This blog post reports on work-in-progress within the DfG course! The post is written by group 1 dealing with Kela, the Social Insurance Institution of Finland’s brief on ‘Continuity of Knowledge’ in healthcare reform. The group includes Takashige Doi from Collaborative and Industrial Design program (Aalto University), Joni Lappalainen from Collaborative and Industrial Design program (Aalto University), Francesca Martini from Creative Sustainability (Aalto University), Paola Rapino from Creative Sustainability (Aalto University, exchange) and Huang Tzu-Tai from Sustainable Entrepreneurship (Aalto)

Written by: Takashige Doi

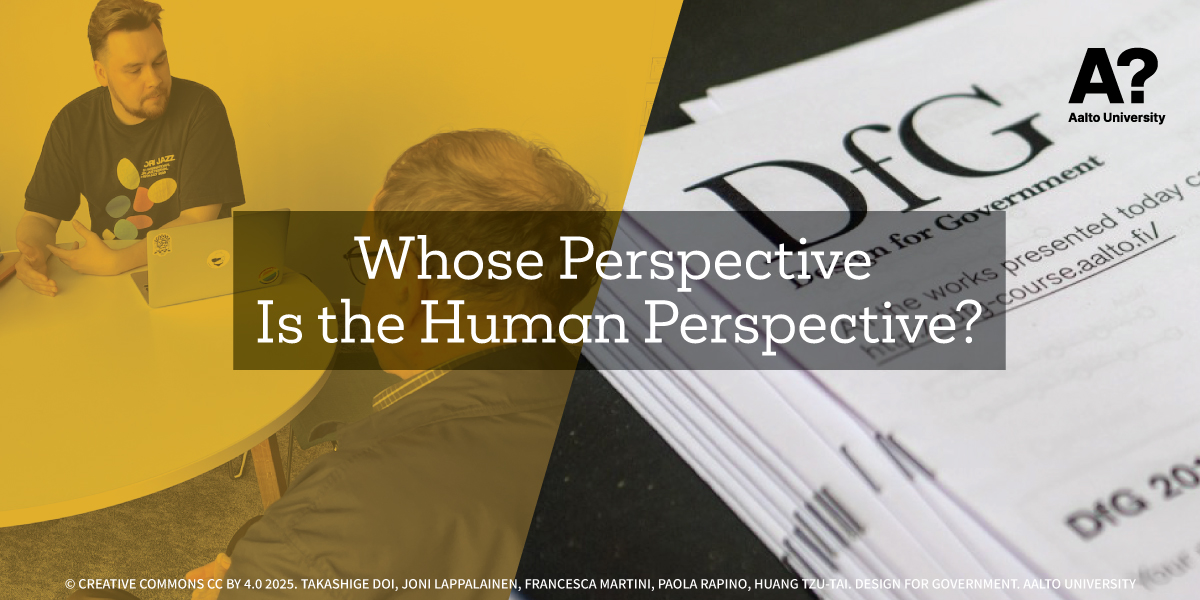

For the past seven weeks, our team has been exploring how knowledge is passed on and shared in Finland’s elderly care system. We’ve completed the context setting and system thinking phases in this course, and we’re now focusing on the human perspective. But when we talk about “the human” in elderly care, it’s not just about the elderly themselves. There are many different stakeholders involved, each bringing their own goals and perspectives. In this post, I’d like to share some reflections on the difficulty of drawing insights from the human perspective

Figure 1. We are here in the process.

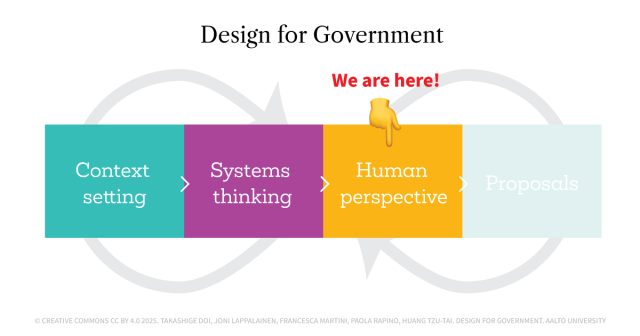

Abduction in Design Research

While preparing for our fieldwork, one of the most memorable approaches I learned in qualitative research & design was abductive reasoning. Abduction is a way of thinking that helps us create plausible and creative ideas based on incomplete or uncertain information. While deduction tests theories and induction builds general rules from examples, abduction is different—it allows us to rethink assumptions and approach complex problems from a new angle (Dreamson & Khine, 2022). This approach felt especially relevant for design research, where uncertainty and complexity are common. In fieldwork, data is not collected to prove a fixed idea, but to deepen and refine theoretical understanding as new insights emerge (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Inductive, deductive, and abductive research approaches, and the selected method. (Adapted and revised from Ketokivi & Choi, 2014; Costa, Soares, & Sousa, 2017)

In our midterm presentation, we proposed a hypothesis: social workers may play a key role in maintaining continuity of care through human interaction, which facilitates the transfer of tacit, experience-based knowledge. They are positioned between formal healthcare providers like doctors and nurses, and informal caregivers like family and friends. We believe that social workers might hold valuable insights and practical experience that aren’t recorded in systems like Kanta. These include knowledge gained through direct interaction with patients, an understanding of their daily routines, emotional states, and social contexts

This kind of knowledge, gained through direct interaction with patients and an understanding of their daily routines and social contexts, could help fill important gaps in care, especially within the human side of the patient experience that formal systems often miss out on. With this hypothesis in mind, we carried out our fieldwork using an abductive approach. Instead of being limited by existing policies in the Finnish healthcare system, we focused on discovering new meanings and patterns through interviews and visits. This helped us explore how existing care models could be reframed by listening to voices and insights that are often left out of formal records.

Different Perspectives, Fragmented Knowledge

Through our fieldwork, we noticed that many different actors are involved in elderly care, and their perspectives often do not connect smoothly. As a result, the flow of information and knowledge can become fragmented. By April, we had completed one visit and 14 interviews in total (eight care professionals, three senior patients, and three administrative personnel). Our team divided the transcripts and worked together to analyze the content, organizing key observations into several themes.

We found some challenges in human interaction within elderly care. While systems like Kanta include key details such as care plans and treatment instructions, this information isn’t always used effectively. Nurses often need to repeat instructions by phone or text. When elderly people lack support from family or neighbors, it becomes harder to help them early in the care process.

Based on what we saw, it seems that even though the Sote reform in Finland is working towards to improve equality and efficiency in health and social services (Tynkkynen et al., 2023), there are still gaps between the policy goals and what actually happens on the ground. In particular, during our research, we began to notice signs of what Meadows (2008) calls ‘policy resistance’—a situation where different actors have different goals and end up working against each other. In elderly care, this means that while government, healthcare, and social services each try to optimize their own tasks, it becomes difficult to provide integrated care that truly works for the people using the system.

Figure 3. Through interviews and analysis, we discovered a variety of perspectives in elderly care—and found that knowledge is often fragmented.

Seeing the Elderly as Human Beings, Not Just Patients

Through our initial fieldwork, we developed an insight based on several interviews: The patient’s care circle plays a crucial role in transferring practical knowledge to them and ensuring they follow their care plans. However, after receiving feedback, we decided to revise it to make the wording feel less abstract.We were also advised to include multiple sources from different perspectives to support our insight more clearly.

In further discussions, we realized that our fieldwork lacked the perspective of social workers. Around the same time, we had the chance to interview a senior lecturer who teaches elderly care at a Finnish university. One comment from that conversation stood out: “While nurses often focus narrowly on physical symptoms and treatments, social workers take a broader, more holistic view—trying to understand the whole human”. This made us rethink the importance of seeing the elderly not just as patients, but as human beings.

Personally, I realized that I had unknowingly fallen into the kind of bias we learned about in a lecture during the course -specifically, the type related to “understanding mapping”, where people struggle to grasp complex relationships, as described in the framework of choice architecture (Thaler, Sunstein, and Balz, 2012). As they explain, humans are not perfectly rational—they are prone to bias, error, and distraction.

Moving forward, we would like to update and clarify our insight based on what we’ve learned. We also plan to continue interviews and observations to test our ideas and develop a proposal that people across the elderly care system can understand deeply and support with empathy.

References

Costa, E., Soares, A. L., & de Sousa, J. P. (2017). Institutional networks for supporting the internationalisation of SMEs: The case of industrial business associations. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 32(8), 1182–1193. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-03-2017-0067

Dreamson, N., & Khine, P. H. H. (2022). Abductive reasoning: A design thinking experiment. International Journal of Art & Design Education, 41(3), 403–413. https://doi.org/10.1111/jade.12424

Meadows, D. H. (2008). Thinking in systems: A primer. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Thaler, R. H., Sunstein, C. R., & Balz, J. P. (2012). Choice architecture. In E. Shafir (Ed.), The behavioral foundations of public policy (pp. 428–439). Princeton University Press.

Tynkkynen, L.-K., Keskimäki, I., Karanikolos, M., & Litvinova, Y. (2023). Finland: Health system summary 2023. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Retrieved from https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/i/finland-health-system-summary-2023

The DfG course runs for 14 weeks each spring – the 2025 course has now started and runs from 24th Feb to 27th May. It’s an advanced studio course in which students work in multidisciplinary teams to address project briefs commissioned by governmental ministries in Finland. The course proceeds through the spring as a series of teaching modules in which various research and design methods are applied to address the project briefs. Blog posts are written by student groups, in which they share news, experiences and insights from within the course activities and their project development. More information here about the DfG 2025 project briefs. Hold the date for the public finale on Tuesday 27th May!