Editor’s note: We offered this blog as a platform to the DfG course participants who are documenting the DfG course for readers to get a glimpse of how things went. This is one such post by Primary Producer’s Notification team 1.

The previous post on the DfG blog took a look at the beginning of the course – the Orientation Block. Now we offer a recap of the second block, which was all about empathy and how to apply it in the design process. We’ve been trying to understand the primary producer’s point of view on the notification process, and therefore this post begins by discussing the empathic design process and concludes by exploring the insights gained from applying it in the context of our project – Primary Producer’s Notification.

What is empathy?

To understand empathic design, we must first understand empathy. The dictionary defines empathy as “the feeling that you understand and share another person’s experiences and emotions”. Juha, the responsible teacher for this block contrasted this with sympathy: whilst sympathy can be just compassion towards a person, empathy requires a deeper connection. It’s about being able to put yourself in someone else’s shoes and understand them through their perspective, through their experiences.

What is the role of Empathy in the Design Process?

Empathy offers a practical way of approaching design because it puts emphasis on the experience of the end user. Any designed artifact – be it a bus stop, public service, regulation or legislation should take into account the needs and wants of the users as a primary principle. The empathic designer understands that people rarely know themselves what they actually need (or sometimes even what they want before they see the proposal.) Therefore the designer does not always ask the user directly about the issue at hand – instead insights are collected using a number of different methods to create holistic and multileveled understanding.

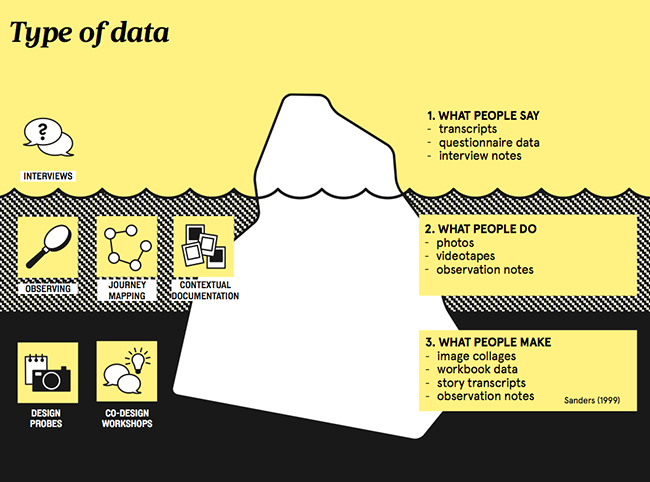

“The Iceberg” is a commonly used metaphor to help us understand different levels of knowledge that can be uncovered. The tip of the iceberg is used to represent the most superficial level of knowledge; this is an overview of the situation which can be revealed during interview. This does not mean that information gleaned from interviews would not be valid, but we can only gain knowledge about what the interviewee wishes to talk about without much filtering or reflection. There could be information the interviewee may not wish to reveal, opinions or ideas they may be embarrassed to admit or aspects that don’t occur to them immediately. Just under the surface lies information that we can notice using ethnographic observation. This could include observing interviewee body language, to try and understand how they feel about what they are saying or the situation at hand. This has been the staple of an ethnographic researchers toolkit for a long time, and it has become a popular method for designers to gain insights into users as well.

However, the deepest, most elusive insights might also be valuable. These include people’s dreams or desires they may not realise they have, and thoughts they may not be able to consider relevant. There are many ways of gaining access to these insights with design probes or games being the most common. The iceberg model makes it appear that there’s a clear division between these levels of insight. However, the reality is that thorough empathetic design requires the designer to interpret the differing levels of insight and how they are connected. All methods are valuable but there should be a clear purpose as to how and why they are used.

Research and Method Planning

This is where the real task of the empathy block comes in – to explore research methods and generate a research plan for the project. To achieve this we analysed data from the Atlas workshop and the first few stakeholder interviews using affinity diagrams and rapid personas. Analysis is important because if one simply has data, it’s not very useful – it must be refined into information, then into knowledge and wisdom. Through this analytical process we are able to form a big picture of the problem at hand. If we are lacking the big picture provided by knowledge and rely on pure data, it may result in focusing on irrelevant problems.

The research plan required the teams to consider their original brief and highlight key questions for future research. The goal of the plan is to encourage the teams to reflect upon which issues are the most important. Then we can understand which design methods and tools are most appropriate to find relevant insights. Each method helps the team analyse a different aspect of the questions they want to answer, or different parts of the aforementioned “iceberg”. Methods such as the design probe would be used to dig deeper into the overarching motivations and dreams of stakeholders involved. A probe can take the form of a reflective diary, a camera or recording device, a collection of contextual drawings or objects which help the designer get to this elusive, bottom level of the iceberg.

A Primary Producer’s Perspective

Before deep, empathy tools such as the design probe are used, we began to build a contextual knowledge base through interviews with stakeholders – one of the most memorable being our first trip to a farm.

To gain understanding into how the notification procedures are seen from a primary producer’s perspective, we packed our bags and drove to Kirkkonummi to visit the farm of a rather famous Finnish businessman. There we met the caretakers of the farm and had our first glimpse into life through the eyes of a producer running a farm.

Coming from a distinctly outside perspective, it’s difficult to get a grasp on how the actual user experiences the system. The caretaker of the farm, Paavo, explained to us the need for diligence with the paperwork – a single delayed notification to the animal database can cost the farmer the price of a few trucks in decreased subsidies.

Paavo was transparent about the agricultural subsidies system, noting how farming in Finland would not be possible without this support. This made it clear to us how empathy and systems can connect; it’s impossible to gain insight on how a system really works without understanding the users of that system. We discovered the primary producers’ living is even more intertwined with the whole EU-level programmes than any of us had imagined.

Touring the Farm

In addition to the interview, we were given a short tour of the farm. It was a big farm which mainly focused was on organically produced, quality meat. This seemed evident in the surroundings, with the animals being well taken care of. At the same time, it also reminds us about the potential obstacles of observations and interviews. Producers with animal welfare as their primary goal may have more incentive to show their property to visitors, whereas we may have limited access if a farm keeps animals in poor conditions.

Key Takeaways

To conclude; whilst doing interviews one needs to keep in mind the context of what is shown, overcome one’s own assumptions and keep in mind that insights gained may be biased and not suitable for generalisation. That’s why a project dealing with systems, complexity and many stakeholders needs a lot of data and empathic understanding, so that the end result doesn’t end up being biased towards one perspective.