This blog post reports on work-in-progress within the Design for Government (DfG) course! The post is written by students addressing the project brief ‘Boosting climate education’ provided by the Ministry of Environment (YM) in collaboration with the Ministry of Education and Culture (OKM), the Finnish National Agency for Education (OPH) and the ORSI research consortium. The group includes Rinna Saramäki, Zhengshuang Han, Noah Peysson and Jelske Van de Ven.

After the stakeholder workshop that was collaboratively organized in the second week of DfG (previous blog), we decided to deepen our understanding by learning from the experts dealing with the topic of climate education on different levels. We organised and carried out a total of 11 interviews with professionals, including ministry employees, researchers, headmasters, and teachers. The information from these interviews was analysed by identifying common patterns and themes. These different angles helped us to make sense of the complexity surrounding climate education. In the mid-term presentation, held on 31.3.2020, we highlighted four of our main insights. In this blog, you can read about these.

No consistent view on Climate Education among stakeholders

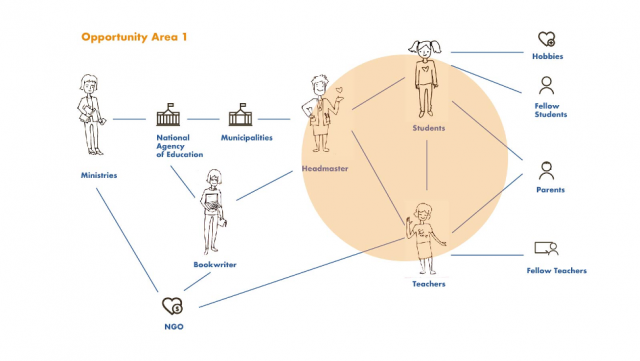

In every interview, we were presented with a different perspective towards climate education or new terms used to what seemed to describe the same idea. We discovered how some people view climate education as teaching students to become conscious consumers, looking critically at their own behaviour. Meanwhile, others focus more on active citizenship, letting students experience what they can do to change society. Because of this inconsistent perspective, a multiplicity of problems emerges. One of them is that official teaching materials such as schoolbooks do not cover topics on active citizenship and that teachers have to find their materials online.

“In climate education, the main goal is how to learn how to consume less. How to be happy without only consuming, how to enjoy nature. The idea is less is more.” – Schoolbook writer

“Climate education is learning how democracy works.”– Climate education trainer

Teachers need peer support and a diverse network

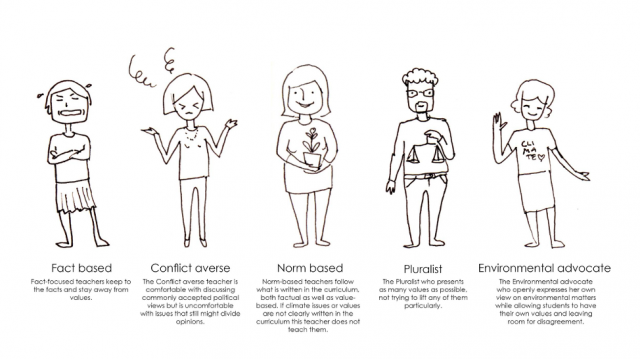

Climate education researcher Essi Aarnio-Linnanvuori has discovered five different responses by teachers to teaching the value-laden and active citizenship side of climate education.

The first three types (at left) have difficulty in engaging in political or values discussion in class, whereas two teacher types (at right) side feel more comfortable with teaching active citizenship. We found that these latter types of teachers typically has a diverse group of colleagues with whom they share ideas in the breaks. This helps these teachers to have a more holistic perspective on the topic and more confidence in answering students’ questions. Also, in schools where the teachers receive peer support in bringing up political topics, they feel more secure in teaching active citizenship.

“Teachers that have a multidisciplinary coffee room team are more confident about climate education” – Climate education researcher

Holistic climate education on school and policy level

While everyone agreed a holistic approach was needed, our third insight is that the current structure may not support this. With climate education usually taught in biology and geography courses only, both teachers and students struggle to link the information to broader topics. Additionally, if the school environment is in line with climate education values, students take it more seriously.

“It is a weakness to split the subjects, as teachers end up seldom talking to one another.” – Headmaster of a secondary school

“We have for example led lights that go off automatically. Heating systems are clever so it does not heat when school is empty. All the water goes on and off automatically.” – Headmaster of a leading climate education school

When learning more about the ministries’ approach to education, we found little hints that education on a policy level is not approached holistically. Instead, it seemed siloed in different departments. This is a hypothesis, and thus we are curious to explore if this is really the case and what the possible consequences are of this siloing on the ground.

Open dialogue in school about the format of participation in climate activism

Our research pointed out the fact that, in many schools, an open dialogue on the different forms and levels of participation between students, teachers, and headmasters wasn’t taking place. To answer this need, we will organize in the coming weeks an online workshop with all three types of stakeholders to reflect on the current problems and ideate on how to approach the future of climate education.

Next steps: ideating towards a solution

We received feedback from the mid-review to narrow down our scope. The next weeks will be spent on deciding which angle is the most fruitful in creating change and empowering individuals to boost climate education. We will then work towards creating solutions.

The DfG course runs for 14 weeks each spring – the 2020 course has now started and runs from 25 Feb to 19 May. It’s an advanced studio course in which students work in multidisciplinary teams to address project briefs commissioned by governmental ministries in Finland. The course proceeds through the spring as a series of teaching modules in which various research and design methods are applied to addressing the project briefs. Blog posts are written by student groups, in which they share news, experiences, and insights from within the course activities and their project development. More information here about the DfG 2020 project briefs. Hold the date for the public finale 09:00-12:00 on Tuesday 19 May!