Editor’s note: We offered this blog as a platform to the DfG course participants who are documenting the DfG course for readers to get a glimpse of how things went. This is one such post by School Fruits and Vegetables team 1.

What are we up to?

We are working with the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry to look into the EU-wide School Fruit and Vegetable Scheme (SFVS) and how it could be implemented in Finland. SFVS aims to provide school children with fruit and vegetables for sustained, healthy eating habits. The diet of children in EU is shifting towards highly processed products, and overweight and obesity are increasing. WHO estimated that every third child between 6 and 9 years old are overweight or obese in 2010, compared to every fourth in 2008. The Ministry wishes to utilise the EU scheme for healthier eating habits through education.

The scheme is implemented in many other countries but not in Finland. One of our main tasks is to understand, why the scheme has not been implemented before. We believe that by looking into what is the status quo, we will find some answers on how to implement the scheme in the future.

During the first six weeks of DfG 2015, we’ve been carrying out a 20 interviews with stakeholders and a number of observations in different schools, planning co-creation workshops, preparing and sending out design probes, and looking for and reading relevant EU-legislation and recent research findings.

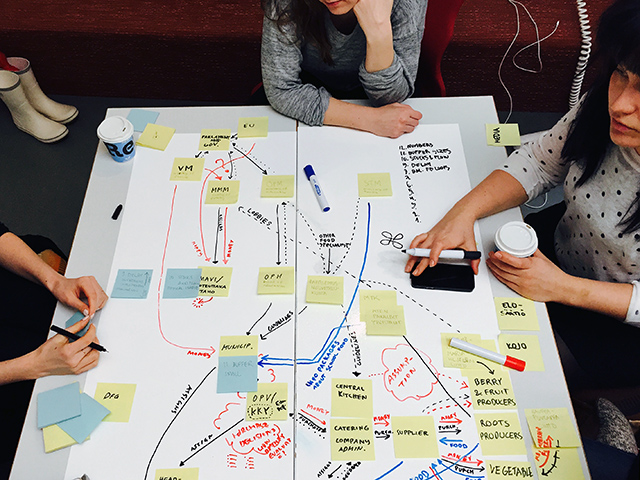

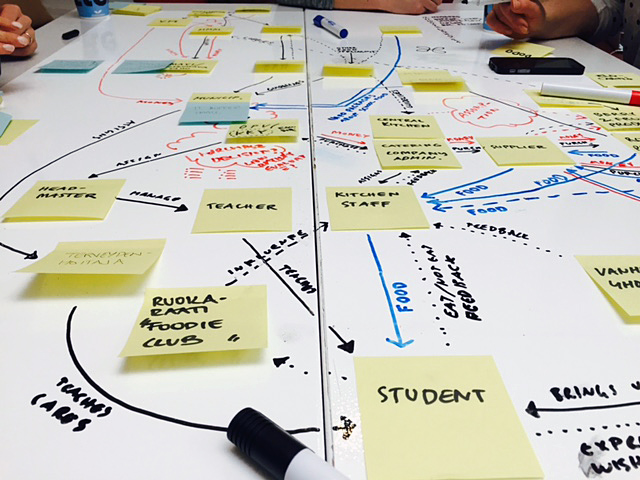

Our project is defined by a wide range of stakeholders from different levels, from municipal decision makers to kitchen staff, kids, parents and producers. This is where the systems approach and mapping becomes very useful. During the two week time, we discussed about different streams of systems thinking, cases and implications on our projects.

What is Systems Thinking?

A system is a set of things – people, cells, molecules, or whatever – interconnected in such a way that they produce their own pattern of behavior over time (Meadows, 2008). For instance a body is a system and its parts would be cells, muscles, digestion, lungs, blood and so on. An organisation is a system and its parts would be people, structures and processes. Together these parts form a pattern of behaviour which is driven by the systems goal. The goal of the body for instance is simple – to stay alive. All the behaviour formed by it’s parts support this goal.

Systems Thinking has been used in different disciplines since the 30’s, for instance in ecology, game theory and management. Systems Thinking is the process of understanding how things, regarded as systems, influence one another within a whole.

It is a useful way of understanding how complex systems, such as governments, work and what kind of problem cycles and leverage points can be seen. If you want to understand Systems Thinking quickly, this Ted Talk might be a good, short introduction: www.drawtoast.com

And, then it gets confusing…

Systems thinking is a true brain exercise, when you first get into its essentials such as feedback loops, delays and barriers. Luckily some of us we were familiar with Systems Thinking theories before hand.

Systems feel a bit confusing because in real life systems have no boundaries. Everything is connected to everything. So another important thing to understand about system maps is that they are only representations and in that sense are not real. We all also understand systems differently. When drawing systems models or decision making it is important to make clear and careful choices on boundaries. If the boundaries are too tight, the key of the system can be missed. If it is too wide, it is impossible to make any conclusions.

Another notion is that world is not linear and delay is everywhere. This is one reason why systems so often surprise us despite our careful planning. You might even reinforce a vicious circle by linear action though your attention is the opposite. “If we’ve learned that a small push produces a small response, we think that twice as big a push will produce twice as big a response. But in a nonlinear system, twice the push could produce one-sixth the response, or the response squared, or no response at all” says Meadows.

We started our system exploration with Thinking in Systems book, which is a great introduction to systems, but will get back to you over and over again as your system understanding increases. If you are a policy-maker and only have time for one chapter, read Chapter 5 System Traps and Opportunities, you will make time to read the rest.

To get different viewpoints on systems thinking, we had guest lectures from Samuli Kortelainen of SimAnalytics, Hella Hernberg of Urban Dream Management in person and Skyped-in Jonathan Veale, the director of Strategic Foresight Unit at the Ministry of Health at Government of Alberta, Canada. Veale’s lecture gave us very concrete examples on how horizontal the work of a designer has to be in order to achieve change in the government.

Hella Hernberg introduced us to the project Vacant Spaces she did while working as an embedded designer in the Ministry of the Environment. The focus of the project was to explore how unused buildings and spaces could be repurposed and taken back into use without major renovation. The main learning for our project was that embracing existing structures and seeing them in a new light can allow us to do big things with small resources. Redesign with minimal changes can be just as effective as a new design, but requires only a fraction of the resources to implement. The existing administrative structures set many boundaries on how the SFVS could be implemented. On the other hand they are the very thing that make implementing the scheme possible in a realistic time frame and budget, which is why we should follow Hella’s example and see them as opportunities rather than restrictions.

The main learnings for our project from Samuli Kortelainen’s lecture were the importance of setting boundaries for our system, and trying to find the parameter in the system for the change of which the system is the most sensitive. Kortelainen introduced us a very mathematical way of approaching systems, which uses data based computer simulations to predict the likelihood of different outcomes in the system. This so-called hard approach, that Kortelainen is practicing, differs from the designerly way of using systems thinking. It was interesting to notice a lot of similarities in the ways of making sense about a system, even though the methods are quite different. Kortelainen talked about how which parameters are important depends on how sensitive the system is for a change in each parameter. That brings us directly back to Meadows’ leverage points.

While Kortelainen had a hardish approach a book Learning For Action written by by Peter Checkland and John Poulter opens a softer approach – it’s called soft systems management. SSM has a focus in social situations that are always complex due to multiple interactions between different elements in a problematical situation as a whole, and systems ideas are fundamentally concerned with the interactions between parts of a whole (Checkland & Poulter 2006, 4). The also talk about system idea. They concern interaction between parts which make up a whole and the core systems idea is the system to survive through time by being adaptive to changes of the environment.

So in comparison soft systems thinking is more about organizational design, information systems, understanding complex situations and mics things like business strategy and risk management. It also frames the problems not to be easily defined or easily quantified. Hard systems approach is more science based and it assumes that systems can be well-defined and they have a optimum solution – with a data driven attitude.

As D. Meadows states “The universe is messy. It is nonlinear, turbulent, and chaotic. It is dynamic. It spends its time in transient behavior on its way to somewhere else, not in mathematically neat equilibria. It self-organizes and evolves. It creates diversity, not uniformity. That’s what makes the world interesting, that’s what makes it beautiful, and that’s what makes it work.”

How to apply systems thinking in the government context?

We started drafting our systems model by drawing a stakeholder map with the flows of money, information and material. We started marking intervention points based on the twelve leverage points Meadows reluctantly suggested in the aforementioned book. . “I offer this list to you with much humility and wanting to leave room for its evolution”, she remarks.

To truly understand a system behavior you should observe it over time. Feedback loops often have long delays, which is why the true nature of the system and problem cycles might not be immediately obvious. This is of course a challenge for decision-makers with limited resources available. Systems thinking helps to understand how a system currently functions and make an action plan through leverage points, the potential intervention points in a system.

We discussed that systems thinking could be an useful way of thinking for those who are tackling complex issues. We as designers can see systems thinking as a method of making models and consider them as a mode to inquire and ideate. For managers, it might help their planning activities with long-term perspectives.

We’ve found systems thinking very useful in making sense of the context of SFVS. The number of stakeholders involved in the scheme is enormous, and how they are connected with different goals, incentives, and values is complex. Mapping out their communication, collaboration and power relations has been essential in understanding potential points of intervention. We have learned that the amount money in SFVS is not very big relative to the price of vegetables, which is why it is important for us to find the most effective way to use it.

We think that part of the reason why the scheme has not been implemented yet is that it is difficult to find common understanding, goals and approaches between the different stakeholders. They are generally very positive towards the SFVS and would like to see it happen, but the leading motivations to participate in and fund and work for the scheme are quite different for different stakeholders. We are still in the process of mapping these motivations out based on the interviews we’ve done, but we are confident that the systems approach will help us find the important nodes of common motivations that we can use as leverage points to enable collaboration within the network of stakeholders.

But as Donella H. Meadows points out, systems can nevertheless still surprise us.