This blog post reports on work-in-progress within the Design for Government (DfG) course! The post is written by one of the groups dealing with the project brief ‘Boosting climate education’ provided by the Ministry of Environment (YM) in collaboration with the Ministry of Education and Culture, the Finnish National Agency for Education (OPH) and the ORSI research project. The group includes Aman Asif, Maddalena Galloni, Suvi Majander and Emma van Dormalen.

Finland is aiming to be carbon neutral by 2035 and finding new ways to achieve this is paramount. Finland is known for its good quality of education, therefore using it as an instrument for change seems like an obvious choice. Our project aims to find new directions to boost climate education and help the Finnish school system to raise the next generation of proactive, climate-conscious citizens.

Working with a broad brief meant that we had to define our own scope for improving climate education. After conducting a workshop with a few people that are involved in the Finnish of climate education scene, we had questions that guided our research. What is active citizenship? What is climate education? What does the current Finnish education structure look like? And what does this mean for the various stakeholders such as civil servants, experts, and teachers?

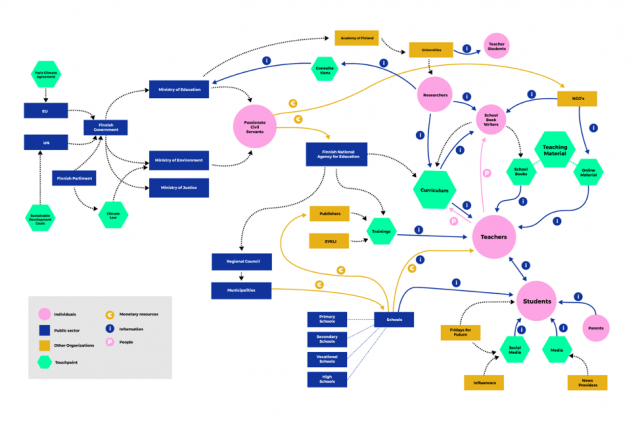

We began to make sense of this complex situation by mapping out who are the different organizations and individuals involved in climate education, in terms of their roles and kinds of interaction that takes place between them e.g. the flow of information, monetary exchanges, and collaboration. Based on the actors identified in the map, we planned out our interviews to get their perspective on climate education. As you can see a lot of the arrows connect to the teachers, hence at this point our focus was towards them.

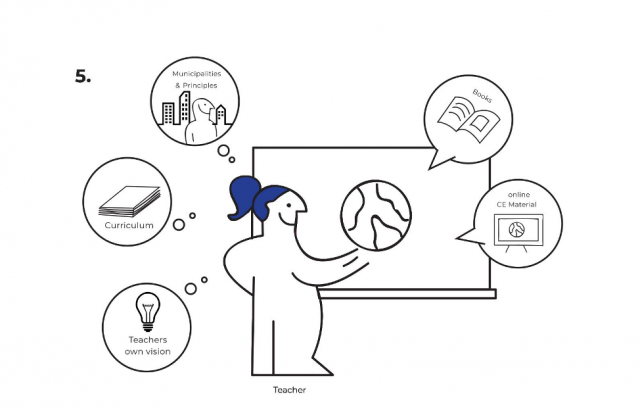

Based on interviews, some of the aspects the teachers take into account are; the different values included in the curriculum, municipalities’ vision, school culture and, of course, their own beliefs and interests. Most of the teachers that we talked to mentioned that there were enough materials on climate education available for them however the challenges lie in the overflow of information available and difficult to verify or manage it. This can make it overwhelming for some teachers, hence those that have high levels of motivation and a personal interest towards climate education are more likely to incorporate it in their teaching.

From our research, we gained a wider understanding of the current state of climate education in Finland. One of the insights we obtained was that since teachers have a lot of autonomy in Finland, it is quite a challenge for policymakers to know what actually is going on in the classrooms. The teachers have the freedom and space to implement and interpret climate education guidelines that have been set by the government. Even though the work is being done on climate education at the teachers’ level there is ambiguity for the government as there is no clear way to measure or monitor the government goals in regards to raising more climate-aware citizens.

Another source of ambiguity comes from the fact that both climate education and the Finnish curriculum are based on values. This makes it hard to have a universal measurement strategy that would tell how effective is the current way of teaching about climate change and active citizenship. It comes down to the individual teachers, schools, and municipalities involved in how they interpret the values presented to them and then apply these values to their own work. We found that the teacher is the last link to this process of decoding the given values, thus making them the final gatekeeper of climate education.

Next, we plan to talk to those who truly are one most essential pieces of this multi-dimensional puzzle of climate education – the students. While diving into the brief, the perspective of the youth has been basically absent. In order to find ways to educate the youth, we have to understand their world and emotions. What are the channels for them to participate and voice their opinion about climate policies and how much do they actually know about them? How could we use this information to help Finnish teachers to become the best climate educators in the world?

The DfG course runs for 14 weeks each spring – the 2020 course has now started and runs from 25 Feb to 19 May. It’s an advanced studio course in which students work in multidisciplinary teams to address project briefs commissioned by governmental ministries in Finland. The course proceeds through the spring as a series of teaching modules in which various research and design methods are applied to addressing the project briefs. Blog posts are written by student groups, in which they share news, experiences and insights from within the course activities and their project development. More information here about the DfG 2020 project briefs. Hold the date for the public finale 09:00-12:00 on Tuesday 19 May!