techniques.

My team and I are thrilled about this phase of the project, as it allows us to leverage our design expertise beyond our own expectations! We eagerly anticipate the next stages. Keep an eye out for our final proposal.

References

-

Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System. (1999). The Academy for Systems Change. Retrieved April 16, 2024, from https://donellameadows.org/archives/leverage-points-places-to-intervene-in-a-system/

-

University of Brighton, Bailey, J., & Lloyd, P. (2016, June 25). The introduction of design to policymaking: Policy Lab and the UK government. Design Research Society Conference 2016. https://doi.org/10.21606/drs.2016.314

Definitions

-

Insight statements: articulate the most valuable learning or “aha” moments that emerge from research. They inspire others to take action (Ideo designkit).

-

Systems map: A commonly used tool to make sense of complex systems. It lays out all the relationships and interactions between stakeholders in a given system (IdeoU).

The DfG course runs for 14 weeks each spring – the 2024 course has now started and runs from 26 Feb to 29 May. It’s an advanced studio course in which students work in multidisciplinary teams to address project briefs commissioned by governmental ministries in Finland. The course proceeds through the spring as a series of teaching modules in which various research and design methods are applied to address the project briefs. Blog posts are written by student groups, in which they share news, experiences and insights from within the course activities and their project development. More information here about the DfG 2024 project briefs. Hold the date for the public finale on Wednesday 29 May!