This blog post reports on work-in-progress within the DfG course! The post is written by group 2B dealing with the Ministry of Transport and Communications’ brief on Accessible Traffic Chains. The group includes Carlotta Carvalho from Collaborative and Industrial Design program, Giorgia Morandi from the Creative Sustainability program, Pai-Feng Chen from Collaborative and Industrial Design program, and Ruth Kupiainen from International Design Business Management program.

Written by: Ruth Kupiainen

In this post I will be talking about systems, just like our own nervous system. You must be wondering how this relates to the accessible transportation chains… Let’s go back to the beginning to our reframed research question: How does the information find the user?

Since the mid-term presentation, this has been the only question in our minds. At last, realistically, feasibly, and successfully, we can now say, we’ve got the answer!

Accessible information = accessible travel chains.

What information?

“Real-time, up-to-date, accurate information found on the internet is essential, otherwise trips may not be made. People get discouraged and don’t go.”

– Accessible travel expert and blogger, 2023

To ensure the inclusion of users who face mobility challenges, such as, but not limited to individuals with physical impairments, the elderly, and those with buggies, it is crucial to establish accessibility standards. Setting a threshold for the standards is especially important, so that these users who are more vulnerable in terms of mobility can fully participate in the life of society. Implementing universal design principles, such as promoting simple and intuitive usage and providing easily understandable information, can greatly contribute to addressing these accessibility needs. (Dadashzadeh, Sucu Sagmanli, and Ouelhadj, 2022).

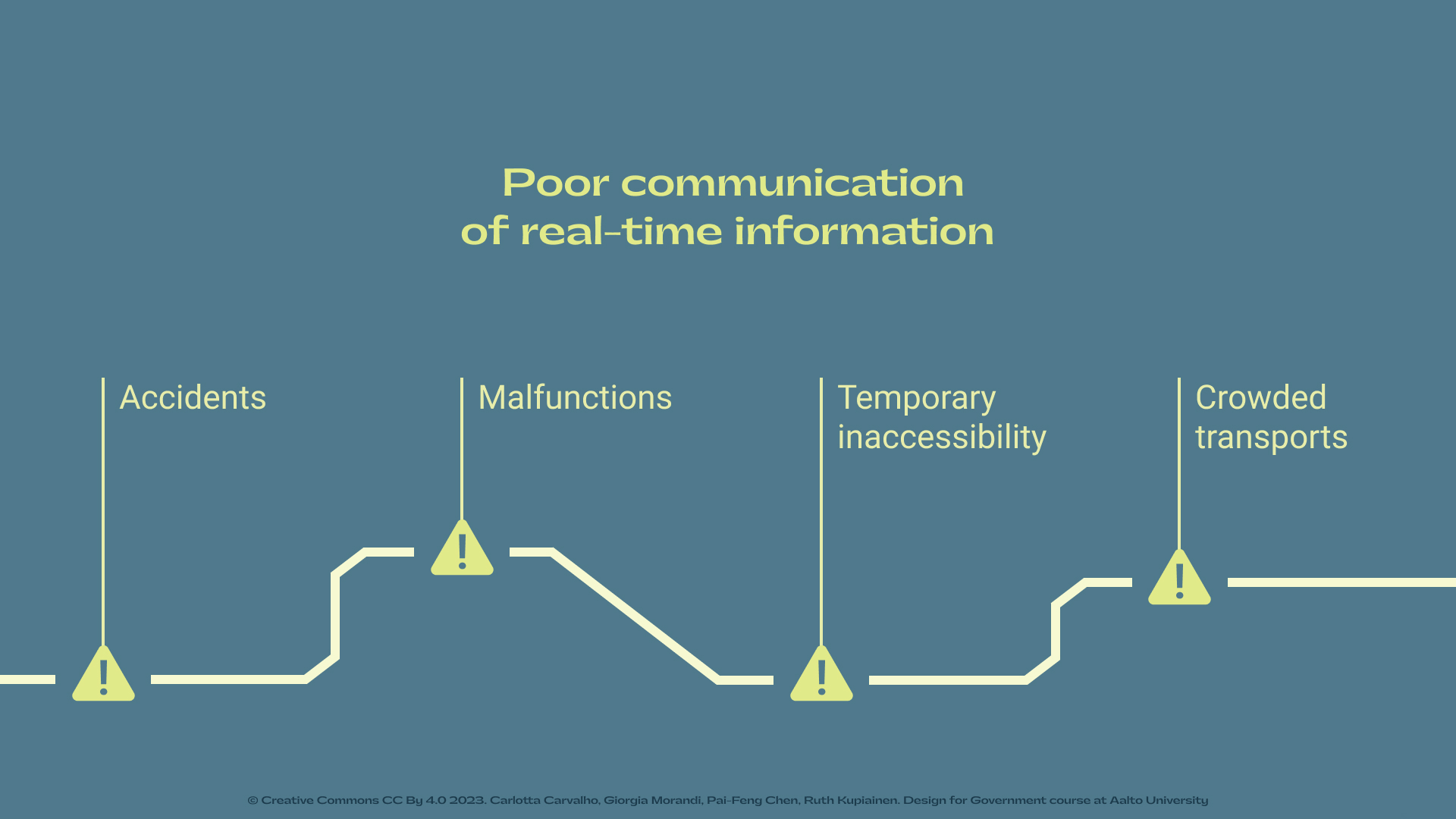

From the user interviews with representatives of different vulnerable groups, we identified that the crucial phase of accessible travel is planning before the travel even begins. Planning requires time, and real-time accurate information is one of the most important factors in planning. We confirmed that the relevant travel information, such as accidents, malfunctions, temporary inaccessibility of stops, or means with full capacity, is not collected and made available for users in real-time. This undermines the reliability of means of transport and makes it difficult to plan journeys in advance.

So, whether one has a physical limitation, luggage, pushchair or simply has to get from point A to point B, one must be able to plan the journey according to their needs and be sure to reach the destination safely. The information that supports this type of travel, is what we refer to.

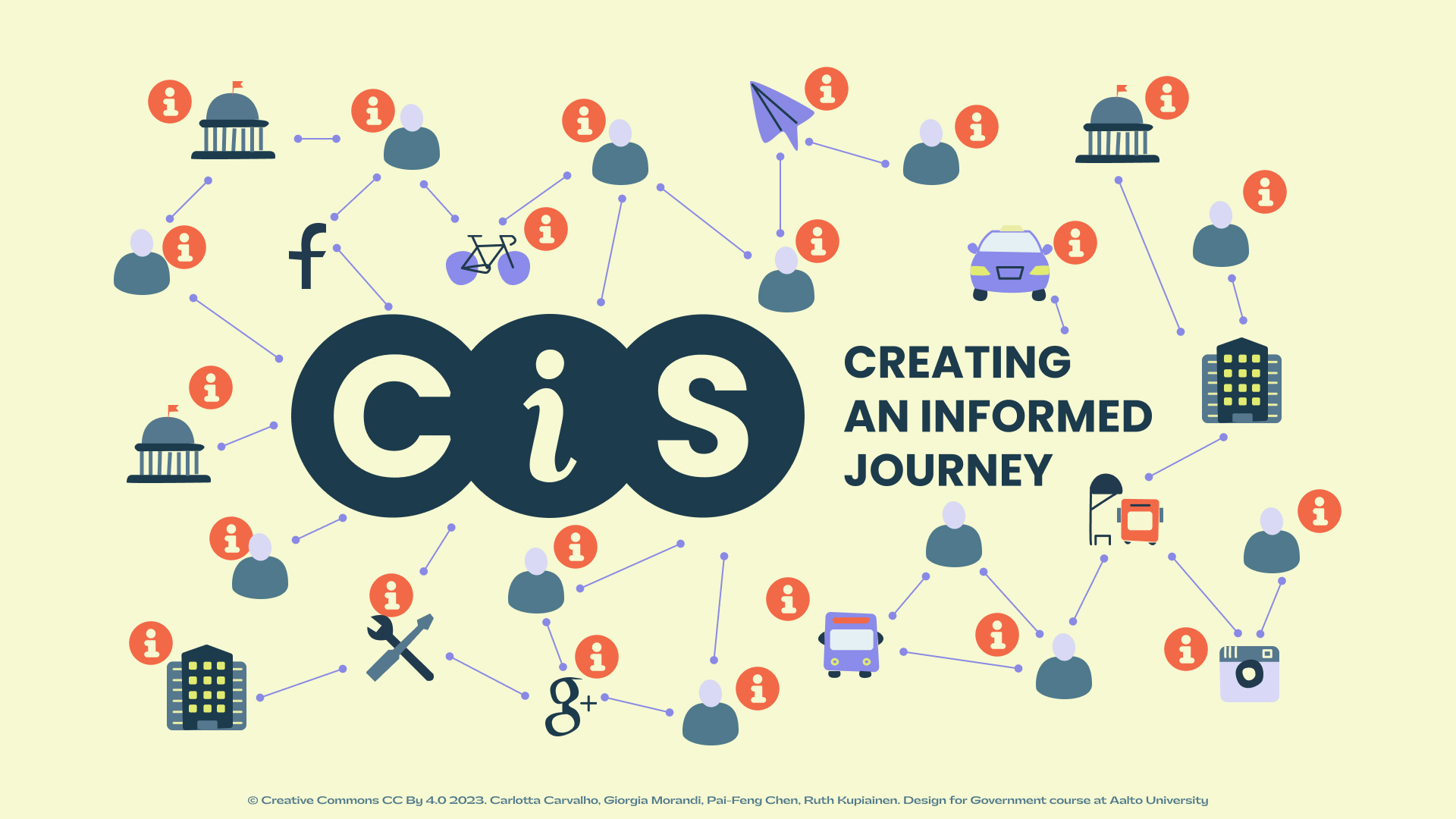

Currently, different sources of information are spread across multiple platforms and stakeholders. When someone notices a problem, others can’t reach that information. To bridge those gaps and make accessible information real-time and available to every user, we need to connect all the actors together and put them on the same page.

To start the small changes in this complex information system, and to eventually produce bigger changes in the broader transport system, we chose to focus on three points according to Meadows’ leverage points (1999):

- Firstly, evolving the structure of the information system, by promoting collaboration between stakeholders and transforming the users’ role from passive to active.

- Secondly, defining the rules of the information system, by creating new regulations and setting a standard for sharing information.

- Lastly, structuring the information flows through co-creation sessions, bringing together stakeholders and citizens.

These leverage points helped us to identify where we should place our proposal and the type of interventions to design. Looking back, they were the pivoting moment for our project, as we understood that to approach and affect the complex system, we only need to focus on a few specific minor locations within it. Other impact across the entire system will come as a ripple effect of those interventions.

How to achieve the changes in the system?

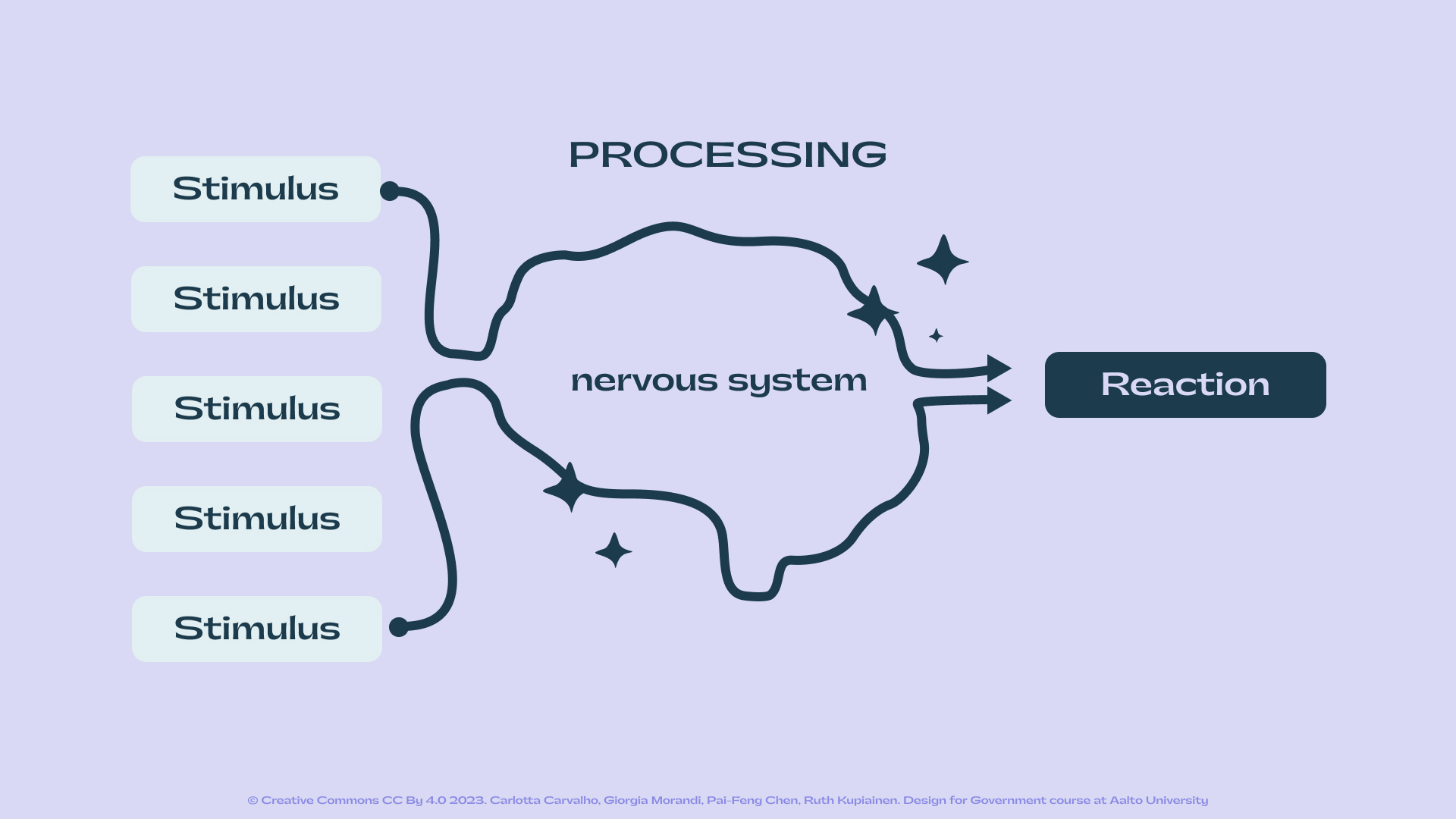

Let’s return to the analogy of the nervous system. The human body operates as a system with a central point, our brain, through which every signal passes (Figure2).

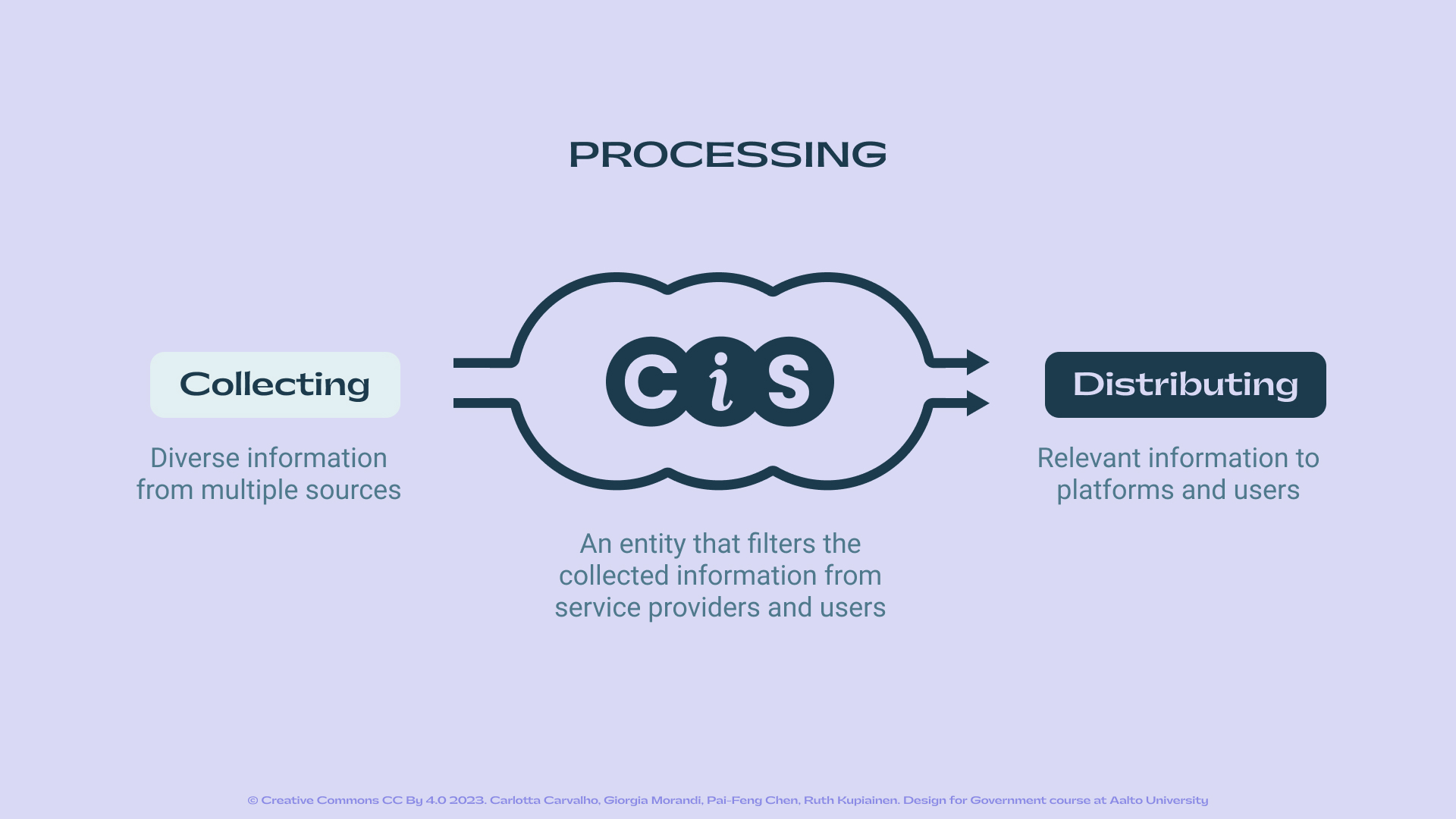

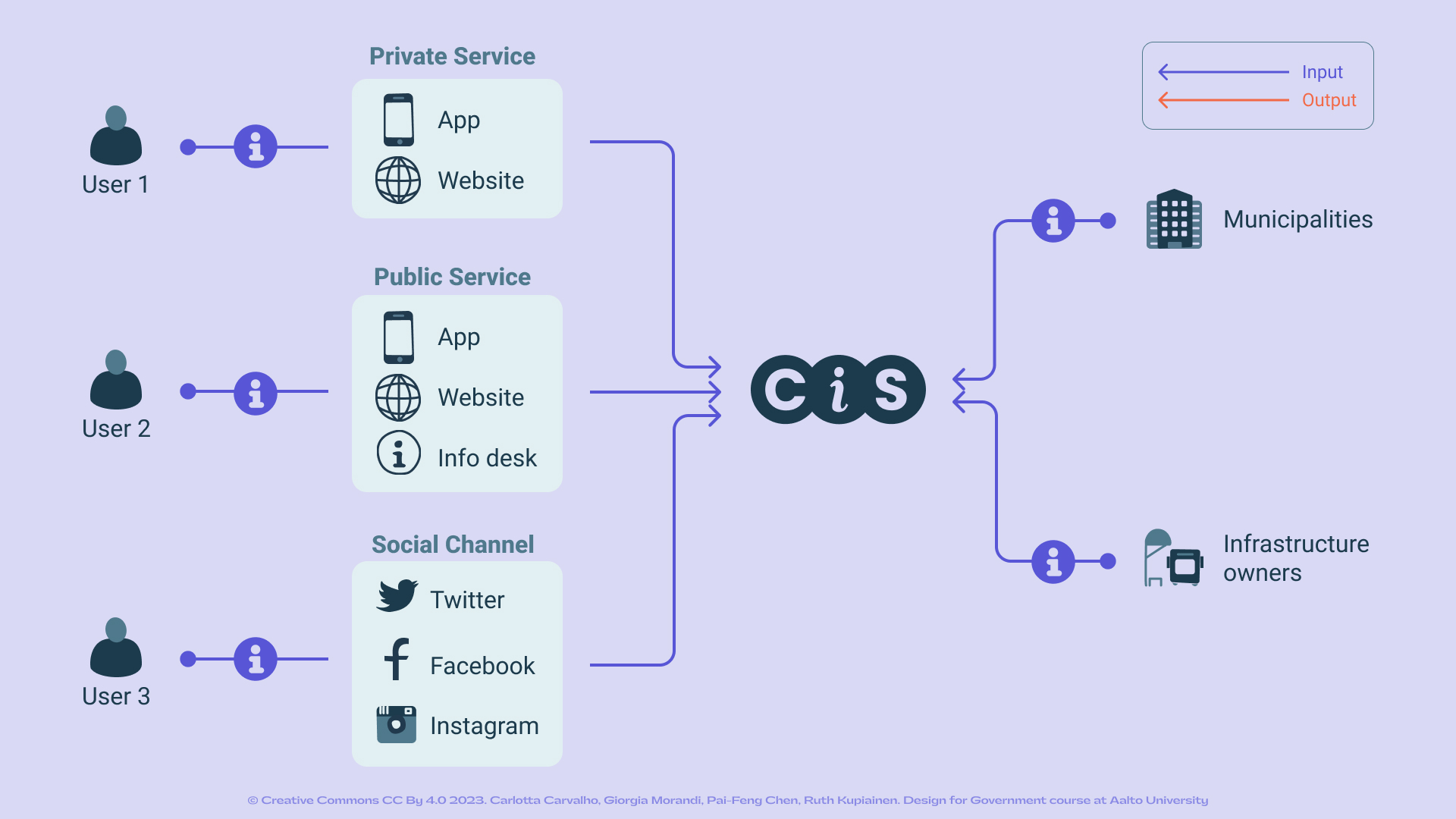

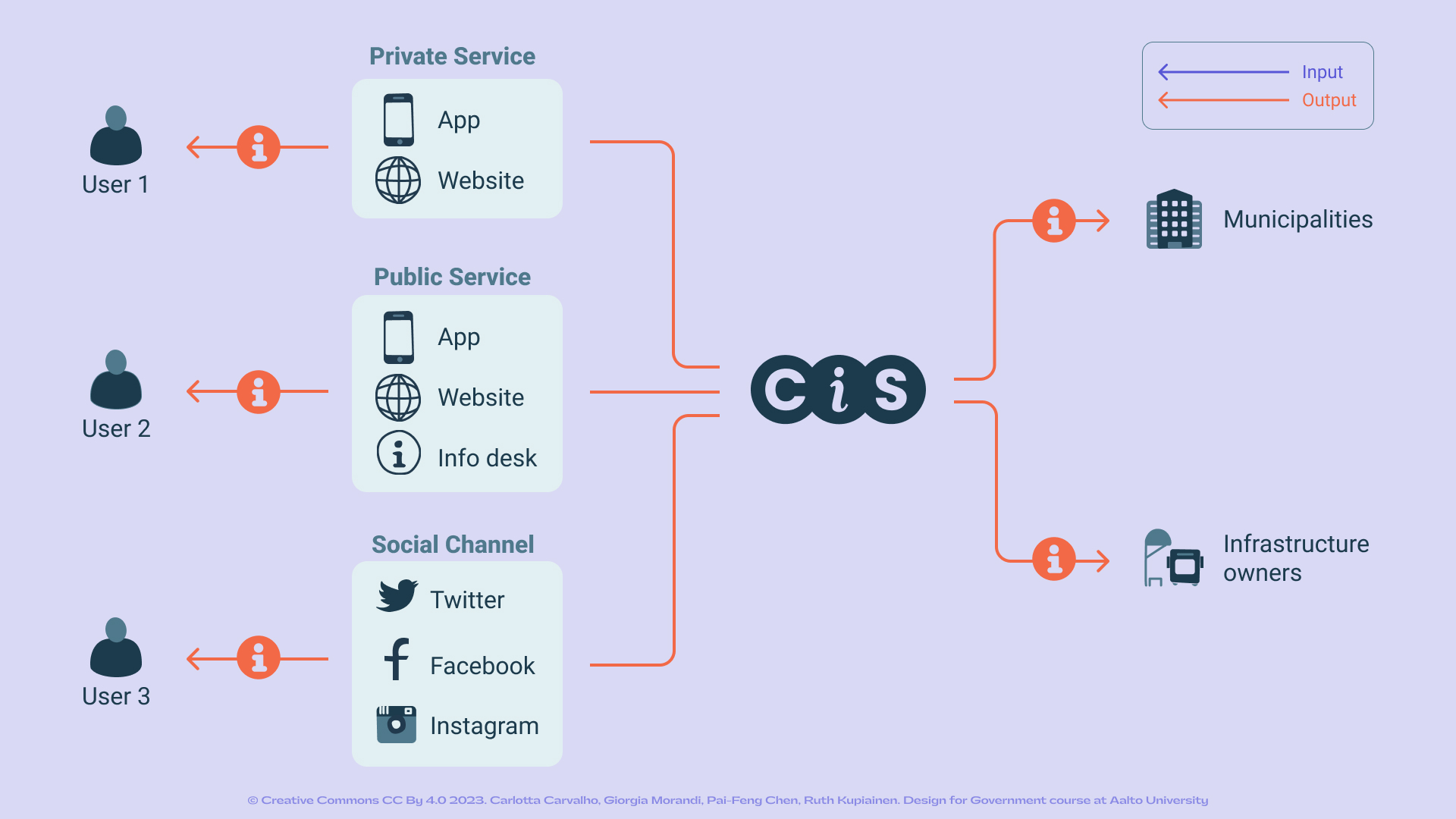

Now, imagine a platform with a central database for collecting, processing, and communicating real-time and accurate information to the users. What we propose is a very similar system: CIS – Centralised Information System. However, instead of stimulus, the system collects diverse sets of information from multiple sources and filters them to be sent to the user through different service platforms (Figure 3). This information includes all the input regarding unforeseen events that can occur inside the transport, stations and all the infrastructure that interfere with a travel journey.

According to our user interviewees, sometimes the information regarding an impediment on a route can be faster found from another user’s feedback post, rather than service providers. Therefore, in addition to the contribution of public and private service providers, agencies, and municipalities to the input of real-time information, we decided to include the users’ contribution, too.

Users can provide updates on events that happen on the spot, through different feedback channels, such as the ones from service providers, private companies, and social media. The system filters, verifies and analyses both feedback and information input through an AI-based platform, trained by a specialist team. The processed information is sent to service providers in real-time which supplies the users with accessible travel planning. The information flow is reciprocal, and all information is open source, which means all actors involved in the system have access to it. This is important, for example, for making the system more transparent, reliable, and easily usable.

Where to start?

How do we get everyone on the same page to get started? Our solution is made of two steps. Addressing the accessibility of travel chains from the local level, we use the Greater Helsinki area as an example. We propose the following action plan:

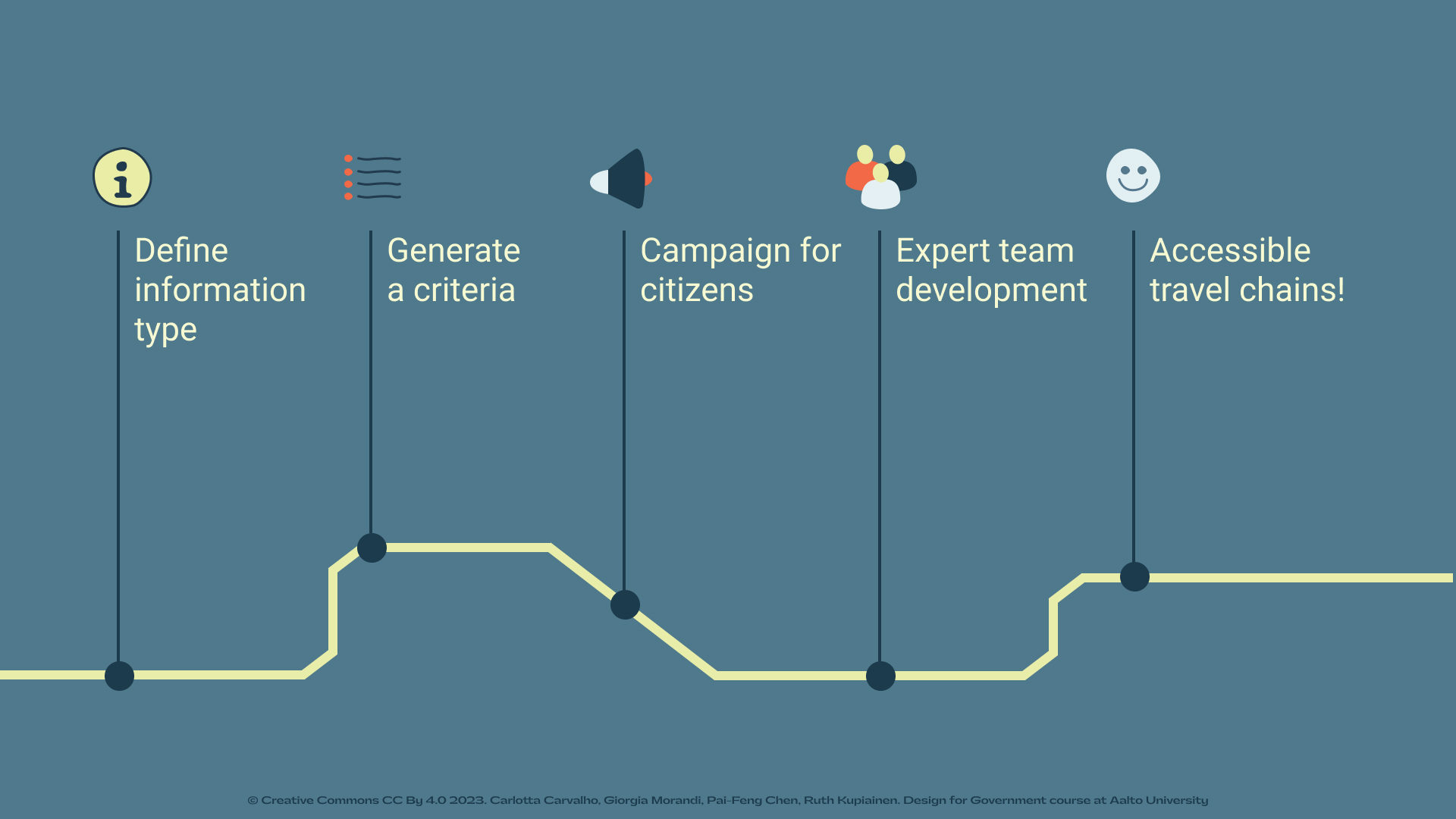

- Step 1 is a set of co-creation workshops for stakeholders and citizens to understand together what information needs to be collected to build a smooth and accessible travel chain.

- Step 2 is to generate criteria based on the workshop decisions. To make sure that Step 1 stays reliable, we then need to set a new regulation for each actor of the system to follow.

- Next phase is to organise a campaign to give citizens the incentive and understanding of why their contribution is important for the system.

- For the future vision of the system, a team of experts will continuously develop the platform.

- This way we can reach the goal of providing accessible travel chains for every citizen.

These steps were chosen based on our understanding of the stakeholders’ needs from both sides. Step 1 is a prioritised list of actions in selected accessibility journeys. Step 2 is to standardise accessible travel chains. In addition, with the possibility to report travel disruptions, users can get a sense of ownership in the system and feel more empowered. Whereas, by regulating every stakeholder to provide the agreed information into the centralised system, the service providers and maintainers can enjoy the shared responsibility. (Read about the CIS system proposal and its benefits in more detail in our project report.)

So, how does the information find the user?

Understanding context is crucial for success, and there is no context without all the relevant parts. In our case of accessible travel chains, those relevant parts are both the ones who provide and manage the services and the ones who use them. By working with the groups that require the most accessibility we can achieve to define and provide accessible information for all. Based on the experiences of the vulnerable groups, we gathered that for the information to be accessible, it needs to be accurate (i.e., real-time and relevant) and centralised (i.e., easily found from one place). We can argue that these kinds of metrics are quite universal and apply to all other users in less vulnerable positions too. Studying how these user groups use the information to plan their journey and by involving them in the process of deciding what information is relevant and how it should be shared, the accessibility standard is set based on real needs.

Reflecting on the project, the greatest moment for me has been the realisation that our stakeholders understood the context the same way as we did. Yes, this information has found the partners! They understood the importance of co-designing and user’s role within the system. By working as an example of collaboration within our three groups we managed to show the value of it and convey how all our projects link together to create a system just like theirs. Most importantly, this project has taught us that design has the power to shape policies and create tangible solutions that affect the quality of life for all citizens.

Conclusions

In summary, our proposal is to create a framework for building an information system called CIS that shares real-time information using a collaborative approach. This system empowers users to take an active role in achieving this goal. Similar to our nervous system, the network of information and various actors is the very basis for the smooth functioning of travel chains. By networking the disconnected information, we look at a more informed and accessible travel future.

To question the proposal, we could start by thinking about privacy issues and the amount of accessibility group users for the system to work. Is it about the quantity or the quality (valuable input)? Is anonymising the feedback enough? Can feedback from public social channels be utilised? Some next steps for this proposal would also be to think how the success of such framework implementation could be measured – what the metrics would be. First things first though – getting all the stakeholders into one room to spark the co-creation. May our proposal not only be utilised, but taken into pieces, adapted, and patched back together as seen necessary!

On behalf of my team, I thank the interviewees from user groups, project partners and other involved stakeholders, as well as the teaching staff for believing in us, for questioning us and, finally, for listening to us at the final show. Looking forward to seeing how the National Transport System Plan 2021-2032, Transport 12, will implement the accessibility measures in the upcoming years.

Let’s make it happen CISters!

References:

Dadashzadeh, N., Sucu Sagmanli, S., & Ouelhadj, D. (2022). Inclusive Mobility as a Service (MaaS): key performance indicators and a conceptual framework for evaluation. In The Proceedings of the ICoMaaS2022 Conference Tampere University. https://events.tuni.fi/icomaas2022/pro/

Meadows, D. H. (1999). Leverage points: Places to intervene in a system.

The DfG course runs for 14 weeks each spring – the 2023 course has now started and runs from 27th February to 31st May. It’s an advanced studio course in which students work in multidisciplinary teams to address project briefs commissioned by governmental ministries in Finland. The course proceeds through the spring as a series of teaching modules in which various research and design methods are applied to address the project briefs. Blog posts are written by student groups, in which they share news, experiences, and insights from within the course activities and their project development. More information here about the DfG 2023 project briefs.

What is the focus and objective of the work-in-progress project reported in the blog post, and how does Group 2B collaborate with the Ministry of Transport and Communications in this context? Can you provide details about the members of the group and their respective programs, as well as the specific project they are working on related to ‘Accessible Traffic Chains’?

1. Copy/Paste your script or any add any website, blog or

article link.

2. With 1 click our A.I. turns it into an engaging video with slides, images, videos, music

& even voiceover.

3. Upload the video, get ranked on Page #1 and start getting real traffic & sales!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xzxgniI6GSkaalto.fi